It feels like we’re driving to the edge of the world where the water falls off.

Infinity is just ahead. To the right are mountains that arc up from the basement of time. On the left, a dry lakebed now glassed with salt. This is the driest state in the country, not so surprising, but it is also the most mountainous, with some 300 ranges.

If you look at a satellite photo of earth at night one of the brightest pixels is Las Vegas in southern Nevada. But, if you look north, to the bole of the state, you see one of the darkest areas.

What is out there? Who is out there? My ignorance is encyclopedic.

With friends Didrik Johnck and Adam Rose-Levy we map out the long way through the backside of Nevada, from Las Vegas to Reno. We could fly this connection in minutes, or take the freeway in a day, but we’re going to take a week scrawling through one of the loneliest passages in the world.

We begin the journey from the Downtown Grand Hotel in Las Vegas, just footsteps from the action of Fremont Street, and a half-block from a celebration of the city’s notorious roots at The Mob Museum. We pack up, head out, freed from the arguments of civilization, and wind around Lake Mead to Boulder City.

Lake Mead looks as shimmering and desolate as it did when I was a river guide in my teens. I used to pilot inflatable rafts down the Colorado through the Grand Canyon, and the take-out then was Temple Bar Marina, about a day’s motor (we used 20 hp Mercs) across a brutally hot and barren channel. Sitting in the back of the 33’-long pontoon raft, the engine droning, the heat searing, I felt for the first time a seam open onto a void whose terrible content is the inevitability of finality, and it raced the blood and evoked feelings of being more alive. It was that kind of place.

We make our first stop at the Nevada State Railroad Museum in Boulder City, which harbors the train that carried the supplies to build the biggest dam in the world at the time: Hoover Dam.

Here I meet John, a retired engineer in full railroad costume, who offers to take me on a little ride in his engine. A conductor hanging off a Pullman coach yells “All aboard,” and off we chug.

The restored train doesn’t go far, about four miles, and John doesn’t say much, but I ask him “If a train station is where a train stops, what’s a work station?” He groans; puts the train in reverse.

From Boulder City we wheel across the Mojave Desert to the Valley of Fire, Nevada’s oldest and largest state park, but still just a fragment of the over two million acres of designated wilderness in Nevada. It erupts from the land like a big pot of calcified soapsuds. The 150 million-year-old rock is mostly blazing red Aztec sandstone, eroded into phantasmagoric lumps and wedges. Steve Santee, a ranger who lives in the park, hands me a passport, as though he’s recruiting me for some sort of escape. (I came for the waters…. I was misinformed). Turns out the passport is the centerpiece of a program designed to encourage visitation to Nevada’s 23 state parks, some of which are distinguished for their lack of callers.

Steve explains that once passport holders have their booklets stamped at 15 different parks, they earn one free annual pass to all Nevada State Parks. He stamps mine; I’m on my way.

The sun is quickly falling, so we head up a low ridge to Rainbow Vista, an overlook of washes, dendritic mazes, domes, towers, ridges and valleys, and bands of colors, sandwiched like the stratum where peanut butter and jelly meet. The view tumbles like layers of life, and it seems, if I look hard enough, I can see the whole of my personal span in these rocks.

Then, beneath the scarp of purple nightfall, we’re off up the Great Basin Highway, running through a watershed named by explorer John C. Frémont in the mid-1800s. The region comprises not one but at least 90 basins, or valleys, and its rivers all flow inland—not to any ocean. If you are running water, you can check in, but you can never leave. Livin’ it up in the Hotel Nevada.

Under a stanza of stars, seemingly amplified by the high desert air, we find our way to a set of cabins on a ridge under a windmill outside of a former horse thief resting station called Alamo.

Even with a bakery featuring generously-sized homemade pastries, it does seem like a last stand.

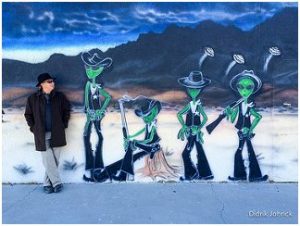

The day next, beneath a beckoning blue sky, we probe up the road, with a speed limit of Warp 7, to the intersection with State Route 375, which in 1996 was renamed the “Extraterrestrial Highway,” for the many UFO sightings along this naked stretch of road. The highway is adjacent to Area 51, the super-secret Air Force test facility, whose existence the U.S. Government didn’t even officially acknowledge until recently, and which many believe is holding a ménage of little green intergalactic pilots and their downed spacecraft.

There is a single shop at the intersection, ET Fresh Jerky, with a large sign out front “DROP YOUR TOXIC WASTE IN THE CLEANEST RESTROOMS IN AREA 51. FREE SAMPLES.” Who could resist? We park, and walk in. Aliens do have the power of mind control.

Inside I meet manager Dixie Scabro. She’s quite friendly, happily ringing up my purchases, but none too chatty. I ask if there might be any relationship between alien cattle mutilations and this jerky outlet. She shakes her head no. I probe some more, asking about Area 51, just beyond her doorstep, but she just clams up. What secrets is she hiding? She won’t tell. Instead, she directs me to the Alien Research Center, just down the road. “But, it’s never open,” she warns.

So, we head down the ET Highway to a giant metal statue of a goofy-eyed alien standing in front of a Quonset hut (I was born in a Quonset hut, adding to the mystery). It turns out it is indeed open, and so we venture inside to a galaxy of Martian t-shirts, X-Files posters, space gimcracks, UFO tchotchkes and an empty bottle of Alien Tequila. Someone, it seems, drank the research before we showed up.

Back on our telluric adventure we weave through a landscape that looks as though left in the sun too long. We stop at Caliente, named for the hot springs in a cave at the base of the surrounding mountains.

It was once the center of a railroad war, as it is the half-way point between Salt Lake and Los Angeles and rival barons wanted to own the tracks. When steam engines were replaced by diesel locomotives in the 1940’s, the division point moved to Las Vegas. Now Caliente seems the backside of an idea, more wish than reality, a semi-ghost town with about 1000 residents.

Here we meet Mayor Stana Hurlburt, whose office is in the old Spanish mission style railroad depot. She shares she is hoping to reinvigorate the town by turning it into a mountain biking mecca, similar to Moab.

It has the terrain, to be sure, and no crowds or spandex, yet. She may be on the right track.

We round out the day visiting Cathedral Gorge State Park, a long, narrow valley where erosion has carved stagy spires and basilicas in the soft bentonite clay. It looks like the maria of the moon.

Ranger Dawn Andone takes us on a hike through earth’s artistry, into twisting slot canyons, around church-like steeples, beneath buff-colored cliffs, and by the fluted hoodoos carved from remnants of a great freshwater lake millions of years old. “How did all this happen?” I ask. “Sedimentary, my dear Richard,” explains Dawn.

Under the dark clock of night we make our way another six miles up the road to Pioche, once the baddest town in the West, badder than Tombstone, Deadwood or Dodge City. In its heyday as a silver mining center it had 10,000 residents, 100 bars, and 100 whore houses. Now it’s another living ghost town, and we take the night at the only accommodations around, the old haunted Overland Hotel & Saloon.

We break the seal of night with a home-style breakfast at The Silver Café across the street. Then, we hook up with local historian and amateur gunfighter Jim Kelly who offers to show us the Boot Hill Cemetery, where, in its boom years, 72 people died of lead poisoning, croaked with their boots on, before anyone died of natural causes.

In 1873, the Nevada State Mineralogist reported to the State Legislature “About one-half of the community are thieves, scoundrels and murderers.”

Alongside Murder’s Row, a section in the cemetery with markers for over 100 murderers, Jim hands me a six-shooter, and challenges me to a gunfight. Somehow, I win, and he crumples like a kicked tent down onto the grave of his great grandfather, shot down by local rival.

Back at the long cherry wood bar, both staff and guests alike talk about their encounters with ghosts, including bartender/maid Stephanie Haluzac, who speaks about the many spirits she’s faced over the years. Once she was in the laundry room folding a towel when a heavy glass ashtray came flying across the room. She gave up smoking then and there.

Next we hare past fields of alfalfa and through a couple of state parks centered around man-made reservoirs, Echo Canyon and Spring Valley, both of which might be designated Ghost Parks this time of year. Almost like a Twilight Zone episode, or The Rapture, every human seems to have been plucked from the landscape, though all the facilities…bathrooms, picnic tables, campgrounds, boat launches, information signs, a stamp machine for the state park passports…are perfectly presented, waiting for a dinner party. It’s nice having these resplendent parks to ourselves, and we take some short hikes, skip some rocks, take some pictures, and then start driving north.

Looking at the map, it seems there might be a shortcut over the Mount Wilson Byway Road. It’s a gravel road, almost entirely through BLM land, that crooks through a volcanic caldera overgrown with pinyons, junipers, and, as we climb higher, snow. This is a stunning drive, past high peaks, around councils of aspens, ponderosa pines, and the exquisite non-existence of right-angled civilization. Even in our GMC Yukon, in four-wheel-drive, we skid and swerve in the ice and snow, sliding sometimes like a fried egg on Teflon, but finally crest the snow-covered pass at 8,900’, looking over to the great girth of original country, and beyond to a sere horizon.

Then we slowly unwind the back side, calipering back down to Route 93 as the encasing mountains slip by like a vast coffee cake with powdered sugar on top. Once back on the straight and narrow we roll northeast to the border, passing along the way herds of roan horses, wild and running, more here than in any place in America.

We drive into the thick, dark wings of night, and finally reach the Center of Nothing, Nevada, featuring the Border Inn Casino, which is half in Utah, and half in Nevada. My phone at bedside can’t figure out the time zone, as Nevada is an hour earlier than Utah, and the digital clock keeps beeping and bouncing between the two.

It’s a chilly, stelliferous night; I can reach up and nearly touch the spill of The Milky Way. It’s so bright I cast a shadow.

This is a privilege, and ancient right. More than two thirds of the U.S. population, about half the EU population, and one fifth of the whole world lives where the possibility of seeing the Milky Way with the naked eye is no longer. Here, it is practically splashing into my lap.

In the soft matutinal light of the new day we make the short drive to Baker (population: 68), then up towards Great Basin National Park, the only National Park in Nevada, and one of the park system’s least-crowded. Along the way we pass a long series of fence posts festooned with whimsical art, from carvings to car parts, tin cans to horseshoes, sculptures to paintings, scarecrows, mannequins and aliens…it’s what locals call “Post”-Impression Art.

At the visitors center we meet Ranger Kelly Carroll, who offers to show us around (we are the only visitors at the moment), and takes us on a short walk in the shadow of Mount Wheeler, second tallest peak in the state. The park is home to the oldest trees in the world, and Kelly tells the story of geology student Donald Currey who, in 1964, came to study ice age glaciers at Wheeler Peak, collecting tree ring data. In a Bristlecone pine he was sampling, his coring got stuck. So he asked permission from the U.S. Forest service to cut down the tree. Once cut, and the rings counted, there was this realization that the felled tree was almost 5,000 years old, the oldest tree ever recorded.

Since then, older trees have been discovered, but their locations are kept secret.

Another ranger, Robb Reinhart, then takes us on a tour of Lehman Caves, one the country’s most richly decorated caverns. Once inside this helical pit, Robb leads us through a limestone and karst passageway on a journey to the center of the earth, or at least toward the fantastic fallout of hypogene forces: speleothems, dripstones, shields, sensuous flowstones, esophagus-like tunnels, clear pools, and the carrot-shaped stalactites and stalagmites (memory rule: stalactites hang tightly from the ceiling; stalagmites might someday reach the ceiling) that grow a centimeter every thousand years.

It’s a fairytale world, artfully lit, and I vow to return to bring my sons, and to climb Wheeler Peak.

Now we head west on Highway 50, the former Pony Express route. An ad in 1859 read: “WANTED. YOUNG, SKINNY WIRY FELLOWS. Not over eighteen. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. WAGES $25 per week.”

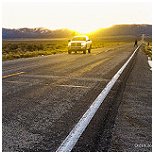

The route is now known as the Loneliest Road in America. In 1986, Life Magazine ran a negative article about Nevada State Highway 50 entitled “The Loneliest Road.” An AAA spokesperson had described the route through Nevada in these words: “It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it. We warn all motorists not to drive there unless they’re confident of their survival skills.”

So many things about Nevada seem counterintuitive, and in that vein, Nevada tourism officials seized on The Loneliest Road pejorative as a marketing slogan, and created signs, stickers and brochures touting such.

They were right, though, as the lonely quality also makes this one of the most sublime corridors I have ever experienced.

Much of the time it reminds me of Jerry Bruckheimer’s film intro logo, the boundless straight road and the lightning bolt. After hours of nothingness, it seems we’re driving ever closer to the origins of the earth. A tumbleweed sweeps across the road, whispering some hoary invitation to explore beyond the pavement.

So, we make a short detour down a gravel road into the Ward Charcoal Ovens State Park, featuring a series of six 30’-high beehives built in 1876 to burn locally-harvested timber for use in smelters at a nearby mine. As usual throughout the trip, we are the only ones here, and we step in and out of the giant charcoal kilns, self-stamp our passports, and vanish down the road.

We seem to be navigating a large unfurnished chamber in this next stretch, but it is an occasion with room to think; room to breathe. The interstice is rich here.

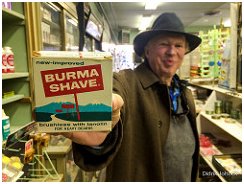

In the little community of McGill we stop at the Rexall Drugstore, but it’s not like my neighborhood Walgreens. Stepping inside is like stepping through a time-warp, as though half a century ago the owner went out for a cigarette and never came back. Daniel Braddock, dressed like my grandfather’s pharmacist in bowtie and white paper hat, greets with “Good afternoon. Welcome to the Past.”

The shelves are lined with faded products dating back to the 1950s, from the once popular Dippity-do styling gel to Ipana toothpaste. Daniel, an irenic soul who makes peace with the past, gives an archeological tour down the memory lanes, finally showing off the space in the back where home remedies and prescriptions were mixed in-store, next to stacks of original invoices, dating back to 1915.

Before we leave he dollops double scoops of ice cream at the old fashioned soda fountain, and hands them to us to lick vanilla memories.

After days of nights in darkness, we pull into the neon wash of Ely. The road has rendered me unfit for glitter, so I sit in the car decompressing for a few minutes before checking into the Hotel Nevada and Gambling Hall, which has its own little walk of fame out front. There are stars in the sidewalk for Pat Nixon and Lyndon Johnson, and when I ask the receptionist why the stars, he replies they are for celebrities who stayed at the hotel.

“Pat Nixon and Lyndon Johnson. Same room?” I can’t resist the query.

The receptionist draws a sly smile; silently hands me the key.

We take dinner across the street at the Cell Block Steak House, in which diners sit in jail cells, and are served behind bars by waiters with sheriff badges. The Gunslinger New York steak is to die for. If this is the grub in jails here, I confess to shooting Jim Kelly back in Pioche. Lock me up.

At checkout the morning next I’m handed a little book, “The Official HWY 50 Survival Guide,” which can be stamped at businesses and museums along The Loneliest Road, working towards a state-issued certificate of commemoration. With the day still crisp we head trundle to Eureka, another town defined in ways by what is not there. It was a busy smelting center in the late 19th century, and nicknamed “Pittsburgh of the West.” But, as with most towns along this route, the mines petered out, and ever since it has been the Big Wait for something to happen next. It today vaunts itself as “The loneliest town on the loneliest road.”

We venture into the Owl Club Bar and Restaurant, noteworthy for its imposing taxidermy, and its jukebox that features pretty much every song ever written. It’s also a hall of history; of gunfights, dances and rollerball (it was once “The Rinky Dink Roller Rink”). We share lunch with recent owners Eleny Mentaberry and her bar-tending husband Scooter (he calls himself a Precision Carbonation Specialist).

Scooter is part Basque, and there are quite a few in the area, immigrant sheep herders who found the landscape welcoming. He orders me a picon punch, a concoction that includes grenadine, club soda, a float of brandy, and Amer Picon, a bittersweet aperitif made in France with herbs and burnt orange peel.

It’s apparently a Basque-American concoction, without antecedent in the old country, and is now the unofficial state drink. I knock it back. It’s tart, a little aggressive. With the glass empty, I’m reeling… “Like a woman’s breast, one is not enough; three, too many,” says Scooter, as he pushes another in front of me. I pass. I am supposed to drive this next section, but I buckle into the back seat with new admiration for the Basques.

We glide along like a boat, as if the road is a river, and veer down State Route 376, then down an unpaved spur to the hamlet of Kingston. We park at Zach’s Lucky Spur, a shack of a saloon in the shadow of a rickety windmill, the only watering hole in a town of about 70 folks (and quite a few dogs…one is sitting at the bar sipping a beer as we venture in.) Men’s Health magazine cited it as the “Best Bar in the Middle of Nowhere.” In Nevada, it seems, there is an inverse relationship between the emptiness of the landscape and the quantity of objects inside shops, hotels and bars.

Mike Zacharias, the owner, says “It’s easier to say what I don’t collect.” The place is packed with a ludic array of cowboy photos and art, including over 100 spurs. Somewhere along the way he picked up Rory Calhoun’s vest, which he is sporting as he sips and spins tales. There’s a fantastic story behind every ornament and picture, and it’s easy to be certain of them all. At one point Zach says “I used to ship bulls for a living…shipped them all over the globe. At one time I was the biggest bull-shipper in the world.” I do believe the man.

We’re at about 6,000’ elevation, and after a couple of Icky IPAs (named after Nevada’s official state fossil, the Ichthyosaur) I wobble a few yards down the hill to Miles End B&B (owned by John and Ann Miles, and their dog Zee), a fetching wilderness retreat with a stone lodge (called “Valhalla”), a patch of grass (first green I’ve touched in days), and a wood-burning barrel hot tub, where I soak for a spell under a sky plush with a million points of light. Putting my head back against the oak rim, I feel like I’m falling upwards.

In the new day, after John’s blueberry pancakes, with sides of local fresh ranch eggs and toast with local honey, we head out again, tooling north, past a billboard that proclaims, “What Happens in Austin….You Brag About.” We are approaching the geographical center of the state. At its peak 10,000 people based in Austin, and the roaring silver camp produced some $50,000,000 in ore. But, with the mines spent, people left as enthusiastically as they came. Now, the population sits at around 300 folks.

After a stop at the Toiyabe Café (killer hand-made milkshakes), and a gem-buying spree at the Little Bluebird Turquoise Shop (where I also buy what appears to be the authentic Aladdin’s magic lamp, and get my Loneliest Road passport stamped), we coil up a hill southwest of town to Austin’s most famous attraction, Stokes Castle.

It’s not really a castle, but a crumbling three-story granite tower built in the late 19th century as a summer residence for a mining baron. Modeled after a family painting of a villa outside Rome, it is now a ghost of a remnant of a vestige of a trace of an era lost to time. In the early 1950’s a promoter tried to buy it with intent of moving it to the Las Vegas strip. But, a cousin to the original owner grabbed it instead, preserving its place, but letting it dissolve into disrepair. Only the view remains intact, overlooking the meandering Reese River Valley. From here, it feels like we could fly.

Under a lowering sky we stop by something in the middle of nothing, a stately cottonwood blooming with polymer beauty. It’s a shoe tree, draped with hundreds of pairs of Nikes, adidas, pumps, boots, ballet slippers, even stilettos from nearby brothels, all spinning in the breeze like clinquant finery.

Rumor is the first pair was thrown during a wedding night argument by a young couple in the 1980s; later, their children’s shoes were added to the bough; then other relatives, and friends, and passersby, and a tradition was borne. It became, in short order, the world’s largest shoe tree. But what we are witnessing is not the original, which was chain sawed down by vandals on New Year’s Eve, 2010. Hundreds cried with the news. Now, a sister sapling, a few yards away, has become the replacement shrine, and something of a cause, and it seems to have sucked up all the discarded footwear in Nevada.

Just a hop and a shoe’s toss away we pull into Old Middlegate Station, the actual “Middle of Nowhere,” population 17, home of the Monster Burger. Fredda Stevenson, owner with husband Russ, tells how she created the triple-decker pounder, which has assumed the status of legend, and draws burger slayers from around the world. She recalls that when a regular client complained her patties were too small, she decided to go all out and create something that would more that sate the hungry man.

“What happened to the customer?” I ask.

“Died of a heart attack,” she says.

She has rules for consuming the Monster Burger, which earns a t-shirt (“I Ate the Monster”) if a challenger can finish it within her assizes (you can’t leave the table once you sit down, and you have to eat the mound of fries and fixings). I accept the dare, and, she sets down a jacked stack of beef as big as my head…it’s the LaRon Landry of burgers. After an hour, I’m shaking in defeat. Fredda struts over to my table and plants a white flag in my remaining meat. “Richard, you’re not the first guy I made a wus out of. The monster got ya!”

This next stretch of highway delights the eye, and the soul. Graceful sand dunes undulate with waves of pale, beige sand; high mountains rise, frozen like giant whitewater waves. I can hear my blood pulsing in awe.

Out final stop is the Frey Ranch, 8 ½ miles south of Fallon, ground zero for Nevada’s craft liquor movement. In the last tail feathers of the day, we roll down a painterly lane, past barns, silos, vineyards, a line of old John Deere tractors, a gazebo, and a Prairie-style homestead built in 1944. Here we meet Colby Frey, who is making high-end, high-tech spirits at Nevada’s first legal commercial distillery.

Colby is a fifth generation farm boy… his ancestors owned some of the first deeded property in Nevada.

Now, he’s using the 1200-acre family plot for 21st century liquid innovation. He’s crafting vodka, gin, brandy, grappa, bourbon, absinthe and single malt whiskeys, all from grains and ingredients grown on the farm; all mashed, fermented, distilled, filtered, barreled and bottled just feet from where they were harvested. Even Whole Foods can’t claim such an integrated, micro-localized, grain-to-glass operation.

In the understated, wood-trimmed tasting room, we sample some of the signature spirits. Colby pours a glass of gin, made, he says, from sagebrush, coriander, Angelia root, cardamom pod, lemon peel, orange peel, and, of course, juniper berries. He asks me to whiff the bouquet before a sip. “Smells like a rainy day in Nevada,” he says. I can’t vouch for that, but am impressed enough with its creamy texture and taste to depart with a bottle of Frey Ranch gin in my bag, ready to take home and mix with tonic as my regular anti-malarial.

Towed by the sunset, we arrive in Reno. It’s raining. Smells like gin. An earned week after we began this road trip we check into the Whitney Peak Hotel, right on Virginia Street, right next to the famous Reno Arch sign, and a living temple to the evolution of consciousness in Nevada.

This was once Fitzgeralds Casino-Hotel, and the location is prime, but it is now a luxury boutique non-smoking, non-gambling full service hotel, themed around a giant climbing wall, tallest in the world. In a way it is an urban tribute to the mountains, lakes, and wild steppes we just traversed, trying to bring Nevada’s epic Outside in.

You have to get over the color green to appreciate back-country Nevada; you have to give up on the commonplace, conventional jobs, standardized architecture, fences and routine. Even the idea of average doesn’t fly here. This is the geography of hope, a puzzle of empty spaces and outsized personalities, of waterless riverbeds and spates of rich-soil stories. For someone like me, the pull is inexplicable, but irresistible, and in the end, the only thing to do is capitulate… to embrace the characters steeped in defiant vitality and wit; to the carousel of spirits in this stark matrix of mountains and basins; and to the singularity that with a journey like this beautifully draws the soul into itself.

On this trip through the backlands of Nevada I may not have gone where I intended to go, but I think I ended up where I was intended to be.

Leave a Reply