In Plovdiv, Bulgaria, John M. Edwards snitches on the mystery-shrouded Balkans’ best-kept secret: an ancient (and enduring) heresy

In Plovdiv, Bulgaria, John M. Edwards snitches on the mystery-shrouded Balkans’ best-kept secret: an ancient (and enduring) heresy

I was on the way slow train from Budapest through the Balkans, on my way to Bulgaria, chainsmoking and guzzling Egri Bikavier (Bull’s Blood) wine, when the train came to a juddering halt and was boarded by heavily armed Serbian soldiers.

A Serb with an impressive handlebar moustache and an assault rifle demanded my passport.

“Americansky!” The Serb spat. “You must get off train!”

Knobby knees buckling, I asked, “The train won’t leave without me, will it?” With all the seething political turmoil in the ex-Yugoslavia, I was seriously creeped out. I hoped this wasn’t an internment center or refugee camp.

“You must get Serbian visa!” he announced officiously. He rattled off something in a Cyrillic alphabet soup to his comrade, then briskly led me off the train. I knew I should have taken the more roundabout route through Romania rather than Yugoslavia. But for this to be a true trip through the Balkans I had to take the more direct path.

Inside a wooden shack, resembling an outpost entrance to a concentration camp, they interrogated me.

“I’m going to Bulgaria, not Serbia, “ I assured them.

“Why are you going to Bulgaria?” the moustached man asked, eyeing me suspiciously.

I didn’t want them to think I was a spy, or, even worse, a reporter. Instead of saying, Because it’s there, I said, “Uh, for vacation.”

They burst out laughing. The sinister border guards seemed amused I was taking a “vacation” in Bulgaria. They let me back on the train, but not in on the joke. They obviously knew something I didn’t. Judging by their somewhat misplaced laughter, I really had no idea what was in store for me in Bulgaria. Destination: Plovdiv!

* * *

The blond-haired, blue-eyed Moslem resembling Bruce Chatwin going native stood defiantly, playing the Rhodope bagpipes in the square, its sad wail reminiscent of the ululations of the muezzins who were rapidly disappearing throughout modernizing Bulgaria. He was a Pomak, an ethnic Slav Bulgarian whose family had converted to Islam under Ottoman rule.

But now Bulgaria is a staunchly Orthodox Christian country, but like all Balkan nations, it had its fair share of Moslems and Gypsys who hadn’t quite integrated under the former communist government’s enforced “Bulgarization” program. This is just an example of a paradox in what could be the dizzying Balkans’ most puzzling jigsaw piece.

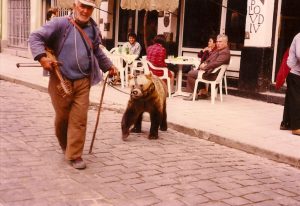

Well off the beaten European tourist trail, Plovdiv had a lot of remnants of the past to recommend it. There was a gorgeous Ottoman mosque, as well as Roman ruins—and, too good to be true, even older ancient pre-Greek Thracian ruins. The place did indeed have a magical, almost Orphic atmosphere. Over there a Turk unrolling his prayer mat in the marketplace, over there a man leading a trained bear on a leash, and over there a midget in evening clothes waiting tables at a restaurant.

Well off the beaten European tourist trail, Plovdiv had a lot of remnants of the past to recommend it. There was a gorgeous Ottoman mosque, as well as Roman ruins—and, too good to be true, even older ancient pre-Greek Thracian ruins. The place did indeed have a magical, almost Orphic atmosphere. Over there a Turk unrolling his prayer mat in the marketplace, over there a man leading a trained bear on a leash, and over there a midget in evening clothes waiting tables at a restaurant.

It felt like I had jumped into a Tintin comic. Surely Bulgaria must have been the inspiration for the mythical kingdom of “Syldavia” that Tintin visited in King Ottakar’s Scepter? The only other things I knew about Bulgaria were that Georgi Markov, a Bulgarian defector, was killed on London Bridge in broad daylight by being casually poked in the ribs with a poison-tipped umbrella, and that Bulgaria (“Vulgaria”) was the setting for the evil baron who hated children from Cubby Brocolli’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!

Built over an ancient Thracian site, Plovdiv was called Philippopolis when it was founded in 342 B.C. As I walked around the lower town I noted the Byzantine walls, Roman columns, and Ottoman minarets. The Hisar Kapiya (Fortress Gate) was built back in the times of Philip II of Macedon: a trace of Thrace.

At last walking into the Stariyat Grad (Old Town), I couldn’t believe how picturesque were the 19th-century timber-framed mansions almost coming to loggerheads on the narrow cobblestone streets like a fantastical setpiece for a German Expressionist film (Bulgaria’s ex-ruler King Boris, who really did resemble Boris Karloff, was actually German)—all the product of the so-called Bulgarian Renaissance. Amid this stunning Balkanesque backdrop were more people than the city could hold: I had arrived in the middle of an international trade fair, the largest in the Balkans. Said a dodgy Brit with bad teeth in for the fair, “The fair is great, mate; my trade is ‘pharmaceuticals.’”

Joining the “korso” (evening promenade) down Ulitsa Knyaz Aleksandar I, I set off to uncover a restaurant, any restaurant. Although most of the eateries were full of trade-fair revelers, I finally landed at a table outside a small dump on a sidestreet. I wondered why the eatery was almost empty. I also wondered why such a beautiful city was almost unknown. With a little renovation we had another undiscovered Prague or Talinn, albeit with a different architectural legacy, on our hands.

After waiting an hour for my Bulgarian grub (tripe soup!) I was steaming mad. I should have just gotten some fresh yoghurt and baklava (both purportedly Bulgarian inventions) at the outdoor marketplaces. When my lukewarm “special” resembling cannibalism and locally produced red wine finally arrived, I remarked on the poor quality of both to the dwarf waiter, and I asked for the bill.

“The wine eez wery special,” the dwarf explained in a piping castrato voice, as I eyed the bill, featuring a hefty markup. I’d heard of this before: a simple case of a menu switch.

Nah-un, no way.

After arguing about the bill for several minutes, the dwarf ran back inside and got the Bolshevik manager, who, believe it or not, was wearing one of those big bulgy Chef Boyardee hats. He yelled loudly at me in Bulgarian. I felt like I was in one of those Tony Curtis “Great Race” movies, facing the villain with a pencil-thin Cantinflas mustache, or any flick with David Niven.

I refused to be extorted.

Out of nowhere rushed two youngish travelers, looking very Lonely Planet, saying, “Hey, what’s all the trouble?” An American with a Midwestern accent, who was teaching English in Plovdiv, expertly negotiatied in cutting down the bill somewhat, as I noted the strange Bulgarian mannerism and custom of nodding the head no and shaking the head yes. An inexplicable conundrum. Which made it hard to follow the course of the convo.

Finally, it was all hearty guffaws and “blagodaryas” (thankyous) all around. Then I left with the American and his Bulgarian sidekick and went to the amazing almost-perfectly-preserved Roman ampitheater to sacrifice a bottle of Bulgarian red in the moonlight. One of Bulgaria’s early rulers, Khan Krum, used to drink wine out of his enemies’ skulls, I remembered reading somewhere. Probably better and more hygienic than passing around the bottle. In the moonlight, among the ruins, the American said, “I can tell you’re different. . . .”

I had been a houseguest of the American and Bulgarian for several days, when the American (name withheld) hinted that he may or may not work for a well-known intelligence-gathering company usually referred to by three letters. CIA or KGB? Probably to prove he was a real American, not just a pretend spider, with evident hilarity the American sang an old jingle from tlevision: “Who’s the kid with all the friends hanging round, kid with a snowman, Snowcone!” In retrospect, he resembled Bulgarian-American Cult Leader David Koresh, and maybe it was him? He also offered to take me on a tour of the legendary Bachkovo Monastery.

I had been a houseguest of the American and Bulgarian for several days, when the American (name withheld) hinted that he may or may not work for a well-known intelligence-gathering company usually referred to by three letters. CIA or KGB? Probably to prove he was a real American, not just a pretend spider, with evident hilarity the American sang an old jingle from tlevision: “Who’s the kid with all the friends hanging round, kid with a snowman, Snowcone!” In retrospect, he resembled Bulgarian-American Cult Leader David Koresh, and maybe it was him? He also offered to take me on a tour of the legendary Bachkovo Monastery.

“Christianity in Bulgaria is a little different,” the Bulgarian offered sotto voce, a mysterious smile parting his beard. “It’s a kind of mix Christianity and Paganism!”

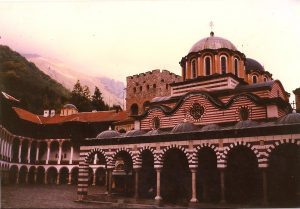

With this in mind later the next day, I accompanied the American on a series of bus rides, filled with Universal-Pictures-like Gypsys wearing outlandish garb, until we found ourselves at the beginning of a wide valley leading to Bachkovo, founded in 1083 and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

After tramping a while, I asked if we could head back. There was something strange about the vast valley that gave me the willies. We stopped and the American found a stone sculpture that he had made and left behind on the trail on a previous trip. He commented, apropos of nothing, “Did you know that some people think [Eastern Orthodox] monks can walk straight through mountains?”

And so we began to go uphill.

We came across a small fountain for washing our feet.

We ran into some other pilgrims walking the shining path, their icon eyes blazing. They said something to us. The American translated for us, “The Truth!”

Entering the monastery through a door leading into a cobbled courtyard, we saw some frescos depicting the torments of hell. At the nearly right-there Sveta Bogoroditsa, a church built in 1604, we admired the transplanted Georgian icon of the Virgin, which the American said with demonic cheer, “Looks like it’s from outer space, doesn’t it?”

Indeed, all the Byzantine Empire mosaics and frescos had figures with numinous golden-halo helmets and otherworldly pagan bespoke robes. On this day, black-clad Bulgarian monks swung censers to “drive away evil spirits.” On the walls I noticed little eyes in pyramids, which many believe are Masonic symbols. The Cyrillic alphabet was invented somewhere in these parts by the Bulgarian monks Cyril and Methodius, and is still used in many places today, such as Russia. At times resembling a mirror-image of Latin, the Cyrillic Alphabet sometimes is almost decipherable: Bulgarian “BAP” means “BAR,” for example.

After admiring the ancient witchcrafty church, we took a lengthy hike to reach a remote chapel, which would have been impossible to find without the American as a guide. Going up a steep hill we came across an old picture of Christ in a cracked glass frame, then went on up the hill to yet another chapel farther up the mountain. On the way I noticed little bits of rags tied to the branches of trees.

“What’s that for?” I asked.

When an old babushka crone came out of nowhere—yes, cackling.

“The Baba, the Baba!” the American laughed cryptically, as she ascended the hill with her gnarled wooden cane. “A witch!” He whistled.

At a chapel on the edge of time, the American led me inside: “There’s something I want you to see.” Inside, there was an ancient Christ Pantocrator approximating a peace sign painted on the ceiling and a prayer niche with a velvet curtain in front of it.

“Can I borrow your camera? There’s something scary I want you to see!”

He shot a photo into the recess, and there was a bright flash!

Hence, the Manichaean fresco was thus illumined.

What the?!

I have to admit I was very startled by what I saw. You have to go there yourself to see what it is. Let’s just say, there was an ancient heresy in Bulgaria called the Bogomils (circa 10th century), who believed the world was created not by God but by Satan. . . .

* * *

Back in town at a Thracian excavation site, we puzzled over why there was no one to protect the ruins from plunderers, including us. The Thracians, who practiced an orgiastic free-love religion linked to the Greek god Dionysus, were skilled archers and equestrians. One group called the Capnobatae (“Smoke Treaders”) got high on hemp seeds—the ancient world’s first hippies. I carefully arranged a pile of ancient Thracian phalluses, an archaeologist’s wet dream, and snapped a photo.

I was really digging Thrace.

“You can take some if you want,” said the American. “Except they’d probably confiscate them at the airport.”

Grabbing a phallus as a souvenir and inserting it into my daypack, I had for the first time in my life become an amateur smuggler. (But if you fink on me and tell anybody, I’ll claim it dropped out of my bag on the way to the train station.)

Right before I left Plovdiv, while boarding the train to Instanbul, I noticed a tour group of people wearing T-shirts emblazoned with “Florida Friendship Front.” I pointed this out to the American, who laughed, “Let’s see, FFF”—a David Letterman-like smile creased his face—“So F is the sixth letter of the alphabet, so 666, the number of the Beast!” Everyone laughed uproariously. Way clever, yes, even genius, but I have to admit I was also a little spooked. I hoped the train didn’t have some secret ulterior destination I didn’t know about yet, such as Danté’s Inferno.

I boarded the train, waved goodbye, and settled into my compartment.

And off went the train.

Somewhere in European Thrace, there was a sudden crash!

On impact I went flying backward in my cabin. The bunk above my head slammed down off its hinges like an accordion in a crowded beerhall.

Or, a Balkan Jack-in-the-Box.

I would have been killed had I not been thrown backward.

Wow, the train had hit a truck and was now derailed!

Thanking my lucky stars to be in one piece, I got off the train as Turkish workmen grimaced, ran around like maniacs, and dangerously smoked cigarettes near leaking oil. Nobody seemed to know what to do.

It was a fitting end to my mysterious little trip through the Balkans. Eventually a battered dolmus arrived and I pressed in like Jim Morrison, a big fan of Orpheus, breaking on through to the “other side,” headed for Instanbul, the ex-Constantinople, sort of lost with my secret (and stashed phallus) in the Turkish part of European Thrace, in the place where Europe ends and Asia begins. . . .

Leave a Reply