The taproot of the tree of civilization, Iran. While the USA is an entity less than a quarter a millennium young, Iran’s recorded history bows back 5000 years. At its height, about 500 B.C., Persia controlled more than 2.9 million square miles of land spanning three continents, east into India, south to Egypt, westward to Greece. It reigned over roughly 44% of the world’s population, making it the largest world power ever by population percentage.

Yet, the ebb and flow of time saw the region conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, by Arabs during the great expansion of Islam in the 8th century CE, and by the Mongol Empire in the 13th. Every time, it has risen again to create another borderland with a deep and unceasing identity. When it comes to putting today’s international squabbles into perspective, Iran takes the long view.

I first visited Iran in 1978, stepping off a Pan Am 1 flight to a city that seemed little different than ones in the West. Women wore mini-skirts and jeans, discos blared, and every hotel had a lobby bar. But, the gap between haves and have-nots was Grand Canyonesque, and there was at once a popular snap that ousted the Shah, and ushered in the Islamic Revolution.

It is with some unease but much excitement that I step to the Immigration desk at Tehran’s Imam Khomeini International Airport. I tense a bit when the officer takes my passport and pulls me aside. I’m left alone at a separate desk while my passport and visa are inspected, and cross-checked in a computer, but with a beam it is returned and I am waived through. Nobody checks my luggage, which is purposely innocent. I now wish I had brought the new John le Carré book.

It is nighttime, and the hour drive from the airport passes Khomeini’s tomb, a sprawling gold domed architectural piece that cannot be called humble. Covering some 50 acres, it is one of the largest monuments in the Muslim world, and one of the holiest, and therefore a target. In June of this year ISIS attacked the Mausoleum, killing one official and wounding a guard. Later we pass the iconic Azadi Tower, its four giant latticed feet thrusting towards the stars, a monument to the late Shah’s vaulting ambition. Its image is well known to American audiences of a certain age who were glued to the screen during the hostage crisis of 1979-80.

Along with seven colleagues, I am with a cultural tour organized by MTSobek, which has been operating trips to The Islamic Republic of Iran for several years (and operates the New York Times Journeys to Iran). We begin in Tehran, the kilometer-high capital, and to get an overview of its chaotic, mosaic-like layout, we take a series of lifts into the Alborz Mountains, to the Tochal ski mecca at 11,500’. It’s a bit disorienting to watch parties of women in hijabs, some draped in black manteaux, riding the téléfériques, but hiking, skiing and snowboarding are big sports here for the many. The other distinction is the number of bandages on noses, both men and women. Nose jobs are in vogue in Iran, and it is a badge of honor to wear the post-op bandage to telegraph the transformation. Surgeons of all stripes are distinguished in Iran. Hadi, our guide, says that one tour group gave him a heart attack, but he was saved by a local heart specialist. I can relate. I had a similar saving grace at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles. It was a brilliant Iranian cardiologist who pioneered a procedure that corrected an atrial fibrillation I dealt with a couple years back.

While in line a grinning young man reaches out to shake hands, and congratulates us for being tourists in Iran. Several others join in for an orgy of handshaking and earnest welcomes. Then a woman in a chador asks, “Why do you think we are terrorists?” Today, we have no good answer.

At the summit we wander about and gawk at the high dry landscape, which could be somewhere above tree line in the Rockies or the Alps, and gaze down at the labyrinthine riddle of 14 million people below. It is windy and a bit nippy, so after 30 minutes we cable back down to the temperate city to tour its museums, mosques, carpet shops, a couple of the Pahlavi palaces, and the buzzing Central Bazaar. We pass the “Nest of Spies,” the former American Embassy where the hostages were held for 444 days. Today it is a museum showcasing left-behind spying equipment, alongside pieced-together shredded documents marked “Secret.” Diplomatic relations were severed during the Revolution of 1979, but wherever we go in today’s republic Iranians seek us out, shake our hands, welcome us to their land, and ask to take pictures with us.

For lunch Hadi suggests a popular local eatery, Moslem, but it is across the street from where the bus lets us off. This is a problem, as the most dangerous part of a visit to Iran is crossing the street, mad with cars, buses, trucks and motorbikes (all Iranian made). Hadi tells the story of an American who couldn’t cross one swollen river of traffic, and after two hours he calls to an Iranian on the other side: “How did you get there?” The Iranian calls back, “I was born here.”

Hadi shows us the way. He steps into the motoring craziness and holds up his hand like a traffic cop, and then waves for us to run across. The line for the restaurant goes around the block, beneath strings of patio misters that keep the wait tolerable. Inside the door the line continues, coiling up narrow stairs to a packed room with long tables. We order up tah-chin (saffron and yogurt rice, served with chicken and barberries), chelo kebabs, flat bread and Istor beer, alcohol-free as all public brews, and we dine as a musician plays a gourd-bagpipe called a neyanban.

Then it’s back again to cross the street, and to the Laleh Hotel, named for a tulip, a national symbol, and adjacent to Tehran’s version of Central Park. The ride to downtown illustrates the alternative universe that is today’s Iran…. every type of modern shop and restaurant lines the milling streets…this could be any Western city, except for one notable difference. There are no recognizable brands….no food or clothing or retail franchises, no Starbucks, Gold’s Gyms, UPS stores, Super Cuts, Kumon or any products we know (there are a lot of pirated iPhones, however.) Western credit cards aren’t accepted. The signed Iran nuclear deal in 2015 called for the removal of economic sanctions against Iranian banks, but so far the U.S. has not lifted them. And that means it is difficult to buy Western products, so Iran, with the world’s fourth largest oil and the largest natural gas reserves, has turned inward to create a parallel world of goods and services. Want to buy a Romex watch?

As the morning light spills down the slopes of the Alborz Mountains we make the drive along the jagged edge of Dasht-e Kavir, a great salt desert distinguished by its distant hills of biblical proportions. About six hours later we pull into to the brick and pisé outpost of Yazd. With a history that dials back 7,000 years, Yazd qualifies as one of the oldest living towns on earth. It is here the Zoroastrian religion found its first followers, promoting a dualistic concept of heaven and hell, and in time influencing the tenets of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It also advocates that hospitality is fundamental to a spiritual life.

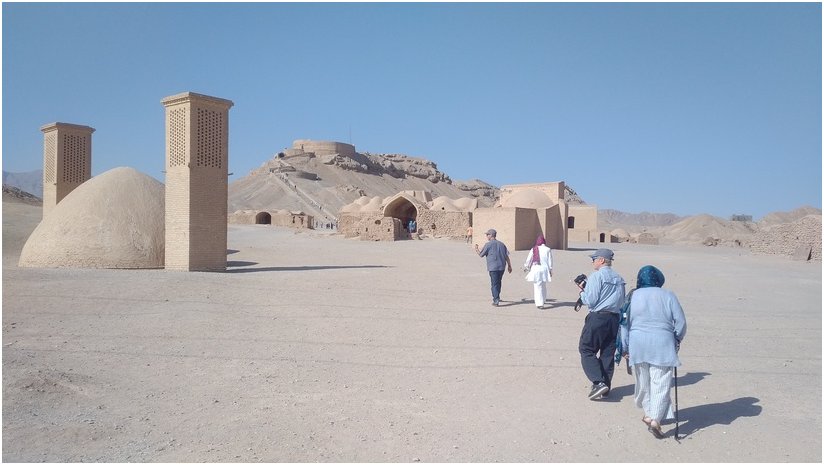

Just outside of town we hike to the top of a Tower of Silence, a circular raised structure where the dead were taken to be picked apart by birds of prey, similar to the Tibetan Sky burials. According to Zoroastrian beliefs, a body becomes impure at death, when evil spirits, or nasu, arrive to attack the flesh and soul of the deceased. By contaminating the corpse, nasu also threaten the living. Sky burial is considered a clean death because it prevents putrefaction—vultures can eat a body down to the bones in just a few hours. Hadi said the towers were still used until about 40 years ago, and he knows a woman who was walking nearby when a bird dropped a human finger on her.

Afterwards, we make a late afternoon trek to Saryazd to what is claimed to be the first bank deposit vaults, a series of small rooms in a protected adobe citadel where folks stored their precious personal belongings. This was once part of the Parthian Empire, whose army mastered a technique in which retreating horse archers would turn their bodies back in full gallop to shoot at the pursuing enemy. This was the origin of the term, “parting shot.”

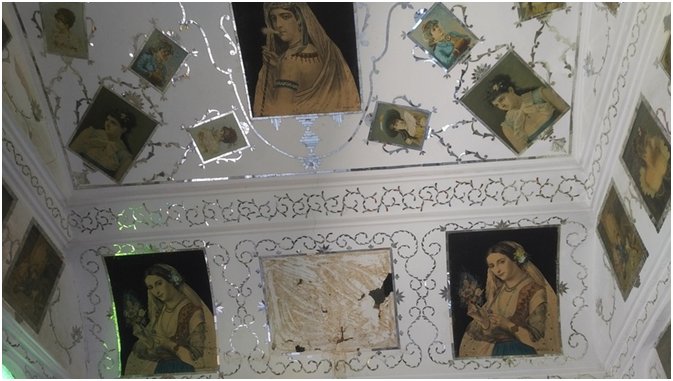

In the mid-morning heat of the following day we stand in mud-brick rooms beneath the cooling breezes of wind towers, badgirs, ingenious ancient systems of natural air conditioning designed to catch the sky currents and direct them downwards to the lower floors. We visit the Lari house (Khan-e Lari in Farsi), the mansion of a wealthy merchant family, built in 1860. Through its elegant archways, past the garden, we enter the artful bedroom of the teenaged son, who plastered his ceiling with portraits of beautiful young Western women, not unlike many male dorm rooms in mid-century America wherein Playboy centerfolds once adorned the walls and ceilings. Some notions are universal.

To wind out the day we make the long gritty trundle to Pire Sabze Chak Chak, the holy pilgrimage site for Zoroastrians. It is a long climb up a barren cliff face, a thousand steps to the grotto that serves as the shrine, and inside are three flames, meant to be eternal, like the Zoroastrian Fire Temple in Yazd, where a flame has been burning since 470 A.D. Fire represents the goodness and purity toward which all should strive.

There are several priests, keepers of the flames, drifting about, and I stand back and admire the hallowed scene. Then a woman steps in with her young son, maybe nine or ten years old. When she isn’t looking the boy leans into the flames, and blows them all out.

The priests rush to re-light, and our guide, Hadi, a man who seems to keep the heat of the desert at bay with his natural coolness, explodes in anger and scolds the mother. A few minutes later, everything is back to eternity.

Shiraz

Another day, another devastatingly beautiful drive, and we pull into Shiraz, the most liberal of Iranian cities, and once the wine capital of the region. Many of the women rakishly wear their scarfs towards the back of their heads, and the young use a filter app to access the forbidden Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

There are black banners strung throughout, and stalls selling self-flagellation chains, as we arrive during the annual Ashura celebration. It is a time of remembrance, as Prophet Muhammad’ s grandson, Husain Ali, was brutally massacred along with his family and followers in Karbalâ, now across the border in Iraq. The Day of Ashura is highly mourned by Shia Muslims, with a Passion Play re-enactment, and flagellation by male Shi’is. Whips, often with sharp ends, or even small knives are used to make backs bleed to commemorate the pain of martyrdom. We witness the scenes on the street, but our driver hastens past.

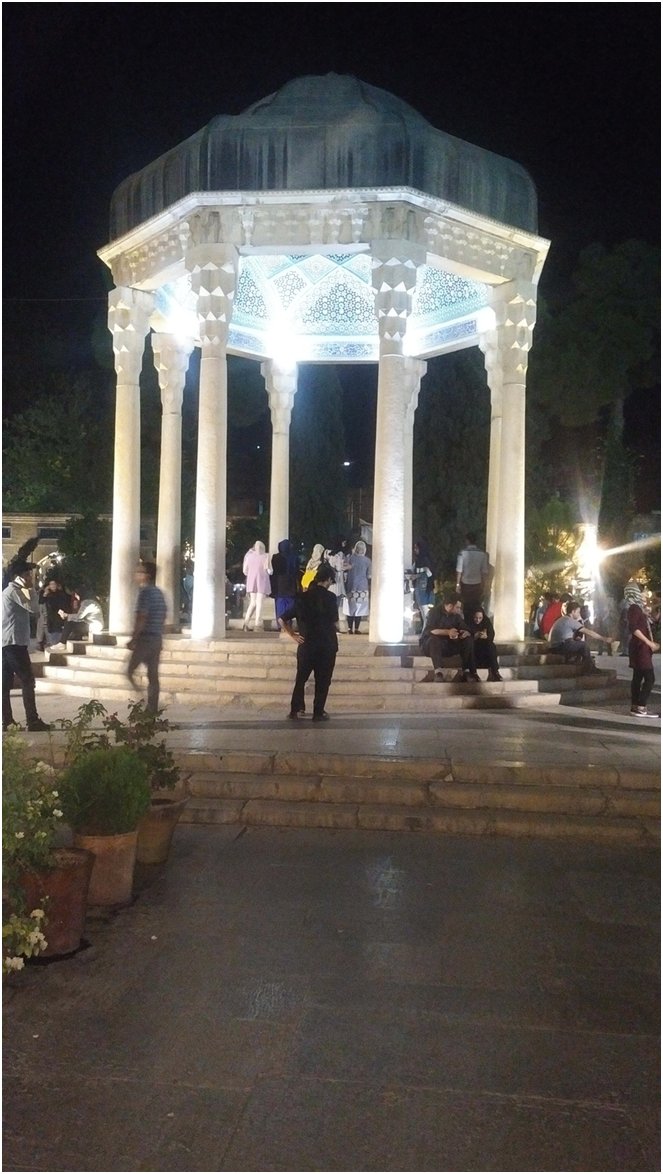

Here we visit a glazed tiled pavilion surrounded by fragrant rose gardens, water channels and orange trees: the marble tomb of Hafez, the 14th century mystic and Persian poet whose works are supposedly in every Iranian home. I have The Gift at my bedside, and when in college his verse was fireside fuel for romance, along with Rumi, Omar Khayyam and Ferdowsi, author of the Shahnameh, the longest work of epic poetry ever written, some 60,000 verses.

The story goes at the age of 21 Hafez, who was short and ugly, worked in a bakery and delivered bread to a wealthy ravishing beauty. He fell hard in love, and penned timeless verse to her. But she married a prince, so his love remained unrequited. But his poetry lives on, and the scores of couples here intoxicate (in the non-alcoholic sense) and fall in love with his verse.

At the hotel that evening an Imam approaches and asks where I am from. He is delighted I am an American. We banter for a bit, and he shares he has three wives. “How does that work in the household, in the bed?” I ask. He shakes his head. “They each have a separate house. It would never work under the same roof,” he explains, and then asks if I would like to come to his home for tea. “Which home?” I ask.

“Why, the home of my youngest wife, of course.”

With regrets I decline, as we are off to Persepolis.

Persepolis

The lavish ceremonial center of the Achaemenid Empire, Persepolis is just 60 kilometers from Shiraz, rising from a dry plain that looks like parchment. It is perhaps the most stunning ruin I have seen, surpassing even Leptis Magna in Libya. But, it is scarred by graffiti…I look aghast at the defiling scrawls, until my eyes pop at a signature: “Stanley, New York Herald, 1870.” This was Henry Morton Stanley, the African explorer who found David Livingstone the following year. Now I am truly impressed.

For 200 years the Kings of Persia ruled from here, and buried their royalty in elaborate tombs. It was a city of tolerance, testified by the well-preserved bas-reliefs showing guests from the many nations of the empire arriving at the palace bearing gifts. But, as always, those who own the newspapers, own the story.

Persepolis was burned to the ground by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE in an act of drunken destruction, but the columns, gates, monuments and ghosts that remain are humbling.

We also stop at Pasargadae to pay tribute to the tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the largest the world had ever seen, the first super power. He is celebrated as an advocate of human rights and respect for the customs and religions of those he conquered. He rescued the Jews when detained in Babylon, and guaranteed safe passage back to Palestine, and for that he is still lauded in the place perhaps most adversarial to modern Iran: Israel. Today about 30,000 Jews call Iran home, the biggest grouping in the Middle East outside of the Holy Land.

For many years I was on the board of International Rivers Network, a Berkeley-based non-profit that fights big dams. One was the proposed Sivand Dam, which some believe could flood Pasargadae, and the humidity from the reservoir would speed up the decomposition of Cyrus’s tomb. The dam was finished in 2007, flooding some 130 archaeological sites, and I can now see the valley where the waters have been stilled. But to date the lake has not been filled far enough to reach Pasargadae.

As the sun sharpens the sky we begin the long drive through the Zagros Mountains, passing the occasional nomad family traveling with sheep and goats to fresh pastures. We arc over a pass and down to the gardens of Isfahan, a city known in the 17th century as “Half the World,” as to visit was to experience that much of what the planet offered. It is insanely opulent and beautiful, even with its signature Zayandeh River bone dry.

We begin with a tour of a 17th-century Armenian Church, Vank Cathedral, which features all the overpowering architecture of grand European cathedrals. But it is a small museum showcasing the 1915 Armenian genocide, with photos, film and personal effects, that is most affecting. It is an enlightened policy to showcase this, a shameful episode in the region, but to acknowledge in such a powerful way is to attempt to persuade that it not happen again.

A walk away is the famous Royal Square (Naqsh-e Jahan), the second largest public square in the world, over five football fields long, and once the main polo ground and ancient equivalent of the Mustang Ranch for the Safavid kings. Hadi says they once used the heads of enemies as polo balls. And the 200 second-story apartments were pleasure retreats for indulgence in opium, wine and concubines.

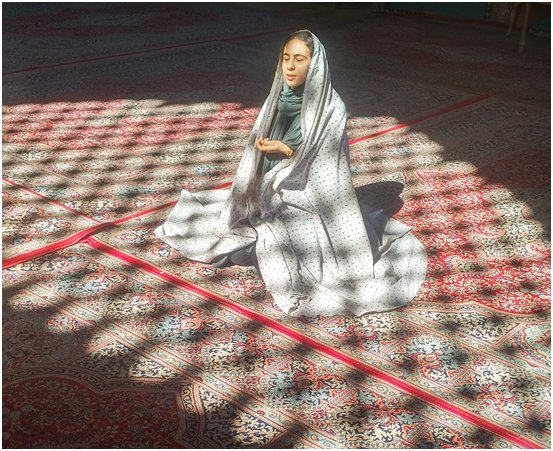

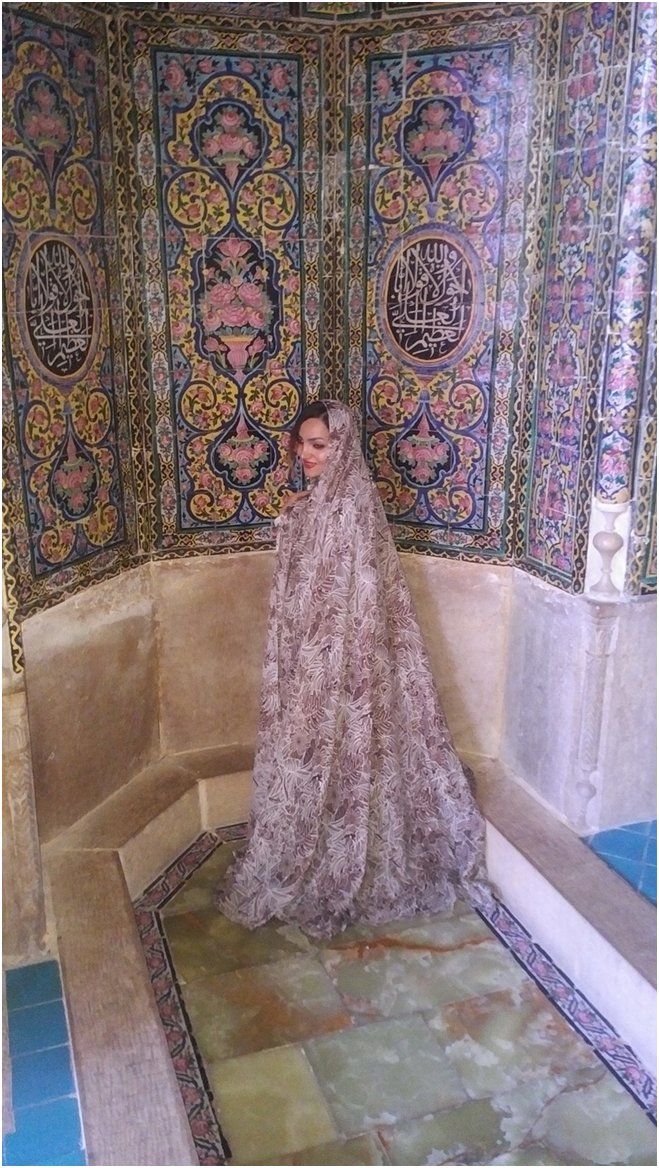

It is today a pleasant fountain-filled park with couples strolling and children skylarking. Along the middle rim is the Sheikh Lotfollah, the first ladies’ mosque in the Islamic world, accessed by women of the court via an underground tunnel. And at the far end of the square is the magnificent Blue Mosque, covered in an ocean of blue tile work. But what distinguishes the grounds today is that we are visiting during Sacred Defense Week, an annual commemoration of the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, during which there were as many as one million Iranian casualties. Lined up in front of the mosque are aging tanks, anti-aircraft guns, rocket launchers and artillery used in the eight-year conflict.

It’s an ominous sight, but perhaps more disconcerting is a huge banner strung across the end of the square that says in English and Farsi: “Down with America. Down with Saudi Arabia. Down with Israel.” It feels so reminiscent of the hostage period when every day on television we saw students and banners yelling “Down with the Great Satan.” But the sentiment belies all the welcoming and warmth we have experienced throughout Iran. Without exception, everyone we have met has been curious about us as Americans, and thoroughly welcoming, extending hands, planting kisses, inviting us for tea in their homes, smiling and sometimes offering gifts.

As we near the end of our journey we pass Natanz, the once secret uranium enrichment site which inspectors now confirm is hibernating, as per agreement. At our final stop in the oasis of Kashan we walk down a garden path near a group of women on a picnic. They all smile and wave, and then one comes running over and offers us slices of moist cake.

Legend has that it was from Kashan the Three Wise Men, the Magi, set out bearing gifts for the newborn Christ. The native generosity seems not to have waned. For a people with a long, fiery tapestry of rebellion and revolution, invasion and occupation, assassination and unrest, the one constant has been the proud Persian art of hospitality.

Later, I am walking down an alley, and an Iranian-made Khodro sedan pulls up alongside. The scarfed woman driver rolls down the window, and holds out a bowl of olives and pistachios to me. I accept, pop an olive into my mouth, and she makes the same offering to my colleagues. “This would never happen in America,” says one of my fellow travelers. The driver nods, smiles sweetly, and pulls out into the main street, a stranger vanishing into a strange and lovely and singularly hospitable land.

richard bangs: I traveled the width and length, and I can now say with authority, Iran has disarmed.

Leave a Reply