Then, at a monthly meeting of the CCA, the main event was a home-made film of members who had canoed the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. As the screen flickered, a spell was cast. I was mesmerized: the waves seemed oceanic, ten times the size of anything I’d encountered on the Cheat or the Rappahannock, even in spring spate; the scale of everything crushed my mind—the canyon walls, the crests and troughs, the eddies, the wet grins. Some invisible, powerful hand reached from the screen and pulled me in like no $100 million movie ever had. I drove home with a monomaniacal craving: I had to run the Colorado, or die.

With no guiding background whatsoever, I composed a letter to the company that had outfitted the CCA, Hatch River Expeditions, and asked for a job, lying through my teeth about my vast experience. I had never rowed the Green; had never traveled west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. But, something of my passion must have leaked through, as Ted Hatch, the owner, wrote me back: “Report to Lee’s Ferry April 28 for trip departing April 29. Welcome aboard.”

The flight into Page, Arizona, over the southern rim of the Colorado Plateau, across the brilliantly cross-bedded deposits of Navajo Sandstone that coat the escarpment, was gorgeous. I’d never seen such a vast expanse of uninhibited land, devoid of almost any sign of human presence. In the soft, coral flush of daybreak, I pressed my nose against the window in utter awe. Then, like a gash in the skin of the desert, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado appeared, a dark, crooked rip tearing across the landscape to the horizon.

My first job was to drive a winch-truck down to Lee’s Ferry from Page, Arizona, near the airport. It wasn’t easy for someone who had never used a clutch before, but despite a crushing conflict with the hanging plastic sign above the driveway of the Page Boy Motel, the trip was a success. I clutched and double-clutched the 50-mile route, crossed the 467-foot-high Navajo Bridge, and wheeled down the ramp at Lee’s Ferry.

My unwell-earned advice for Colorado River water (with help from TravelSmith)

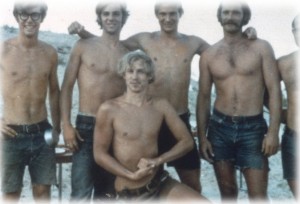

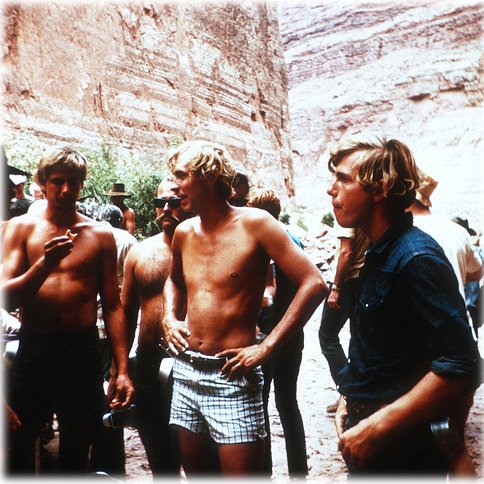

A line of 33-foot-long World War II surplus pontoon bridges, refitted as passenger-carrying rafts, were being inflated by gasoline generators. Stepping out into the dry, 95-degree heat, I faced my colleagues to be, and for the first time encountered river guides. Ten of them. Bronzed beyond belief, muscles like a Rodin sculpture, hair thick and bleached by the desert sun, Skoal stains on their chins. One sported a tattoo, a fly chasing a spider. Everyone seemed several inches taller than my 6’1” frame, and at least 20 pounds heavier—all gristle and sinew. As I made the rounds of introductions, I felt as out of place as a white-tailed deer in a pen of mountain lions. What was I doing here? If I’m fired, I thought, I’ll hitch to Vegas and find a job as a bellboy.

I’d never met anyone like these people. Exuding lava flows of confidence, fitter than any lifeguard, they went about their tasks with pure confidence and blithe indifference. Not a one spoke with the enforced sense of grammar and syntax that had filled my upbringing. All were from the West, and a different culture prevailed. Here, style, smile and tan made nobility.

I was assigned the cook boat, piloted by 26-year-old Dave Bledsoe, a black-headed bear of a boy, son of a Lake Mead marina manager. Sharing the raft with me was Rick Petrillo and trainee Jim Ernst. Our job was to precede the ten-raft armada to each camp and set up the commodes and kitchen. Each morning, after our passengers from the Four Corners Geological Society departed, we would remain behind to clean camp and bury the mountain of trash and excrement that 110 geologists, 10 boatmen, 10 assistants, 4 trainees and 1 swamper (me) had left behind.

As we launched into the swirl of green that is today’s Colorado—the silt that led Spanish explorers to name it “red colored” now settles out in the reservoir 15 miles upstream behind Glen Canyon Dam—I was grabbed by a view as absurdly otherworldly to me as that of another planet. Mesas, side canyons, bosses, ramparts, benches, monoclines, and faults all shared the intimidating landscape. This was the place I wanted to be. I went into high gear, playing vassal to river guide Dave, and saw the Canyon in all its glory. In turn, Dave showed me the ropes, literally, from half-hitches to the layered rock history. His syllabus was the open textbook of 1.7 billion years of exposed geology, more than a third of the earth’s 4.6 billion year age. His lectures were filled with tales of crusty hermits and florid raconteurs, of the gold-miners’ greed and the romantics’ bitter comeuppance.

Within the depth of this holy gash, as the rapids came one after another and the space between the walls narrowed, I soon learned that river guides were moved to create a myth or two.

I witnessed and was part of an odd transformation that took place that summer. Ordinary people—many college dropouts, ski bums and ranchers’ sons from the hard-scrabble patches of Utah, New Mexico and Arizona—became extraordinary on the river. They turned into men who faced danger with chests and chins thrust forward, with a smug curl of a smile under any circumstance or crisis. People who were a bit soft or insecure around the house turned gneiss-hard on the Colorado, resolute souls who held together when Ivy League lawyers, doctors and corporate CEOs panicked. They were men who lured wives away, if only for a fortnight, with the arch of an eyebrow; men who lived by wits and wile and animal resourcefulness in a Spartan way: with a pair of sun-faded shorts, a Buck knife, a sleeping bag, a bottle of Jim Beam, and a pair of pliers.

The subjects of these myths—and their perpetuators—are the boatmen themselves. Most river guides are quick to capitalize on their center stage position: they sing off-key before appreciative audiences, they tell bad jokes that send laughter reverberating between the Supai sandstone walls; they play rudimentary recorder as passengers sway revival style. Most of all, though, every guide takes advantages of the rapids—all 161 of them. Those white knots in the river’s long, emerald ribbon are chances to shine, to polish the legend of the dauntless river guide.

As big and visually impressive as the Colorado rapids appear, they are, by most measures, relatively safe. If a raft flips, wraps, broaches, jackknifes, tube-stands, noses under, or all of the above, the entire crew could swim the rapid from tongue to tail waves and everyone would almost certainly emerge intact in the quiet water below. But the boatman seldom admits to the rapids’ general forgiveness. That’s a secret.

The script calls for high drama at each cataract, and the river guide knows how to milk the scene dry: “Hold on tight. The next one’s a killer.”

All this theater reaches its climax at Mile 179—Lava Falls. Formed of flows from eruptions within the last million years, it was named by John Wesley Powell upon his arrival at its chapped lip on August 25, 1869. He was the first boatman to wax dramaturgically about the volcanic intrusion. “What a conflict of water and fire there must have been here! Just imagine a river of molten rock running down into a river of melting snow. What a seething and boiling of the waters: what clouds of steam rolled into the heavens!”

Rimmed with black, burnished rock, chopped into a mess of crosscurrents and nasty sharp holes, the rapid drops 37 feet in 100 yards. It has been clocked at 35 miles-per-hour, claiming title as fastest navigable water in America. Statistics notwithstanding, Lava Falls strikes terror in the hearts of first-timers—swampers and boatmen included. It appears so angry, confused and huge, with no evident passage, that the initial urge is to look for a hidden staircase out of the canyon or a bush to crouch behind. It is all quite deceptive, nonetheless. Wherever a boat enters this thundering, fuming, spitting monument to chaos, the chances are better than even it will issue upright at the bottom. If a boat flips—and many do—the passengers have the swim of their lives. But they bob out okay, unscathed, almost every time.

For the river guide, however, the performance begins days upstream with a casual campfire mention of the upcoming conflagration. The anecdotes build over guacamole salad, with tales of near-disasters, party to or witnessed. Then one day it dominates the conversation over breakfast, building to a crescendo as the boats float downstream to Vulcan’s Anvil. This basaltic neck, the core of an ancient volcano, now sits mid-river one mile above Lava Falls—looking, some boatman say, like a 40-foot-high tombstone. From this point a respective silence descends, and the boats drift closer to the low, guttural groan of Lava.

The boatman’s danse macabre begins at Lava’s lip. The boats are beached, and the guides climb to the sacred vantage, a basalt boulder some 50 feet above the cataract. Once there, weight shifts from heel to heel, fingers point, heads shake, and faces fall. This is high drama, serious stuff—the white stuff….and passengers eat it up. This is the reason people spend good money to sleep on hard ground, eat stew mixed with sand, and go where they find no hot running water and no flush toilets: quite simply, they get scared in a safe, spectacular setting. Lava gives everyone his money’s worth, and then some.

After the scout, which can take half a day, the boatmen, somber as pallbearers, return to their rafts to check riggings, remind passengers of emergency flip procedures, then launch, one by one, into the maelstrom. Lining up is the key to a “clean run,” one that doesn’t flip and loses no passengers or gear. Once in the fist of Lava, there is no control—just hanging on as it shakes its intruders like hot dice.

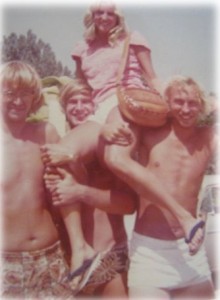

Then, of course, after crashing through hell itself, staring into the pits of flaring holes, and then purling into the eddy below, the passengers erupt into applause and praise, as though a divine hand has just delivered them from an eternity on the River Styx. At that dizzy instant a river guide can’t help but beam.

On my third Canyon traverse I was allowed to man the 12-foot wooden oars at Lava, though I could barely lift them. Dave Bledsoe sat behind me on the captain’s bridge, and bellowed command over the pandemonium: “Right oar. No. Left. Now both. Harder!” In the eye of this typhoon, I tried to follow orders, but it seemed to me I had barely executed a few inches of a right-oar pull when Bledsoe was clamoring for the other. Nevertheless, when we made the landing, amidst the ovation and backslapping from our passengers, I turned to Dave and asked the all-important question, “How’d I do?”

Dave pulled a bottle of champagne from his ammo box, shook it violently, and popped the cork so it shot across the river and into the white spinning skein of Lava’s last wave. It was Big Top performance material. And I learned to play it with three-ring stagecraft.

Below Lava Falls the boatmen are bathed in a powerful limelight, washed in post-navigation euphoria. That night the guides are treated as though they’d hit the winning run, bottom of the ninth, at The World Series. After days of boating through the Canyon, with no contact with the outside, the universe has been reduced to the party at hand, and this universe claims these guides as Olympus-dwelling gods, charged with divine courage and skill.

But even in the midst of all this mythology and pedestal placing we were not infrequently hurled to earth. After one trip I took to bed in a Flagstaff motel for three days, curled in a feverish ball. At last a fellow guide drove me to the hospital, where the doctor took a stool sample and gave me a dosage of Flagyl. Within the day I felt good enough to join the next trip. But then half-way down the river, during a lunch break on a thin beach, a helicopter swooped into view and signaled for us to turn on our radio. The pilot said he couldn’t land because of the narrowness of the gorge, and then asked if Richard Bangs was in the group. When Dave Bledsoe affirmed, the pilot said I had to be quarantined…that a stool sample showed that I was ringing with Giardia lamblia, a parasite picked up by drinking unfiltered Colorado River water. I was directed to avoid contact, as much as possible, with the other rafters until the end of the trip, still a week away. The upside: I never really enjoyed kitchen duty, and I had to stay away from those chores, and meals were in turn brought to me on a tray, like room service.The Long and Short of it[/caption]One common current, though, runs though all who have drifted into the life of a Colorado River guide—the moment when all the universe is reduced to a cool, wrapping white surge, when with the pull of an oar, or the twist of a tiller, the wave is crested, the top of the world is reached, and for a magical instance, all is good and great.

Returning to college I found it difficult to adjust. While I had freshly been in a whirlpool of activity in one of the most sublime settings on the planet, I was now cloistered in pale library walls, lost among thousands of milling students, buried in books and papers. The Colorado never left me, not for a waking instant. At every opportunity I launched into long-winded descriptions of how I had spent my summer vacation. As one who has thoroughly learned a new language, I now thought in Grand Canyonese. I fancied myself a river guide…that was now the axis upon which my identity now turned.

I couldn’t understand why the world outside the canyon didn’t appreciate my talents. Just weeks before I was being praised by kings, America’s royalty sought my council, and all heralded my accomplishments with loud cheer. At school nobody noticed. My tan quickly faded, my stomach bulged a bit, and I sank into anonymity. When a professor handed back a paper with a low mark, I wanted to stand and yell, “Hey, you can’t do that. I’m a Grand Canyon river guide!”

And, so, after college, I came back to the Colorado, and then rivers throughout the West, and then around the world and in some fashion, I have been a river guide ever since.

Looks like quite an incredible experience.