In the eager pool of morning light there rises The Rock. It is perhaps the most iconic symbol of the implacable indifferences of inhospitable landscapes, its dimensions timeless, unsummarized.

In the eager pool of morning light there rises The Rock. It is perhaps the most iconic symbol of the implacable indifferences of inhospitable landscapes, its dimensions timeless, unsummarized.

And I want to climb it.

There is something in the Western mindset that arouses a near irresistible urge to climb a peak. We look up, we admire, and if possible, we act. It may be related to a primal impulse to conquer a headland, to be king of the hill, surveying all below. And so we tread upwards, by sandal, sedan chair, boot, crampon, funicular, escalator, elevator, téléphérique, gondola, train, whatever — resistance is futile. The summit result is a near narcotic of validation, accomplishment, exhilaration, pride and joy, coupled with a grand view.

Uluru, née Ayers Rock to those of a Western bent, beckons, it cries to be climbed. It has dark water stains streaking down its sides, looking like tears. I first leaned towards its astonishing red face while watching a 1978 John Denver special, in which he performed on top of The Rock. Wow. What it must be like to up there, with all the world spread below.

I’ve ascended hills and mountains around the world. Yet now, I am at the base of the famous inselberg, watching dots of people making their way up the chained scar-like path to the mighty view.

But, I am not doing that.

The airline counter woman in Sydney, when she saw the ticket to Ayers Rock, said, “Oh, you have to climb The Rock. It is fabulous!”

But, I am not doing that.

When the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was handed back to the Anangu Aboriginal tribe in 1985 one of the conditions was that the climb remain open. It’s popular, and brings touro-dollars to the region. But that doesn’t prevent the Anangu from posting signs and making personal pleas urging visitors to stay at the bottom. Even the entry ticket to the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park entreaties to not do the climb.

And so against instinct and aspiration, I vow to not do the climb. And that decision liberates a different level of awareness and adventure, it pricks the pleasure zones that come from restraint, reflection and respect. Yes, I can forgo the physical overthrow and instead climb a spiritual plateau. But I have the itch to move, and so discover a whole host of alternative things to do here in the Red Centre of Australia.

I begin with a sail on a ship of the desert. It turns out there are more wild camels in Australia than anyplace in the world. They were imported in the 19th century from the Afghanistan region to help lay the telegraph line that would connect the antipodean to the world. They helped lay the first rail ties. But they built the tracks to their own obsolescence, as with trains and roads they were no longer needed, and the government asked the Afghani cameleers to kill the beasts. They refused, and the camels went feral. Today estimates vary from 500,000 to a million camels on the loose in the Outback.

I arrive at Uluru Camel Tours to the sounds of old men snorting and humphing — the 60-some camels out back are grazing some sere scrub before the next ride (“Book early for a good looking one,” says the brochure.) They are very tall, with impossibly long and knobby legs and a cavalier look. Mark Swindells, the co-owner, ushers me to Daisy. Mark instructs Daisy to kneel, her front legs doubling over until they touch the ground. I throw one leg over her arched back, and grab the pommel bar with both hands.

Daisy makes a sound like a Wookie, then does her boat-rock rise, and I look down at her feet. They are big, round, splayed and padded, swollen looking, soft and squishy, like giant cat paws without the nails.

Daisy makes a sound like a Wookie, then does her boat-rock rise, and I look down at her feet. They are big, round, splayed and padded, swollen looking, soft and squishy, like giant cat paws without the nails.

We turn by the spinning sails of the wind-pump and head in the direction of Uluru. Daisy gaits along with no hint of hurry, even though this is rush hour in the Outback. Back home, in Los Angeles, at this hour I am often stuck in traffic, choked not merely with pollution, but with the emissions of haste, rage and cell towers. Here there is none of that nonsense.

At one point Daisy curves her long neck back on itself and we exchange glances; she almost seems to be flirting with her glistening bulb-eyes…I can’t help but notice she seems to have large French eyelashes…quite seductive…. but British teeth.

We pause on a hill to watch the sun set fire to Uluru, and after a time Mark says it’s time to return. With her saddle creaking, Daisy lashes me back and forth in a movement a bit like Latin dancing as we gambol down the hill.

I stay at the Aborigine-owned Sails in the Desert Hotel, a full-service resort that springs like an oasis from the soft rufescent sands. But it’s an early tuck-in, because the first light can’t be missed in these parts.

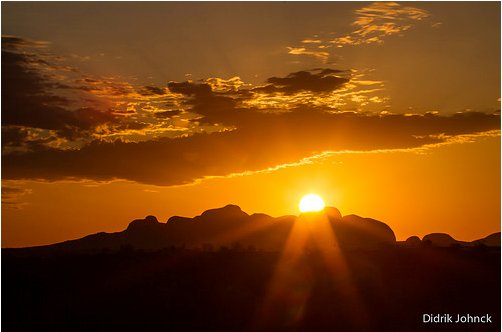

By 5:30 am I’m at the viewing platform on the western side of Kata Tjuta, slapping my upper arms, wishing I had brought warmer clothing. But thoughts of the cold evaporate as the first rays of light steal across the unretouched desert and begin to paint the collection of 36 sandstone beehives. I begin to feel something prickly and wonderful happening to my skin: horripilation. The domed rocks start peacocking, colors spreading from pink to burnt orange, blood red to desert yellow. It is easy to see why this is a chthonian place for the Anangu.

After the rock and awe it’s time for a billy tea and freshly baked beer bread. Then over to the Maruku Arts Centre, where I meet an elder Anangu artist, Alice Wheeler, and her friend, Geraldine Anton, a French student apprenticing here for the past couple years. Alice swipes her hand through the sand to demonstrate how the Aborigines, one of the oldest human societies on earth, who have no written language, would tell their stories and preserve their history through symbolic art. The rendition is all from an aerial perspective, as though seen from the top of Uluru, and so I ask, why should we not attempt this view? She refuses to answer, shakes her head in a scowl. Geraldine steps in, “Information and knowledge have to be earned.” I am scolded to be in the real time of art creation.

Then she moves under an awning, and spreads a large parchment on a flat surface. A travelling easel salesman would not do well here. Alice proceeds to create a new piece, this filled with pointillist renderings and ideograms. I ask the meaning, and she gives vague references to singing the universe into being in a tryst of cosmopoiesis. She references Creation Time, songlines, dreamtime and totem animals. Later, I am told that the dot painting is a method to hide the real meaning of the Aborigine art from outsiders, from the uninitiated. Visitors are just given a children’s level of detail. No obol to Charon could get me across this river. The art here is in the unknowing.

Then she moves under an awning, and spreads a large parchment on a flat surface. A travelling easel salesman would not do well here. Alice proceeds to create a new piece, this filled with pointillist renderings and ideograms. I ask the meaning, and she gives vague references to singing the universe into being in a tryst of cosmopoiesis. She references Creation Time, songlines, dreamtime and totem animals. Later, I am told that the dot painting is a method to hide the real meaning of the Aborigine art from outsiders, from the uninitiated. Visitors are just given a children’s level of detail. No obol to Charon could get me across this river. The art here is in the unknowing.

As the evening light rakes across the bush I head over to a place called Tali Wiru (beautiful dune), which, with a backdrop of Uluru (almost anywhere you go for kilometers in any direction offers a backdrop of Uluru), serves up a table d’hote four-course dinner that spills into the starry darkness. The menu includes such as native thyme and garlic grilled darling downs wagyu fillet, wattleseed rubbed kangaroo carpaccio, bunya nut and shallot crusted polenta fondant and bush yoghurt foam, all paired with fine Australian wines. Between the main courses and dessert a waiter appears with a laser pointer and travels the sky, from the Southern Cross to Scorpio to Orion, all riding beneath the dense swath of the Milky Way. Then we retire to a campfire and listen to the dulcet tunes of a didgeridoo, which sounds not unlike the raspberry blowing I did at school, but with a trace of melody.

Up again insanely early the morning next for the benediction view, sunrise over Uluru. Even though there are hundreds at the viewing site, I feel this is Earth’s first dawn. I always assumed Peter Lik used filters for his brilliant photos of The Rock, but no need, it appears. No dye, no tint, no coat of thin blood could make this scene more vivid. It is so dunning it precipitates mad ideas of ascension, pulling my thoughts upwards into spirals. Who could resist?

As with many mountains there is a summit book to sign. But this register, near the base of Uluru, is for those who choose to not make the climb. I sign with a strained flourish.

Denni Russell is my guide, a superbly knowledgeable escort, and she leads me to the edge of Mutitjulu Waterhole, a semi-permanent watercourse nestled in the contours of Uluru. The water looks so cool and inviting as the day heats up, and I have this lust to strip and jump in for a splash. But Denni instructs this, too, is sacred, no swimming allowed, so again, the art is in the not-doing.

Some things are sanctioned, however. I spend an hour at the town square lawn re-learning to fling a curved stick. I had forgotten how to throw a boomerang…but it came back to me.

Actually, we learn that the boomerangs here do not come back. In the coastal areas the Aborigines devised a larger version with different aerodynamics so that the weapon, after clipping a bird, would not be lost in the water. Here, though, with the vast vacant landscape, there is no need for a return….just accuracy at 140/kilometers an hour to bring down a running supper.

The bush boomerangs are made from mulga, a hardwood acacia, and have as many uses as a Veg-O-Matic. You can scratch your back, make a fire, make music, employ as a cooking implement, a ceremonial object, a message stick, and you can hunt. A thought that works up an appetite.

I lunch in town, at Geckos, next to an Asian eatery with my favorite local name, “Ayer’s Wok.” As with most of the food here, it is tucker to table, or paddock to plate, and I dig into an Outback Pizza smothered with smoked kangaroo and emu strips.

Afterwards I sit down to watch the Wakagetti Dancers, who stage an animated performance that mimics various animals the Aborigines hunt in the Bush. Then they invite audience members to give it a go, and what looks noble, graceful and realistic when the Aborigines swoop and swirl, looks a little campy when we westerners attempt, but also undeniably fun.

So much of the Aboriginal interface is about not doing, curbing curiosity and transit, that it seems incumbent to do something in the Western sphere. Blaise Pascal said in The Pensées, “Our nature lives in movement; complete calm is death”…and so, I hop on a Harley with Uluru Motorcycle Tours, and unpack the thrill of rebel speed as we slice the warm air while an orange rim smolders the wide horizon. No doubt, there is a tension between spirit and speed here, as I can barely repress a yen to roar the bike overland towards the base of The Rock.

Nonetheless, I am not doing that.

That night it’s a self-cook indoor grill at the Pioneer Outback BBQ, a favorite among locals. Looking around the low-lit hall I think, for a fleeting moment, I’m in a cellar full of giant mushrooms. Virtually everyone inside is wearing a slouch hat; many the distinctive fur Akubra. It reminds me of my dad’s era, in post-war America when every middle-class man wore a wide-brimmed hat out of the house.

They wink at me, four locally-sourced sausages, kangaroo, emu, crocodile, and camel (the four food groups of The Outback), and a Wagyu rump steak, which I sizzle to well-done and then consume with two glasses of “150 Lashes” pale ale and awesome live music from Marc Lawson, the airport ground handler. By the time I get up to leave my belly is shaking like pudding.

The sky the next day is smooth, translucent, like the belly of a frog. I decide to make my way towards Alice Springs, capital of the Outback. It’s a five hour drive, a wink and a nod for locals…some will effort the distance to see a movie…but I decide to break it up with visits to Curtain Springs Station and Kings Canyon, the Grand Canyon of Australia.

Curtain Springs is a privately-owned million-plus-acre cattle station, anchored by one of those desert roadhouses that prides itself in its eccentricity. It sells bags of animal scat, (bull, kangaroo, wild horse, gecko, rabbit, camel, and emu …all that’s missing, says the packaging, is “political bull shit–the bags are not big enough.”

There are also bottles of Curtain Springs Fucking Good Port, (makes rabbits bite pitbulls, leadens pencils, bluntens barbwire, prolongs premature ejaculation, Flying Doctor fuel…) and pun-laden signs all over the place that would make a groan man cry. “A midget fortune teller escapes from prison—he is a small medium at large.”

Out back, cages of cockatoos are squawking like rusty hinges; out front, they serve the best camel burgers this side of Doha (and I’m told Qatar and the UAE import their camel meat from Australia).

From Curtain Springs I join a 4WD expedition out to Mt Conner, which looks a poor-man’s version of Uluru (often mistaken for The Rock when driving from Alice Springs, and called “Fooleru”). Its mid-day, so the mountain is drained of color and definition (“11 to 3, sit under a tree,” goes a local saying.) We stop at an inland salt lake to potter among the blinding grains, stepping over delicate little scrawls of tracks, and plucking saltified lizards from the pan. And then we go chasing wild red kangaroos bounding through the screens of spinifex.

Back at the ranch, we meet co-proprietor and real battler Lyndee Severin, wearing a shirt that says, “Every guest brings us happiness. Some when they arrive, some when they leave.” She shows me her latest enterprise: making paper out of the surrounding native grasses. With a grant from the territory, she’s set up shop in the abandoned abattoir, and goes through the elaborate process of feeding grass into a machine that pumps out pulp. She then sells the results as art paper to passing tourists.

I check into the Kings Canyon Wilderness Lodge, which is glamping at its best, safari-style air-conditioned canvas tents with king-size beds on wooden platforms in a grove of tall desert oaks. It offers all the accoutrements of a city five-star, but with the added thrill of snakes and dingoes outside.

Graham Wells is host of the hotel, and offers to lead a hike through the Canyon the next day….he’s been 80 times this year alone, and seems eager for more, but only after a strong cup of coffee.

The early morning hike feels a step back to original sin, traversing a cut into the George Gill Ranges, into the dry heart of Watarrka National Park, to a palm-lined garden called “Eden.” Graham reveals the geological recipe: “Take some sandstone, add wind and water, wait 20 million years–and voilà!”

We tramp a kith of stone, sand and sky. Unlike some on Uluru, I am a yank without a chain on the three-hour rim hike through rough country that could be the American southwest, but with monitor lizards, ghost gums and plants 60 million years old, postcards from the past, as Graham says. He shows us scallops in the sandstone, leftovers from the ancient inland sea, each ripple perfect as a baby’s fingernail. He points out the ipi-ipi plant, which he pronounces a caustic vine. The local aborigines, the Luritja, would punish the wrong-doers by dropping the poison from the ipi-ipi plant into their eyes, and setting them loose in the desert. If they survived, they were redeemed.

This is a hike that can cure any aching psyche. We traverse the edge of a precipice with walls cut by a butter knife. The Adventures of Priscila, Queen of the Desert, had its aerial denouement at the edge here. A 23-year-old woman tourist from Britain fell to her death this past summer, some say while skylarking at the brink. We lean the other way passing by.

It is such a lovely and rewarding hike that I decide to return by helicopter to get the high view. From the Robinson 44 it looks even more almighty as we sail up the canyons and around The Lost City, a disorder of weathered buttresses that look like the ruins of a mythic city, over the maze-like gorges that have cracked this land like an eggshell.

On the way back to base I see movement on the ground, but can’t quite make out what is rippling the spinifex. We make a lower pass; I see it is a herd of wild camels….with the ground the same color as their backs they are… camelflaged.

Back at Kings Creek Station I jump on a quad bike for a hooned-up ride down and around bleached desert paths, past the long-lipped faces of more wild camels, skirting vortexes of dust devils, and then back for a beer and a dust-off at the station.

Then it’s off to Alice Springs, the “Big Smoke,” red heart of the Outback. It was founded in the mid-19th-century as a repeater station for the telegraph line connecting Adelaide to Darwin. Years ago I read about a couple of events in Alice Springs–Henley on Todd, a boat race down a dry river bed, and a dwarf-tossing contest. That put the marker on my map. Not that I’m an advocate, but any town that could conduct such offensive silliness deserves a visit.

The drive through the Outback is like a meditation, a straight and quiet hum. I check into Lasseters, a relatively new resort and casino on the edge of town, and head for dinner at the Overlanders Steakhouse, smoking away in the middle of a range of galleries featuring Indigenous art. Inside I meet proprietor Wayne “Krafty” Kraft, who has kitted out his place with all sorts of knick-knacks from the days of “Drovers” (the Aussie cowboys who moved cattle), and movie posters of films shot nearby. By the bar is an Australian Bush Barometer, a string with instructions: “If string is wet, it’s raining; if strong is dry, it’s not raining; if string is swaying, it’s windy; if string is invisible, it’s night; if string is smoking, the place is on fire.”

Krafty hails from Adelaide, and made a pit stop in Alice Springs 42 year ago, and hasn’t yet moved on. He joins me for a Scotch fillet, and when mine is served, he points to a little flag sticking out of the meat and says brightly, “Congratulations!”

“What for?”

He now aims his fork forcefully at the flag, and I lean in and see it says, in small letters, “Well Done.”

Towards the end of the evening, over a wickedly sinful Australian Pavlova, Krafty honeys he has found his spot here in Alice Springs, which he purports is in the middle of everywhere. “There are beaches in all directions,” he boasts.

“But I thought you were just passing through?”

“I am looking forward to my next stop, which is likely nowhere never, because I like it better here.”

In the unlimited blue of morning I set out to explore a couple of the gems in town, the Alice Springs Desert Park, which features the various habitats and wildlife of the Outback, and the Reptile Center, which houses the huge Perentie Goannas (monitor lizards), Frill-Neck Lizards, Thorny Devils, and other lizards of Oz. There is a giant salt-water crocodile, and slithering gobs of snakes. Of the ten deadliest snakes in the world, twelve are here.

“The reptiles here eat everything you don’t like,” says Rex Neindorf, the founder, “spiders, scorpions, cockroaches, and Brussels sprouts.” Then he pulls from a cage an olive python, which wraps around his neck and torso as he calmly expounds, “A single rat will hold him for a week; a rock wallaby for three months….a tourist for six.” I groan like a goanna, and head down the road.

At the Desert Park I meet Damien Armstrong, an Aboriginal guide and local rock star, who agrees to answer some questions about why visitors should not climb Uluru. “It would be like our visiting the Sistine Chapel and climbing its steeples; it would be like abseiling down the side of The Vatican. Uluru is a sacred house for us, a dreamtime sanctuary.

‘But there is more. If you own a pool and a child drowns in it while you’re not around, you feel responsible. Many piranpa (non-Aboriginals) have died climbing Uluru…from the heat, lightening, falling…and we feel responsible. It is better for everyone to stay at the bottom. And Bob’s my uncle.”

Sure enough, for dinner this night I hook up with Damien’s uncle, Bob Taylor, a descendant of the Arrernte people who has been conducting under-the-stars private bbqs for years, what he calls the Mbantua Dinner tour (Mbantua is the original Aboriginal name for Alice Springs.) Bob was a professional cook for 26 years, including a stint in Europe, but now he’s built up an immunity to indoor kitchens.

He first takes me to Simpsons Gap in the Western McDonnell Ranges, where we hike into a sinuous slot canyon in the last healing rays of light. The medicinal smell of eucalyptus drifts through the gorge, families mill about on picnic, rock wallabies skitter, and a couple of seasoned women strum reverie harps to give a more mystic feeling to this already mystical place.

Then we drive to a camping spot and Bob sets up shop. He offers up a home-brewed cordial, lemon with river mint, along with roasted macadamia nuts with bush tomatoes and crushed wattleseeds. He feeds mulga wood into his halved-oil drum, lights it up, and begins to cook. They say when Bob Taylor barbecues, vegetarians convert.

It’s a deliciously long and resplendent night, lingering over emu sausages, grilled kangaroo filet, and Outback beef hotpot, the stars salt spilled on a black onyx table. Over a quandong and white chocolate steamed pudding we watch a screeching night owl flit around the surrounding trees, and finally head back, as the morning will be quite early.

Up at 4 am this time, and for good reason. Am joining Outback Ballooning for a dawn flight over the Outback. On the bus to the launch site the metal music is blasting, intended to shake us awake. “Is that “Stairway to Heaven?” I ask, eyelids still half-mast.

“Are you kidding? Led Zeppelin is the one group banned on a balloon trip,” the driver rebukes.

Flapping my sides in the crisp night air of the desert I watch as the crew inflate the balloon, using flames to grow the long, flaccid silk dangle to something of size and splendor. When swollen to full, I jump into the airship along with captain and crew, and off we sail, just as the first rays of day shatter the horizon. Peering down it looks like a giant broom has swept away all the topography. For as far as I can see in three directions it is stony, dead flat and summoning, like drums just out of sight. There are no fences against possibility in sight; only an endless promise. In the other direction I can see the cardboard scenery of the MacDonnell Ranges, and some odd looking man-made domes, which I am told is a top-secret American submarine base.

Gliding along there is an ineluctable sensation of being unhinged, our bodies eggs in a flying basket. With the burner’s warmth pressing against my eyelids, the breeze is a cool, feminine hand over a throbbing forehead; the earth below curves to a vanishing point in tier upon tier of rubicund-brown.

It’s all too beautiful hovering over the Red Center of the Northern Territory. I have to do nothing, except look down and around and admire. Effortlessly the balloon carries me to unexpected places. This is the high art of not-doing, and I plan to simply hold on as the envelope just keeps on sailing, second star to the right, and straight on till dreamtime.

Richard – thanks for this post. It brings back very good memories of time I spent in and around Alice Springs last year