Too vast. My eyes have nothing to rest on, sliding over rolling landscapes. With no point to hold my gaze, I’m afraid of tripping over the horizon. The road doesn’t look like it was designed to lead anywhere but merely to serve as a metaphorical symbol of the journey into the unknown.

Too vast. My eyes have nothing to rest on, sliding over rolling landscapes. With no point to hold my gaze, I’m afraid of tripping over the horizon. The road doesn’t look like it was designed to lead anywhere but merely to serve as a metaphorical symbol of the journey into the unknown.

There isn’t much to know in the unknown, it seems. It looks unfinished and bare. Only in places the ground is covered with withered grasses, sometimes leafless shrubs. That’s about it. It’s been a while since we saw the last cow. Or statue. Or dilapidated industrial or military building of unknown purpose. It’s been a while since we saw anything breaking the monotony.

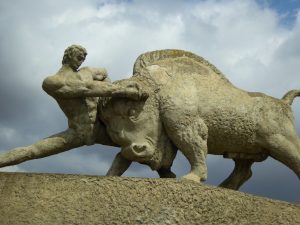

It started with crumbling asphalt giving way to a dirt road. On the left statues, on the right cows. The yellow-brown plains seemed to be pastures, because once in a while we would pass a flock of sheep. Then there were occasional concrete monstrosities of what looked like a metal shredding plant, then a power plant. Then even those gave way. The statues disappeared next; the last vestiges of civilisation. Huge, brutalist, weathered, they stood on the sides of the road, guarding the passage to nowhere.

For the first time in my life I’m in a foreign land without knowing where I’ll spend the night. But that’s a problem for later. Now I have literally a more pressing one. But there is nowhere obvious to stop; both sides of the road now covered in thick tangled mass of weeds and shrubs.

But we stop. When we get out, it only gets worse – both the biological and existential pressure. I suddenly become very aware that we’re the only vertical objects that can be seen around, standing on and standing out from flattened horizontal surfaces. If IKEA were assembling landscapes, this half-desert of Kakheti, a region of Eastern Georgia was left half-unpacked from its flatpack.

The guys start to piss, one by one, standing on the edge of the road, facing the vastness and pissing on it, knowing that mother nature can’t detract them from their direction. Lords of the wild, surveying the landscape offhand, cock in hand. They left the civilisation, the need for decorum. Me and A. – the only other girl – look at each other. This is not an option.

You go away, you hide in the bushes, squatting low to the ground, feeling like an animal; not to be seen, not to be noticed. Hurried, threatened, uncomfortable. We’ll go then, venture deeper into the wild. But most of the shrubs are not even reaching above our knees, so we’ll have to go further, 40 paces of so down the gentle slope toward a clump of bigger bushes. But even the first step off the road proves problematic. The desiccated shrubs have barbed stems or prickles, and after a few steps our trousers are covered with some round weed seeds; their surface covered with hooked hair that clings to fabric. I get annoyed that the call of mother nature gets interrupted by mother nature. We stop. The heat envelopes us, the sky is now clearer blue but leaden in its heaviness, thick air pressing hard on everything beneath it. I can imagine the landscape was once completely flat and even, but the constant pressure from above crinkled it into undulating plains. Another careful step, more of brittle twigs crushed under my foot.

You go away, you hide in the bushes, squatting low to the ground, feeling like an animal; not to be seen, not to be noticed. Hurried, threatened, uncomfortable. We’ll go then, venture deeper into the wild. But most of the shrubs are not even reaching above our knees, so we’ll have to go further, 40 paces of so down the gentle slope toward a clump of bigger bushes. But even the first step off the road proves problematic. The desiccated shrubs have barbed stems or prickles, and after a few steps our trousers are covered with some round weed seeds; their surface covered with hooked hair that clings to fabric. I get annoyed that the call of mother nature gets interrupted by mother nature. We stop. The heat envelopes us, the sky is now clearer blue but leaden in its heaviness, thick air pressing hard on everything beneath it. I can imagine the landscape was once completely flat and even, but the constant pressure from above crinkled it into undulating plains. Another careful step, more of brittle twigs crushed under my foot.

We’re maybe five paces from the road when we notice an old grey car coming closer, dust billowing around it. To make things worse, it slows down when it passes the guys and our parked jeep and then stops completely when it reaches me and A. You must be kidding me. Two men get out in a hurry and start shouting at us in Georgian, pointing at something, agitated. Or is it Russian? We have no idea what’s going on. Their message doesn’t sound hostile but it sounds urgent. And then they start hissing! I think I recognise one word, they keep repeating one word between the hisses.

Змея [zmeya]. There is a very similarly sounding word żmija [shmeeya] in Polish. Viper.

We wave something that’s supposed to mean we’re ok as well as mind your own business; if we want to piss on snakes, we’ll piss on snakes. But we start retreating toward the dirt road nevertheless. They drive away. We don’t have much choice; this landscape looks empty only to the naïve; those who know the land know it to be filled with sunbathing snakes.

Nature’s not my friend. It doesn’t want to be. You stay on the road, she says, stay on the dirty scar you made on my surface, and only there, little humans. So we do. A. and I start walking along the dirt track, so that we can be hidden behind the crest of the slope. We’re not hidden from anything, really; we’re still in the middle of an exposed road in an exposed land. We’re hiding for comfort, tricking our minds into thinking that if we can’t see anyone, not even our own car, then we have privacy.

We slide trousers down to the knees and squat, naked arses hovering over dirt. It doesn’t help knowing that I don’t think the vipers were informed about this unwritten social contract – humans keep to your road, snakes keep to yourself. I expect something to slither between my legs any moment and bite me in the arse. Unmetaphorically speaking. I keep listening for another incoming car and I don’t really feel like I need to pee anymore, but after all the hassle I feel like I should. It dawns on me I’ve put myself in this situation and this is how road trips are like. And that now I need to somehow reconcile the part of my self who likes being on the road, or likes the idea of being on the road, with the part of my self who doesn’t like pissing on the road. Or on snakes.

We slide trousers down to the knees and squat, naked arses hovering over dirt. It doesn’t help knowing that I don’t think the vipers were informed about this unwritten social contract – humans keep to your road, snakes keep to yourself. I expect something to slither between my legs any moment and bite me in the arse. Unmetaphorically speaking. I keep listening for another incoming car and I don’t really feel like I need to pee anymore, but after all the hassle I feel like I should. It dawns on me I’ve put myself in this situation and this is how road trips are like. And that now I need to somehow reconcile the part of my self who likes being on the road, or likes the idea of being on the road, with the part of my self who doesn’t like pissing on the road. Or on snakes.

They taught us—it was one of the first lectures in anthropology—they taught us about this cliché nature-culture distinction; how we tend to imagine nature as wild and female, culture as male and in control. It doesn’t feel like a cliché now though, and on my way back to the car I keep enviously ruminating on penises and hotels. I look at A. She gets it.

Leave a Reply