John M. Edwards, a paparazzo of the paranormal, stalks the The New Yorker’s most famous and fiendish poltergeist cartoonist back to his moody hometown: Westfield, New Jersey.

John M. Edwards, a paparazzo of the paranormal, stalks the The New Yorker’s most famous and fiendish poltergeist cartoonist back to his moody hometown: Westfield, New Jersey.

“Give me a place to stand on, and I will have the earth.”

–ARCHIMEDES

In Westfield, New Jersey, I finally found the moody manse of cartoonist Charles Addams, probably The New Yorker’s most famous and fiendish cartoonist, and also the inspiration for the TV series “The Addams Family,” as well as a series of freaky film spinoffs.

Come on, it doesn’t get any better than this—snap! snap!

“Lurch” on a harpsichord, grumbling. . . .

“Uncle Fester” illuminating a lightbulb in his mouth. . . .

“Cousin It” just because. . . .

Charles Samuel “Chas” Addams (7 January 1912–29 September 1988) is known as a master of macabre black comedy, the cartoonish version of

Roald Dahl or John Collier. Distantly related to presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, Charles Addams was always wallowing in wealth and privilege. Despite his demotic associations with New York, Addams was born right in the nearby Colonial Main Street Garden State USA suburb of Westfield, New Jersey, where he was known as “something of a rascal around the neighborhood” by some old-timers who knew him well, including an aging barbershop quartet with their very own 19th-century antique striped pole.

Known as a “ladykiller,” Addams, once success struck like lightning from his very first drawing of a window washer for The New Yorker on 6 February 1932, decided to live the good life on his own terms. “Chas” was often seen on the arms of glamorous grand dames at social events (including parties, soirées, balls, and fundraisers), with such purty celebrities as Greta Garbo, Joan Fontaine, and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Of course, rumors were rampant.

Even so, “Chas” managed to get married three times, all to women who vaguely resembled “Morticia Addams.”

Although Addams created the “Addams Family” in 1938, his work was stymied somewhat with the arrival of World War II, when he worked for the Signal Corps Photographic Center making animated training films for the U.S. Army.” But when Addams met his first wife in 1942, he went back to the drawing board, bowled over by her enthusiasm. This first marriage ended over a dispute about whether or not to have children. Needless to say, Addams was against. There is no good reason now to give out her name.

Addams’s second wife was a practicing lawyer named Barbara Barb, whom he married in 1954 and divorced in 1956, because she was bossy and insisted on signing him up for a risky life insurance policy. The last straw: supposedly Barb insisted that “Chas” register as an “organ donor” in case of an accident, like a character out of HBO’s “Dexter.”

Yikes.

But at last, Addams met the right woman, named “Tee” (Marilyn Mathews Miller). They married in a creepy pet cemetery and moved in 1985 to a property called “The Swamp” in Sagaponack, New York. Here they lived in an eerie fantasyland straight out of a Tim Burton production.

Yet Addams still dreamed about someday returning to his home town in the Garden State.

Even though I was born in California, I grew up in nearby Plainfield, New Jersey, a short drive to Westfield down South Avenue, which vaguely stretches alongside the Raritan Valley Line to Penn Station Newark, New Jersey, with a change to Penn Station New York, New York, which for obvious reasons is confusing for recent swarthy new immigrants.

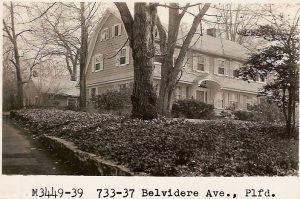

Past the turnoff for Westfield on Route 22, the second most dangerous highway in United States after the L.A. Freeway, I turned off at the Watchung Exit and drove through the drug-dealing blight of downtown Plainfield, until I arrived at my old house at 735 Belvidere Avenue, on the corner of Belvidere and Berkeley, a fantastical greenish gray Dutch Colonial which by paradox seems bigger inside than outside.

It is still there, even though two mansions across the streets burned down in suspicious fires long ago.

One of the mansions was owned by “Old Man Hatchet,” an eccentric millionaire member of the Talmadge family, who had been scaring neighborhood kids for decades. On my block alone were other kids in each house to play pretend, spying on the old coot who purportedly kept kidnap victims in a dungeon in the basement, such as usually happens in slasher horror flicks.

An enthusiast of memorabilia, including Forry Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland magazines, I played with Robbie Connell, Sandy Maddox, Scott Levy, Tommy and Patty Worth, but not with any of the Louiseaux boys (including a retart named “Jocko”), who were dangerous to hang out with, often ending up in painful apple-throwing wars or a dangerous game of RedEye ™, the hard plastic ball with spikes which my parents forbade since it could “take an eye out.”

I still remember the TV ad from the eighties: “RedEye, RedEye, that’s the name, catch the red spike and win the game!”

Anyway, the Talmadge Mansion was clearly what influenced nearby neighbor Charles Addams’s Mansion. It was the spitting image of it. His own digs in Westfield seemed too bright and Victorian to be harboring a dangerous genius. (Westfield also has the home of the real-life serial killer from the film “The Stepfather.”)

So one day as a young kid I looked out the window and saw Old Man Hatchet’s Mansion go up in flames, but with no sign of the Louiseauxs around. Mr. Cooper, whose witchcrafty Tudor house abutted Old Man Hatchet’s land, speculated that it might have been burned down by the mafia for insurance money.

I secretly suspected poor old gullible Robbie Connell, nicknamed “Tushy” by the mean neighborhood kids, to be the main suspect, now that he irreverently smoked stolen cigarettes from his older half-brother Richie like a teenager, and was blamed for everything anyway.

(One day as a prank I convinced Robbie to lick a streetlamp pole and his tongue got stuck, and we had to call the frigging fire department.) To avoid slander, I suspect these days that Robbie ended up a successful businessman, so I will not speculate on his possible apocryphal involvement in the firestorm.

Ever see that scary old episode of “One Step Beyond,” when a little girl can start fires with her psychic powers, which eventually influenced Steven King’s “Firestarter”? Well, you get the picture then.

Grandpa Bob soon came to deliver an entire collection of hardcover Charles Addams cartoon books, perhaps as a consolation prize, thus confirming that he knew something about the Talmadge residents that we had not quite grasped. Yep, that’s it, I thought, paging through the fiends from across the street: Gomez, Morticia, Wednesday, Pugsly, Lurch, Fester, It.

Years later I moved to Westfield, New Jersey, above the now-no-more Tullio’s Hair Salon and down the street from the now-so-missing Excellent Diner (bought and removed by Pied Piper Germans from Bremen), but it wasn’t until recently that I made the pilgrimage to Charles Addams’s house, which I must reiterate was too sunny to be the abode of monsters fair or foul. But the old colonial town, reportedly once a Tory enclave, has some supernatural shifts to it, such as the old Revolutionary War graveyard, across the street from the clapboard Protestant church, with headstones dating back to at least 1720, sculpted with angel or vampire wings, looking like Mad Mozarts.

Hence, I decided to pay a visit to a house on Elm Street, a real-life “Nightmare on Elm Street,” but with Charles Addams instead of Freddy Krueger.

Unfortunately, it looked just like any old house.

A graduate of Colgate, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Grand Central School of Art, Addams drew “with a happy vengeance” according to some of his close friends, whom included Ray Bradbury. He drew cartoons first for the Westfield High School literary magazine Weathervane. And then he went on to True Crime, where he supposedly and cryptically “wiped the blood off of layout photos.” But he didn’t get famous until he started getting into the big magazines, with over 1,300 drawings featured in The New Yorker, Collier’s, TV Guide, and Mademoiselle.

On 29 September 1988, Adams died of a heart attack in the ER at St. Clare’s Hospital and Health Center in New York City. His ashes were buried in his last home “The Swamp,” although many believe rumors that his urn was dug up by complete strangers and returned to his ancestral terroir in Westfield, New Jersey.

Pals with Hitchcock, Addams was referenced in the film “North By Northwest,” when the character played by Cary Grant quips, “Now that’s a picture only Addams could draw. . . .”

Addams’s eldritch artwork went on to influence some of today’s weirdest and wackiest cartoons, such as “The Far Side” and “The Simpsons.” Not to mention his main friendly competitor in strange occultist sketches: Gahan Wilson. On his deathbed, it is rumored,Addams said he preferred to be known as a “great cartoonist” rather than an “okay guy.”

We have to agree, since, unlike Rod Serling dangling his trademark cigarette, we do not really have any idea what Addams looked like.

Except for this picture captured (no: stolen) from the Internet.

FURTHER READING BY ADDAMS

Dear Dead Days, with The Addams Family on the cover.

Books of Addams’s drawings or illustrated by him:

• Drawn and Quartered (1942), first anthology of drawings (Random

House)

• Addams and Evil (1947), second anthology of drawings, (Simon and

Schuster)

• (illustrations) Afternoon in the Attic (1950), John Kobler’s

anthology of short stories

• Monster Rally (1950) third anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

• Homebodies (book) (1954) fourth anthology of drawings (Simon &

Schuster)

• Nightcrawlers (1957), fifth anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

• Dear Dead Days: A Family Album (1959), compilations book of photos

(G.P. Putnam & Sons)

• Black Maria (1960), sixth anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

• Drawn and Quartered (1962) re-released (Simon & Schuster)

• The Groaning Board (1964), seventh anthology of drawings (Simon &

Schuster)

• The Chas Addams Mother Goose (1967) Windmill Books

• My Crowd (1970), eighth anthology of drawings (Simon & Schuster)

• Favorite Haunts (1976), ninth anthology of drawings (Simon &

Schuster)

• Creature Comforts (1981), tenth anthology of drawings (Simon &

Schuster)

• The World of Charles Addams, by Charles Addams (1991), posthumously

compiled from works with the copyright owned by his third wife, Marilyn

Matthews “Tee” Addams (Knopf)

• Chas Addams Half-Baked Cookbook: Culinary Cartoons for the

Humorously Famished, by Charles Addams (2005), anthology of drawings

(Simon & Schuster)

• Happily Ever After: A Collection of Cartoons to Chill the Heart of

Your Loved One, by Charles Addams (2006), anthology of drawings (Simon

& Schuster)

• The Addams Family: An Evilution (2010), about the evolution of The

Addams Family characters (arranged by H. Kevin Miserocchi)

ABOUT ADDAMS

• Davis, Linda H., Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life (2006), Random

House, 382 pages

Leave a Reply