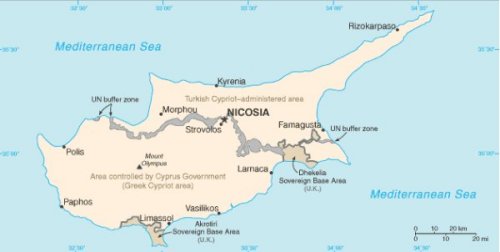

The first thing that drew me to Cyprus is that they are another of those countries that “doesn’t exist”.

The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is only recognized by Turkey itself. It’s also known as “North(ern) Cyprus”. According to the European Union (and much of the world), the whole island is one country. The reality of this is pretty clearly in dispute, as the TRNC runs its own border control at its (internationally unrecognized) various ports of entry. This all came about after the Turkish military came on the island in 1974 following a mess of events that year.

One of those ports of entry is Girne (Kyrenia), (North) Cyprus. That’s how I got in, via a ferry from Turkey.

Part One: The Turkish Cypriot

The first guy I met up with was a Turkish Cypriot whose family was originally from the south. They owned some shops in Girne/Kyrenia. He drove me around to different places in and around Girne, showing me a village that he particularly liked, which was basically Britain on Cyprus. Nice gardens on a secluded part of a hill. A shop had a sign in English informing its customers that they were going to eat the cost rise in beer, as opposed to passing it along to consumers. As I walked along, I was greeted by middle-aged white people saying “Hello”, not “Merhaba” (‘hello’, in Turkish). The guy told me that the Brits come there because it’s relatively cheap to buy nice places, as you don’t have to deal with European prices.

The first guy I met up with was a Turkish Cypriot whose family was originally from the south. They owned some shops in Girne/Kyrenia. He drove me around to different places in and around Girne, showing me a village that he particularly liked, which was basically Britain on Cyprus. Nice gardens on a secluded part of a hill. A shop had a sign in English informing its customers that they were going to eat the cost rise in beer, as opposed to passing it along to consumers. As I walked along, I was greeted by middle-aged white people saying “Hello”, not “Merhaba” (‘hello’, in Turkish). The guy told me that the Brits come there because it’s relatively cheap to buy nice places, as you don’t have to deal with European prices.

As we went around, the Turkish Cypriot and I talked about his sense of self. He said that he was Mediterranean. Not Turkish. Turkish Cypriot, sure, but there was a difference. He felt like he had more in common with people from Italy, France, etc. than he did with the Turks. He wanted Cyprus to be united, but blamed the Greek Cypriots for not agreeing to the most recent referendumon the matter.

We went to his friend’s cafe. They had grown up together in Girne and had known each other since the age of 2. As we drove back into the center of Girne, the guy waved and smiled to various people as we drove down the main drag. It was clearly his home, his element. Just a summer sort of a guy in a summer sort of a world.

He couldn’t host me, so I moved on to a Turkish guy, who also lives in North Cyprus.

Part Two: The Turk

The Turkish guy had been living in Cyprus for a bit. He was more than willing to talk politics as we went around more of the north, with no holding back on his critiques of American and Israeli foreign policy.

The first day, we went to St. Hilarion, a former castle made and run by the old French royalty that were formerly on the island. As it is high up with great views of below, it’s always been used for military purposes. And on the whole drive up, you see a base, with signs telling you not to take pictures.

All over North Cyprus, you see military bases. Apparently they used to be even more visible, with military vehicles being used inside the cities. I was never clear on whether the soldiers I was seeing were North Cypriot or Turkish. I’d assume a great deal of the latter, as the flags were Turkish. There are about 5,000 North Cypriot troops and 30-40,000 Turkish troops, for a northern population of less than 300,000. Occupation, from the world’s perspective. Protection, from Turkey’s.

Later in the day, we went to the other major city of the north, Famagusta. Aside from its walls, various imperial historical pieces, church converted into a mosque (above), etc., it has another oddity of the divided island.

The Ghost Town of Varosha

Varosha used to be the hottest part of Famagusta, which used to be predominantly Greek. After the invasion, it became military-occupied, off-limits to everyone else. Massive hotels are abandoned, falling apart. It’s a strange experience seeing a city that is just out of reach, perfect location, useless to everyone. I asked my guide why it’s still there. He winked and said “it’s just a card in the game”. That really creeped me out. To see any of this devastation as a game was a jaded perspective that I hope to never reach.

I knew that I was only seeing, at most, half of the equation. I was excited for my time with the next guy that I would meet, a Greek Cypriot.

Part Three: The Greek Cypriot

The Greek Cypriot is a moderator for various online Cyprus reconciliation groups. I figured this would make him a fairly impartial person. But his family story and personality made that impossible. This isn’t to say he didn’t *try* to see the other side, but personal history makes that impossible in these conflict situations.

Talking to him turned my prior experience on its head. His family was from Kyrenia, the place that I’d gone around earlier with the Turkish Cypriot. His family left in 1973 during the rise in violence before the Turkish incursion in 1974. He grew up in South Africa and returned to Cyprus a few years back, as his adopted country was in post-apartheid decline.

It was difficult talking to him at points because he obviously had spent a lot of time desperately trying to come up with what he saw as an objective solution, but clearly could not maintain objectivity. He would wrestle with himself on how best to deal with the issue in as fair a way as possible, but would always go back to his inevitable conclusion that the Turks were in the wrong and to blame for destroying what he thought of as a relatively peaceful place before the invasion.

Not long after I’d gotten into the south part of Cyprus, we headed back to the border as he showed me around Nicosia, the Cypriot capital. The Green Line, part of the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus, divides the Turkish and Greek parts of Cyprus. It used to be incredibly difficult to cross. Now, Cypriots (and most Westerners) can cross it as they wish. They barely seem to check when you go into the south (as they see it all as one island) and you have to go through a passport check and visa-on-a-separate-piece-of-paper-stamp for the North.

We stood and talked for a while on the Green Line (no, you don’t see an actual green line) in between the serious-ish TRNC border and the “look at your passport briefly, then wave you on” EU border. I’ll never forget having a loud conversation about Cyprus’ history and future in no man’s land, watching cats jump between abandoned buildings in a UN-controlled area (with no UN forces to be seen).

After our chat, we went back to his place, an apartment complex that was originally made for Greek Cypriot refugees from the north. Over in the distance, there was a hill on the north side of the island. It had a light show on it, wherein the elements of the Turkish flag would pop up, then finally end with the Turkish Cypriot flag, a mildly altered version of the Turkish flag.

Conclusions:

The views of the three, as I saw them:

— Turkish Cypriot: North Cyprus is not part of Turkey. It’s its own entity only because the Greeks didn’t agree to reunification.

— Turk: International affairs is a card game. You keep the cards to play them later. Turkey should maintain control of North Cyprus for that reason.

— Greek Cypriot: Cyprus is one country. The Turks are occupying the north. They displaced a lot of people and destroyed the relative peace between the two groups.

Cyprus solidified for me how difficult these situations are. It takes a really strong desire for reconciliation to fix something like this. For a couple generations now, the island has been divided. The Turkish Cypriot grew up in the north. That’s his home. Yet, for the Greek Cypriot, that’s his home, too. The home of his parents and family. The Turkish Cypriot goes around Girne and feels comfortable. The Greek Cypriot sees the place that his father proposed or where his grandmother died and feels sadness, a longing for a home he never got to grow up in.

The one thing that I left out of all of this is the involvement of powers beyond the parties themselves. Cyprus used to be a British colony. The British still have a military presence on decent chunks of the island, with the Americans maintaining a presence, as well. With its proximity to the Middle East (Larnaca to Beirut is a 40-minute flight), it’s a strategic location. So don’t expect the international community to stop having a vested interest. But how much they can do depends on the Cypriots themselves. From the couple of guys I met from either side of the Green Line, it seems like a lot of Cypriots want to live together. I hope outside parties will work toward that or stay out of the way so they can do it on their own.

All pictures can be found at flickr.com/roniweiss

Leave a Reply