Horace Dade Ashton began exploring the world as a teenage cabin boy in the late nineteenth century. His love of the sea and the open ocean led him to explore many parts of the world when travel was difficult. He wrote about his travels, and I’m delighted to present excerpts from them to fellow adventurers.

by Libby J. Atwater, coauthor of The Spirit of Villarosa and author of a What Lies Within

HAITI

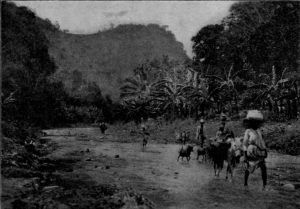

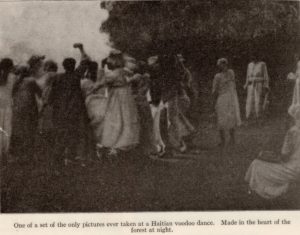

Intrigued by what anthropologist Levy Bruhl had told him about Haiti, Horace Ashton yearned to visit the exotic island. His opportunity came in 1906—after he photographed President Theodore Roosevelt digging the Panama Canal—when he sailed to Santo Domingo, the country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. In Santo Domingo he met an Episcopal bishop who was embarking on a horseback trip to Haiti and agreed to let Ashton join him.

Horace recalls his first encounter with Haiti vividly. “My anticipation built as we rode across this beautiful tropical island, enjoying its majestic mountains, lush greenery, fragrant flowers, and bright sunshine. On the final day of our journey we mounted our horses and rode across the Haitian border at Fond Parisien, near Gantier. Having been on many spiritual journeys, I sensed there was something special about this place. I could feel it. The air felt more alive, or perhaps it was the perfume of the flowers or the vibrant colors of their display on our path as we rode. The climate, although hot, wasn’t oppressive but electric with promise . . . or was it I who felt such sparks? I breathed deeply and closed my eyes for a brief moment. I opened them to find an old man had suddenly appeared in the road, holding up his hand to stop us. He took hold of my bridle and said, ‘Welcome, Mr. Ashton. I have been sent to meet you.’”

From the moment he entered Haiti on horseback in 1906, Horace Dade Ashton fell in love with the land and its people. Little did he realize that he would spend that last 30 years of his life in this tropical paradise.

FRANCE

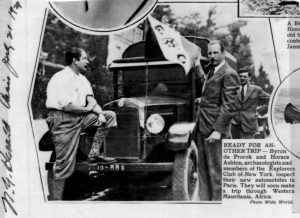

In the late 1920s Horace Ashton and his dog Roscoe sailed to France to lead the first European automobile caravan. Ashton describes the French countryside and his loyal canine companion in his own words.

“When the Ile de France docked in Le Havre, the cars were hoisted onto the pier, where French license plates were attached. I debarked, along with forty-six other Americans bound for the caravan, and we met the representative of the Automobile Club of France….

“The next morning, I led the caravan to Paris with Roscoe perched on the passenger seat wagging his tail. We drove the first fifty-two kilometers in a northeasterly direction, passing through the pretty little towns of St. Romain and Bolbec to Yvetot. We then turned southeast into the Seine Valley, through beautiful, rolling, emerald-green farm country to Rouen.

“It was July, and our trip was blessed with good weather. As we drove through Normandy, we observed quaint farmhouses, peaceful sloping fields, and long rows of fat, contented cows tethered near patches of red clover. Snowy mountains of cumulus clouds floated in the turquoise sky above as the route south from Rouen to Paris followed the lovely Seine River, taking us through the towns of Vernon and Nantes. Sometimes the road ran on top of hills, from where we could see miles of blue ribbon winding like a serpent through the valley below, and at other times we viewed the river more intimately from along its tree-bordered banks, listening to the whistles of boat traffic….

“We entered the City of Light via Avenue de la Grande Armée, and both sides were lined with the booths and decorations of a great street carnival. We passed around the Arc de Triomphe and down the Champs-Elysées to our hotel, where I made final arrangements for the extensive road trip of which I had long dreamed.

“The ramble through France was everything I’d hoped for and more; for me, it was the fulfillment of a number of dreams. I drove through Brittany with its medieval chateaux, its straw-thatched cottages made of stone, its black-dressed, lace-bonneted women with smiling eyes, and its men in blue smocks wearing little round velvet hats with long streamers and wooden shoes on their feet. I visited Mont St. Michel, that curious, picturesque group of buildings surrounded by a wall and topped off by a lofty cathedral spire that appeared to be afloat in the dim evening light, like a painting on a blue gauze curtain. I spent the night close to the sea in St. Malo, where a profusion of red, pink, and white roses bloomed against the gray stone walls of the thatched cottages and the intensity of their perfume drowned out the smells of seaweed and salt mist.

“Sunday morning dawned bright as I drove south to Concarneau through the music of pealing church bells. On the way I passed numerous two-wheeled carts on which peasant girls—dressed alike in black velvet with tightfitting bodices and full skirts, white lace collars, and the daintiest of white lace caps—were seated three abreast, heading to church. Not unlike other Christian communities I had seen, there were twice as many women as men among the church-goers.

“The most striking feature of motoring through France, which made it most enjoyable, was the absence of traffic upon the roads. There were hundreds of miles of marvelous roads through beautiful country and no motorcycle cops!”

Can you imagine making this same trip today?

THE SAHARA DESERT

Horace Dade Ashton made several journeys into the Sahara Desert and North Africa. Today we might call these “business trips,” but in the 1920s they were adventures. Ashton described his trips and the peace the Sahara brought him.

“My first intimate journey into the Sahara began at Biskra, an Algerian city bordering the eastern side of the desert. . . . I was hired to make a series of films of a genuine sandstorm, something that had never been attempted.

“Before I left the United States, I’d had a special camera constructed to keep out the sand. At Biskra I paid an exorbitant price for a camel caravan and local tribesmen willing to venture into the desert during sandstorm season. Our caravan headed southeast for several days into the

Eastern Erg, where the sand dunes were sometimes six or seven hundred feet high. Despite the hardships of riding on a camel in the hot sun and blowing sand, I was instantly won over by the charm of the desert.

“On the one hand, the power of the desert presented great risk, but on the other, it offered the most blessed peace I’ve ever experienced. Caravan life was basic, focused on survival. Every day our drinking water would be almost boiling hot by the time the sun set, and every night we’d wrap the water jug in a woolen blanket covered by a wet goat skin to cool it.

“As I drifted off to sleep, the occasional groaning of the camels after they had traveled long distances without grazing was the only sound I heard. This—my first experience sleeping in an Arab tent in the open desert—was the beginning of my love affair with the Sahara, whose lure, like a siren’s song, would repeatedly call me back….

“I’ve often wished I were a poet so I could do justice to those desert nights. The surge of emotion I felt each evening as I watched the sun slide quickly under the distant line of sand, leaving a vermillion-hued trail, was my reward; I had survived another day in the desert to experience the cool, life-saving silence of its night air….”

SPAIN

Horace Ashton’s decade as a lecturer/explorer really began when the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique hired him to create motion pictures that would bring American tourists to Morocco and Tunisia in 1920.

At the time flight was not yet an option for international travel, so Ashton departed New York Harbor on a ship bound for Spain. From there, he planned to travel by car and train to southern Italy, where he would board another ship for North Africa. He had not counted on having car trouble.

After having two flat tires while driving an open Buick from Barcelona to Madrid, Ashton was rescued by another motorist and his chauffeur. His Good Samaritan turned out to be King Alfonso of Spain, who invited Ashton to return to Madrid with him, while the chauffeur remained behind with Ashton’s car. While staying at the palace, the young filmmaker met the king’s cousin “Jimmy,” the Duke de Alba, who became a lifelong friend.

The people and the Spanish countryside evoked enduring memories that Horace described. “At the time, Spain affected me deeply…. As I traveled through Andalusia, heard its native music, breathed its perfumed air, and studied its colorful and ravishing Moorish architecture, the country awakened memories in me that reinforced my belief in reincarnation. I would later trace these memories to events in the march of Hannibal’s invading forces that had crossed from Carthage in Africa to Europe at the ‘Pillars of Hercules,’ now Gibraltar. In this other life, I became convinced that I had apparently headed eastward with them across Europe toward the ill-fated siege of Rome.”

Ashton later proved his theory of Hannibal’s march, but that’s a story for another day.

Leave a Reply