As you look down from the hillside onto the apparent perfection of Malta’s Blue Lagoon, you struggle to imagine it in any other condition. Land embraces lagoon like a protective parent. Water shines like a molten blending of sapphires and emeralds. The perpetually cloudless sky appears hazy against such brilliance. Craggy islets guard the entrance like dorsal spines on some mythic leviathan. But you walk the Malta of the modern world, a Mediterranean archipelago where prehistoric temples, safely preserved within the womb of nature for millennia, are being eroded in less than a hundred years by pollution, vandalism, and the very air we exhale.

As you look down from the hillside onto the apparent perfection of Malta’s Blue Lagoon, you struggle to imagine it in any other condition. Land embraces lagoon like a protective parent. Water shines like a molten blending of sapphires and emeralds. The perpetually cloudless sky appears hazy against such brilliance. Craggy islets guard the entrance like dorsal spines on some mythic leviathan. But you walk the Malta of the modern world, a Mediterranean archipelago where prehistoric temples, safely preserved within the womb of nature for millennia, are being eroded in less than a hundred years by pollution, vandalism, and the very air we exhale.

Who cares about a bunch of rocks? The majority of Maltese seem to care very little. Hunters consider the temples an obstruction and use the fragile stones for target practice. Lovers seek to immortalize their union by painting or scraping their initials onto the ancient surfaces. Even you, who consider the temples sacred, damage these walls with your presence. Each breath you expel adds to the gradual erosion of the stones. Still, you can’t help but applaud the slow-moving wisdom of the government. They may close all the temples tomorrow, but you’re seeing them today.

Then you realize that the damage extends far beyond the confines of the temples. Remnants of the human presence-chip bags, cigarette packages, and condom wrappers-litter roadsides and line the low stone walls of the countryside. A shiny black snake, barely a centimetre across, slides along the base of one of those walls. The fledgling leviathan sidles around an immovable juice bottle, then darts back to the wall, back to its meagre shelter from the noon sun. Legend holds that St. Paul robbed the island’s snakes of their venom. Nature retaliated by placing the venom in the tongues of women. Even miracles lack surety. Most changes, even for the good, come with a price.

Malta’s history is a study in change. In the centuries before becoming an independent republic in 1974, Malta played host to a series of conquerors and protectors. The archipelago’s beginnings vanished in the fog of pre-history, but hints remain as to the nature of life among the ancients. Temple builders, they dedicated their lives to the fertile earth. By their own reckoning, both they and the temples came from the earth and returned to it in death. One might claim that Ggantija-one of the few surviving temples-is older than God. It certainly predates the pyramids at Giza by roughly a thousand years, making it the oldest freestanding structure yet unearthed.

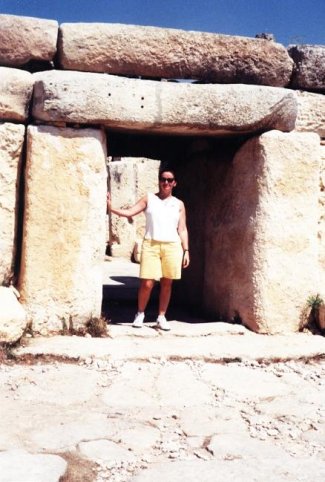

Walking within the walls of Ggantija-or any of the temples-becomes a tactile experience. Touch the stones. Warmed by the sun, they seem alive with energy. Let your fingers play over the weathered texture, the spiral designs tracing the renewing cycle of life. Imagine them smooth with newness and the ceiling rebuilt. Let yourself slide into the role of priestess. Bless the children born of woman’s fertility. Bless the harvest born of the Earth Mother’s fertility. The serpents need not hide. They spin in circles, chasing their tails. More than mere aspect, they embody the design itself. Life starts and ends, and starts again.

Walking within the walls of Ggantija-or any of the temples-becomes a tactile experience. Touch the stones. Warmed by the sun, they seem alive with energy. Let your fingers play over the weathered texture, the spiral designs tracing the renewing cycle of life. Imagine them smooth with newness and the ceiling rebuilt. Let yourself slide into the role of priestess. Bless the children born of woman’s fertility. Bless the harvest born of the Earth Mother’s fertility. The serpents need not hide. They spin in circles, chasing their tails. More than mere aspect, they embody the design itself. Life starts and ends, and starts again.

Step back farther and see the ancient Mediterranean world, a vast, verdant continent-no Maltese archipelago, no Sicilian island, no Italian peninsula. Then the ocean rose, fracturing the land and exposing Malta like an unwanted child.

In modern times, garbage cuts a jagged path into the sea. Some items float on the surface, giving a hint of the damage that rests below. Even the Blue Lagoon, a favourite retreat among tourists and locals alike, bears the scars of abuse. You can’t see them at first. The illusion of perfection holds too great a power.

Look over the rail of the tour boat. First you notice the clarity of the water, then the way the white sand bottom seems to reach up to the sun. Slim black fish, no more than three inches long, swim by in oblong schools like passing storm clouds. You take a few pictures to capture the images for others to see. Then you simply stare, letting the images develop in your memory.

A flurry of motion attracts your attention. The fish congeal into a pulsing mass, as if forming one creature. A flash of red and brown marks the centre. The predators have found their prey: a discarded candy bar wrapper. Each quivering attack sends the slick paper spinning. Only when they’ve picked the last of the brown meat from the white interior does their frenzy end. A lone fish breaks formation and approaches a new offering bobbing a few feet away. Like a tentative lover, it touches its lips to the morsel. Has it tasted nicotine before? One would think so, given its hasty retreat. No other fish repeats the experiment.

Malta, like so many modern cultures, feeds upon itself to prolong its existence. Honey-yellow limestone forms the core of the archipelago. When first quarried, the stone succumbs easily to the workers’ tools. Exposure hardens the stone until it’s as durable as concrete. Once used in the construction of temples, the stone now serves for everything from bridges to bus stops.

Malta, like so many modern cultures, feeds upon itself to prolong its existence. Honey-yellow limestone forms the core of the archipelago. When first quarried, the stone succumbs easily to the workers’ tools. Exposure hardens the stone until it’s as durable as concrete. Once used in the construction of temples, the stone now serves for everything from bridges to bus stops.

Meanwhile, the quarries seem to scream their pain and rage skyward. They’re meant for conversion to farmland, but truckloads of landfill and topsoil can’t keep pace with excavations. As the tour bus passes yet another crater, your guide smiles and assures you that there is enough limestone for at least two hundred more years of quarrying. The implication seems clear. Any event that will not occur during one’s lifetime warrants minimal concern.

You can’t help feeling grateful for your chance to experience a few of Malta’s natural and constructed wonders. Reborn temples stake a sacred claim on the land and on your imagination. But upon each memory of grandeur, a corresponding sense of loss intrudes. The images stay with you: waste-devouring fish, polluted lagoons, eroding temples, and disembowelled earth. How much longer, you wonder, before Malta collapses in upon itself and litters the Mediterranean with its remains?

The future teeters on the present. If you could travel forward in time, what might you see? Perhaps nothing more than a single black snake, coiled within the arc of a floating juice bottle.

Leave a Reply