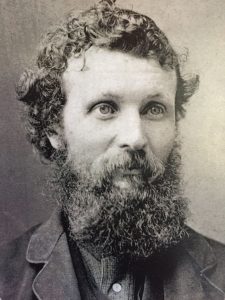

The best place to walk in the footsteps of John Muir is Yosemite National Park, where the famed naturalist and conservationist hiked and climbed granite domes, lovingly surveyed plants and animals, studied with rapt eyes “cloud mountains” in the sky, and developed his passion for wild spaces.

Another place that evokes feelings for one of the visionary creators of our national park system is his old home in Martinez, California, about an hour and a half east of San Francisco. The four-story Italianate-style house, built in the early 1880s, is a National Historic Site open seven days except for holidays and free to the public.

A Different Side of Muir

The house explores a less known aspect of Muir’s life: his domestic side. His wife, Louisa “Louie” Strentzel, was the daughter of a wealthy doctor and horticulturist. They married and moved into what is now known as the Muir-Strentzel Estate. Not just a child of nature but also an adept businessman, Muir, a Scotsman by birth who knew farming from his days as a boy in Wisconsin, threw himself into fruit ranching. When he died, in 1914, his fortune in today’s dollars would be valued in the millions. But his heart was always in the mountains, and Louisa encouraged him to write about his younger life when he was exploring the grand rock cathedrals of the High Sierra.

His Meaningful Scribbles

As influential as his writing was, and still is, Muir, like all writers, despaired that all his scribbles meant nothing. “No amount of word making will ever make a single soul to ‘know’ these mountains,” he wrote in a journal passage that is on display. “One day’s exposure to mountains is better than a carload of books.”

Carefully Preserved Past

Including his scribble room, the living areas, bedrooms, and artifacts of the house are carefully and thoughtfully preserved in keeping with the time in which John, Louie, and their two daughters lived there. Telephone service came to the estate in 1884, and there’s an old wall phone dating from around that era. A highlight for me was a trip to the top of the house to ring the bell in the bell tower. The third floor attic features a display by the Sierra Club, which Muir founded. From there climb a narrow stairway of 18 steps up to the airy, sunlight-filled wooden structure.A hundred years ago Alhambra Valley consisted of ranchlands and orchards far away from the madding crowd of the cities. Now a freeway rumbling with traffic runs next to the estate, and a gas station occupies the corner across from the entrance and parking lot. This last may be an especially painful irony, given how much Muir despised the coughing, sputtering, backfiring horseless carriages of his day. He much preferred to walk.

Staying Faithful to its Past

The federal custodians of the site do their best to maintain the aura of a bucolic preserve faithful to its fruit and vegetable heritage. There are small stands of pear, olive, apricot, and quince trees, and a cluster of grapevines. A sequoia tree on the grounds planted by Muir himself stands some 60 or 70 feet high—“a venerable, impressive old monument of a tree,” to quote the man on another sequoia he once saw.

At the rear of the estate is a 19th century Mexican adobe featuring a display on the early exploration of California by the Spanish military officer Juan Bautista de Anza. There are picnic tables and ample room to run for children who, like the young Muir, have too much restless energy to stay indoors long. A cellphone audio tour is available. Another highlight can be found in the gift shop. There is a statue of the great man that is perfect for all his admirers, both young and old, who wish to have their picture taken with him.

Leave a Reply