My plane bucks like a wild horse on the final approach before landing through disturbing clouds that crowd late afternoon summer skies over Manila. Beside me a Singaporean Flight Engineer and his wife eagerly peer out the window for a first glimpse of the city. “We’ve been visiting the islands a number of times,” she explains, reminding me of how neighbouring Asians refer to the rest of the country, “and can’t wait to get back. Philippines are among those destinations that really give you a feeling of nostalgia.”

When I reach my hotel, daylight is already fading. I stroll down Baywalk (situated Roxas Boulevard, facing Manila Bay) where many sightseers enjoying their time at the sunset. It is said that the sunsets that flame over Manila Bay are without equal in any part of the world. Watching its legendary view is the city’s most fervently observed ritual: as the sun sinks toward the horizon, the western sky is a blazing banner of scarlet, crimson, yellow, purple, and the seawaters below seem liquid gold. Floating on the air comes the sound of flash cars and taxis passing along asphalt boulevard, church bells tolling. On the shore of the bay, steamy twilight breeze is soft as I amble the promenade of Baywalk, looking for a cozy place to cool my heels. Opposite sides are cafes made of container vans, a park’s fountain, churches, and restaurants fill in with its waiters and customers.

When I reach my hotel, daylight is already fading. I stroll down Baywalk (situated Roxas Boulevard, facing Manila Bay) where many sightseers enjoying their time at the sunset. It is said that the sunsets that flame over Manila Bay are without equal in any part of the world. Watching its legendary view is the city’s most fervently observed ritual: as the sun sinks toward the horizon, the western sky is a blazing banner of scarlet, crimson, yellow, purple, and the seawaters below seem liquid gold. Floating on the air comes the sound of flash cars and taxis passing along asphalt boulevard, church bells tolling. On the shore of the bay, steamy twilight breeze is soft as I amble the promenade of Baywalk, looking for a cozy place to cool my heels. Opposite sides are cafes made of container vans, a park’s fountain, churches, and restaurants fill in with its waiters and customers.

Then, as night arrives, those rows of inviting lights that line beside the boulevard cast light upon the gay atmosphere of the coast. Locals and foreigners rendezvous at restaurant I dine in. among them an Australian photographer who has been busy capturing images of nature’s splendid display. “Darwin has also beautiful sunsets that slip into the Timor Sea,” he notes, “but Manila Bay’s are unusual”. We engage in several conversations along with the others. One Filipino tells me that aside from exceptional sunsets, the bay is also famous in history. “Just a few miles from these waters heading south,” explains Ramon Cadiz, “was the scene of desperate and blood-spattered fighting.”

Manila Bay is the finest harbour in the Far East. At its entrance, standing like an isolated guard, is the 2-square-mile fortified rocky island of Corregidor. Opposite side, to the east, is the 30-mile-long peninsula of Bataan. Here, during World War II, Filipino-American forces resisted Japanese attacks. “It was 1942. I was only 7,” recalls 73-year-old Ramon, “when father brought and hid us to Laguna. I could hear the terrifying thunderous bomb sounds coming from Japanese aircrafts.” In early 1942, the Filipino-American troops, under General Jonathan Wainright, defended Bataan against the Japanese until forced to surrender on April 9, 1942, and by May of same year, Corregidor fell to the Japanese after 4 months of fierce fighting. Out of 600,000 Filipino-American soldiers that were made to march 70 miles to prison camps, over 100,000 died of starvation and maltreatment. U.S. forces recaptured Corrigidor and Bataan in February 1945. Today, the island-fortress of Corrigidor serves as a WWII memorial. It is one of the world’s most symbolic legacies of war.

Long before the United States regimented the Philippine Islands (1898-1946), the country was under Spanish control. North-end of Roxas Boulevard (Dewey Boulevard in American colonial days) is the historic Luneta, today a large park, where many Filipino heroes died in the hands of Spain. Near the place are the ruins of Intramuros, a woeful memento of the Second World War. Once upon a time this section of present-day Manila was a medieval Spanish City. Within its walls were the massive Manila Cathedral, a number of church buildings, schools and colleges, and monasteries of various religious orders. Fort Santiago formed the oldest portion of the walls, and there were drawbridges and an ancient moat. Manila’s long past, nostalgic history made her one of Asia’s great cities; once it was the Mohammedan kingdom of a brave Filipino warriour-king Rajah Soliman; up until the Spanish conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi captured it in 1571 -who rebuilt and made Manila a Christian city. These days, one can certainly see the very old walls in Intramuros, its golf course, and several buildings that had arisen over the ashes left by war.

Long before the United States regimented the Philippine Islands (1898-1946), the country was under Spanish control. North-end of Roxas Boulevard (Dewey Boulevard in American colonial days) is the historic Luneta, today a large park, where many Filipino heroes died in the hands of Spain. Near the place are the ruins of Intramuros, a woeful memento of the Second World War. Once upon a time this section of present-day Manila was a medieval Spanish City. Within its walls were the massive Manila Cathedral, a number of church buildings, schools and colleges, and monasteries of various religious orders. Fort Santiago formed the oldest portion of the walls, and there were drawbridges and an ancient moat. Manila’s long past, nostalgic history made her one of Asia’s great cities; once it was the Mohammedan kingdom of a brave Filipino warriour-king Rajah Soliman; up until the Spanish conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legaspi captured it in 1571 -who rebuilt and made Manila a Christian city. These days, one can certainly see the very old walls in Intramuros, its golf course, and several buildings that had arisen over the ashes left by war.

The fact that the Philippines had been a Spanish colony for 377 years (1521-1898), Manila holds one of the oldest universities in the world, the University of Santo Tomas (UST). The Dominican Order founded it on April 28, 1611; it is one of the largest catholic universities in the world in terms of population whose existence is 25 years older than Harvard University. “There’s no doubt that Manila is a remarkable city in Asia” says a spokesperson for the Philippine Museum, – although Filipinos cherish no bitter memories of Western exploitation.”

Picturesque Scenes in Paradise Isles

Without its more than 7,000 islands and islets that include scenic mountains, volcanoes, caves, rivers and lakes, Philippines wouldn’t be Philippines. Known as :Pearl of the Orient Seas”, its resorts and festivals are perfect havens for international visitors.

The next morning I board a 45-minute flight to Cebu -once called “Empire City of the Visayas.” It is the oldest and first Philippine city. Since its modest beginnings in 1521 as a colony of Spain, Cebu’s historic legacy has been a magnet for travel addicts with a thirst for adventure. What make Cebu interesting are the enticing island resorts and the yearly celebration of Sinulog Festival – the grandest, most distinguished and most colourful festival in the Philippines. “Sinulog is one of those fetes that really gets in your blood,” explains Fr. Marlowe Rosales, a Franciscan priest once assigned at the city’s San Vicente Ferrer Parish. “It’s a dance ritual which remembers the Filipinos” pagan past and their recognition of Christianity.”

The next morning I board a 45-minute flight to Cebu -once called “Empire City of the Visayas.” It is the oldest and first Philippine city. Since its modest beginnings in 1521 as a colony of Spain, Cebu’s historic legacy has been a magnet for travel addicts with a thirst for adventure. What make Cebu interesting are the enticing island resorts and the yearly celebration of Sinulog Festival – the grandest, most distinguished and most colourful festival in the Philippines. “Sinulog is one of those fetes that really gets in your blood,” explains Fr. Marlowe Rosales, a Franciscan priest once assigned at the city’s San Vicente Ferrer Parish. “It’s a dance ritual which remembers the Filipinos” pagan past and their recognition of Christianity.”

Historians recited that before the first Spaniards came to Cebu, the natives of the island already danced the Sinulog in respect to their “anitos”. Then on April 7, 1521, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan arrived and planted the cross on the shores of Cebu – claiming the territory in the name of the King of Spain. With the purpose of aggrandising economic wealth and of spreading Catholicism, financed by Charles I, Magellan then offered the image of Santo Nino to Hara Amihan (Queen of Cebu) who was later named Queen Juana in honour of Charles I’s mother. Along with rulers of the island, some 800 natives were also converted to the Christian faith. However, it took 44 years before Spain made some measure of success in colonising Cebu and finally the entire Philippine Islands. After Magellan met his death on April 27, 1521 in a skirmish with natives (on the shores of Mactan ruled by Rajah Lapu-Lapu), the voyage of Miguel Lopez de Legaspi followed. And set foot in Cebu on April 28, 1565. Historians later said that during the 44 years between the coming of Magellan and Legaspi, Cebuano natives continued to dance the Sinulog (no longer for their anitos, but for the Santo Nino).

Historians recited that before the first Spaniards came to Cebu, the natives of the island already danced the Sinulog in respect to their “anitos”. Then on April 7, 1521, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan arrived and planted the cross on the shores of Cebu – claiming the territory in the name of the King of Spain. With the purpose of aggrandising economic wealth and of spreading Catholicism, financed by Charles I, Magellan then offered the image of Santo Nino to Hara Amihan (Queen of Cebu) who was later named Queen Juana in honour of Charles I’s mother. Along with rulers of the island, some 800 natives were also converted to the Christian faith. However, it took 44 years before Spain made some measure of success in colonising Cebu and finally the entire Philippine Islands. After Magellan met his death on April 27, 1521 in a skirmish with natives (on the shores of Mactan ruled by Rajah Lapu-Lapu), the voyage of Miguel Lopez de Legaspi followed. And set foot in Cebu on April 28, 1565. Historians later said that during the 44 years between the coming of Magellan and Legaspi, Cebuano natives continued to dance the Sinulog (no longer for their anitos, but for the Santo Nino).

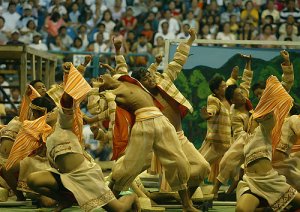

Colourful event that goes back 1521 brought into existence the foundation of Sinulog Festival, commemorating the coming of the Spanish and the presentation of Santo Nino to Queen Juana. Sinulog features the grandest ceremony: participants clothe in elegant costumes, dance to the rhythm of gongs and drums. Traditionally, the celebration takes 9 days in which major parade concludes on the third Sunday of January. Myriad pilgrims from different parts of the nation make their yearly journey to Cebu to honour the feast of the Santo Nino, whilst a surge of audience pour into the City’s Sports Complex -all wanting to witness the world class festival. Several of Cebu’s attractive spots are situated north beach resorts in Mactan Island, for example -and some in the south, as Kawasan Falls in the elevated vicinity of Badian.

Colourful event that goes back 1521 brought into existence the foundation of Sinulog Festival, commemorating the coming of the Spanish and the presentation of Santo Nino to Queen Juana. Sinulog features the grandest ceremony: participants clothe in elegant costumes, dance to the rhythm of gongs and drums. Traditionally, the celebration takes 9 days in which major parade concludes on the third Sunday of January. Myriad pilgrims from different parts of the nation make their yearly journey to Cebu to honour the feast of the Santo Nino, whilst a surge of audience pour into the City’s Sports Complex -all wanting to witness the world class festival. Several of Cebu’s attractive spots are situated north beach resorts in Mactan Island, for example -and some in the south, as Kawasan Falls in the elevated vicinity of Badian.

Nearby islands of Cebu, at its west, are Panay and Negros. Just a few hours sea travel is Panay’s Aklan Province, home of the island paradise of Boracay. With its pristine 4-kilometre white coral-sand beachfronts, friendly natives, 4- or 5-star hotels and restaurants in Caticlan, Aklan also holds the famous Filipino tradition, known the world over as the Ati-Atihan Festival. Like Sinulog of Cebu’s, Ati-Atihan too is dedicated to the feast of Santo Nino. Celebrants paint their faces with black, wear bright outlandish costumes, as they perform in revelry with the rhythmic, intoxicating drumbeats. It is the wildest among Philippine festivities that also takes place annually in January, in Kalibo, the capital town of Aklan.

Nearby islands of Cebu, at its west, are Panay and Negros. Just a few hours sea travel is Panay’s Aklan Province, home of the island paradise of Boracay. With its pristine 4-kilometre white coral-sand beachfronts, friendly natives, 4- or 5-star hotels and restaurants in Caticlan, Aklan also holds the famous Filipino tradition, known the world over as the Ati-Atihan Festival. Like Sinulog of Cebu’s, Ati-Atihan too is dedicated to the feast of Santo Nino. Celebrants paint their faces with black, wear bright outlandish costumes, as they perform in revelry with the rhythmic, intoxicating drumbeats. It is the wildest among Philippine festivities that also takes place annually in January, in Kalibo, the capital town of Aklan.

I board a sea vessel the next day to the seaport of Dumaguete City, the capital of Oriental Negros Province. Located on Negros’s eastern portion (Central Visayas Region), the bailiwick owns several pacific resorts and holds a vibrant celebration: Buglasan Festival of Festivals. Suffice to say, colourful events unreel almost every month in various places of this island. In the Provincial Tourism Office, I talk to the staff members as we scan over documents about the province’s points of interests and cultural affairs. “There are actually a number of tropical resorts in this province, “says one spokesperson, – but we suggest you go southernmost part.”

I board a sea vessel the next day to the seaport of Dumaguete City, the capital of Oriental Negros Province. Located on Negros’s eastern portion (Central Visayas Region), the bailiwick owns several pacific resorts and holds a vibrant celebration: Buglasan Festival of Festivals. Suffice to say, colourful events unreel almost every month in various places of this island. In the Provincial Tourism Office, I talk to the staff members as we scan over documents about the province’s points of interests and cultural affairs. “There are actually a number of tropical resorts in this province, “says one spokesperson, – but we suggest you go southernmost part.”

3 years back I visited several small towns in Oriental Negros, with a friend who was once a long-time resident of Dumaguete City, and had a nostalgic sightseeing excursion experience on its resorts. Among them the Sea Forest Resort in Sibulan, Forest Camp Resort in Valencia, and Santa Monica Beach Resort in Dumaguete. To see what the tourism staff has told me, I dine on Thalatta Beach Resort in Maluay-Zamboanguita, 20 kilometres south of Dumaguete City. In the resort’s restaurant that serves international and Filipino articles of food, employees explain they have just begun operating since a French-Filipino couple established the resort in February 2007. Thalatta has the centre view of Apo Island – perhaps the main attraction of the province, 7 kilometres off the southeastern tip of Negros and under the jurisdiction of Municipality of Dauin. A 30-minute boat ride from the market village of Malatapay-Zamboanguita, the small volcanic island of Apo is one of the world’s best-known community-organised marine sanctuaries, with over 650 species of fish and over 400 species of corals. “Visitors and tourists pay a fee to enter the island, “says a government worker I converse with at the restaurant, “and to snorkel or dive in the marine sanctuary there. The fees are used to maintain the spot clean and in good condition.” In 2003 Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium opened a wild reef exhibit based on the island’s surrounding reef and marine sanctuary.

3 years back I visited several small towns in Oriental Negros, with a friend who was once a long-time resident of Dumaguete City, and had a nostalgic sightseeing excursion experience on its resorts. Among them the Sea Forest Resort in Sibulan, Forest Camp Resort in Valencia, and Santa Monica Beach Resort in Dumaguete. To see what the tourism staff has told me, I dine on Thalatta Beach Resort in Maluay-Zamboanguita, 20 kilometres south of Dumaguete City. In the resort’s restaurant that serves international and Filipino articles of food, employees explain they have just begun operating since a French-Filipino couple established the resort in February 2007. Thalatta has the centre view of Apo Island – perhaps the main attraction of the province, 7 kilometres off the southeastern tip of Negros and under the jurisdiction of Municipality of Dauin. A 30-minute boat ride from the market village of Malatapay-Zamboanguita, the small volcanic island of Apo is one of the world’s best-known community-organised marine sanctuaries, with over 650 species of fish and over 400 species of corals. “Visitors and tourists pay a fee to enter the island, “says a government worker I converse with at the restaurant, “and to snorkel or dive in the marine sanctuary there. The fees are used to maintain the spot clean and in good condition.” In 2003 Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium opened a wild reef exhibit based on the island’s surrounding reef and marine sanctuary.

Moreover, the celebration of Buglasan “Festival of Festivals” brings together the finest street-dancing contingents of Oriental Negros’s 20 established festivals. With the coordination of the local government of Dumaguete City, the Provincial Toursim and other tourism stakeholders – under the leadership of Governor Emilio Macias II – turned Buglasan Festival as the culminating activity for all the festivals in the province. “Buglasan merges them altogether,” says a spokesperson for the Tourism “for days competition.” Recent gala affair started on December 21st and ended on the 31st, held at the newly constructed Sidlakang Negros Village – along E.J. Blanco Drive, Piapi, Dumaguete City.

Moreover, the celebration of Buglasan “Festival of Festivals” brings together the finest street-dancing contingents of Oriental Negros’s 20 established festivals. With the coordination of the local government of Dumaguete City, the Provincial Toursim and other tourism stakeholders – under the leadership of Governor Emilio Macias II – turned Buglasan Festival as the culminating activity for all the festivals in the province. “Buglasan merges them altogether,” says a spokesperson for the Tourism “for days competition.” Recent gala affair started on December 21st and ended on the 31st, held at the newly constructed Sidlakang Negros Village – along E.J. Blanco Drive, Piapi, Dumaguete City.

The Southern Philippines

By the time I reach Cagayan de Oro, the quietness of 2:00 a.m. dawn still lingers on the city’s entire seaport. I remain in my ship until daylight comes, then proceed to the bus terminal en route to Balingoan, Misamis Oriental, which has the nearest jump-off point to Benoni’s quay in Mahinog in the alluring Province of Camiguin.

Camiguin is one of Mindanao’s jewels and has long been a destination for rugged individualists. It is a pear-shaped volcanic island lying in the Bohol Sea – some 54 kilometres southeast of Chocolate Hills and 10 kilometres north of Misamis Oriental – hosting seven volcanoes. Five towns of the island are Mambajao (capital), Catarman, Sagay, Guinsiliban and Mahinog; the island measures approximately 29,000 hectares with circumferential road of 64 kilometres. Old Spanish documents, made available to me by its tourism, indicate that the great explorers Magellan and Legaspi landed in Camiguin in 1521 and 1565, respectively. But it was not until 1598 when the Spanish settlement was established in what later came to be the Guinsiliban town. It was only in 1679 when the Spanish took major settlement in Catarman. In 1871 Mt. Vulcan Daan erupted and submerged its old capital, Bonbon, suffocating over 2000 inhabitants, until Mt. Hibok-Hibok’s raging outburst in 1951. Since then, the residents of the island regained to live their lives normally.

Camiguin is one of Mindanao’s jewels and has long been a destination for rugged individualists. It is a pear-shaped volcanic island lying in the Bohol Sea – some 54 kilometres southeast of Chocolate Hills and 10 kilometres north of Misamis Oriental – hosting seven volcanoes. Five towns of the island are Mambajao (capital), Catarman, Sagay, Guinsiliban and Mahinog; the island measures approximately 29,000 hectares with circumferential road of 64 kilometres. Old Spanish documents, made available to me by its tourism, indicate that the great explorers Magellan and Legaspi landed in Camiguin in 1521 and 1565, respectively. But it was not until 1598 when the Spanish settlement was established in what later came to be the Guinsiliban town. It was only in 1679 when the Spanish took major settlement in Catarman. In 1871 Mt. Vulcan Daan erupted and submerged its old capital, Bonbon, suffocating over 2000 inhabitants, until Mt. Hibok-Hibok’s raging outburst in 1951. Since then, the residents of the island regained to live their lives normally.

“For tourists, Camiguin is the perfect place in Mindanao, “one spokesperson for the Island’s Tourism tells me with a twinkle in his eye, – with our “hot and cold” springs. But the main come-on to tourists is the Lanzones Festival.”

To reinvigourate myself from the weary travel, I spend the whole night at Mambajao’s Ardent Hot Spring, along with American visitors Nancy and John. Ideal for night swimming, the spot’s natural pool is about 39’C springing from depths of Mt. Hibok-Hibok – the only active volcano in the island – with picnic huts, cookout facilities and restrooms. Other springs in Camiguin include Catarman’s Sto. Nino Cold Spring, with its 2-metre deep cold spring water sprouting from sandy bottom; the cool splash of crystal blue water of Mahinog’s Macao Cold Spring; and Tangub Hot Spring, a volcanic spring by the sea – temperature varies as the tide changes. More tourist attractions are the Katibawasan Falls, White Island, Tuasan Falls, Jicduf and Burias Shoals, the Old Volcano, and a number of private beach resorts.

To reinvigourate myself from the weary travel, I spend the whole night at Mambajao’s Ardent Hot Spring, along with American visitors Nancy and John. Ideal for night swimming, the spot’s natural pool is about 39’C springing from depths of Mt. Hibok-Hibok – the only active volcano in the island – with picnic huts, cookout facilities and restrooms. Other springs in Camiguin include Catarman’s Sto. Nino Cold Spring, with its 2-metre deep cold spring water sprouting from sandy bottom; the cool splash of crystal blue water of Mahinog’s Macao Cold Spring; and Tangub Hot Spring, a volcanic spring by the sea – temperature varies as the tide changes. More tourist attractions are the Katibawasan Falls, White Island, Tuasan Falls, Jicduf and Burias Shoals, the Old Volcano, and a number of private beach resorts.

Several months ago I joined a considerable number of spectators to cheer on the four-day grand cavalcade of the island’s “celebration of bountiful harvest.” Lanzones Festival, normally held every third week of October, highlights a tableau of Camiguin’s local culture with grand parade of Lazones (a sweet-taste fruit found abundantly in the entire province). Houses, carriages, street-poles – and even people – are decorated with Lanzones and its leaves, as a thanksgiving celebration for the abundant harvest of lanzones and other agricultural products in the island. It is Camiguin’s contribution to Mindanao as a cultural destination.

Before going back to Manila, I spend the last jaunt in the northwestern portion of Mindanao (Misamis Occidental), and drop in on Aquamarine Park. Located in Libertad Bajo-Sinacaban, Aquamarine Park is a tropical resort and a prominent habitat for various marine mammals in Mindanao. It also features a wildlife park that quarters a wide display of animals – most are native to the Philippines. But the main attraction is the offshore Dolphin Island.

Before going back to Manila, I spend the last jaunt in the northwestern portion of Mindanao (Misamis Occidental), and drop in on Aquamarine Park. Located in Libertad Bajo-Sinacaban, Aquamarine Park is a tropical resort and a prominent habitat for various marine mammals in Mindanao. It also features a wildlife park that quarters a wide display of animals – most are native to the Philippines. But the main attraction is the offshore Dolphin Island.

The spot has mangroves left untouched. Out of this natural setting, cottages and hut-style suite accommodations line the mangroves where visitors can stay. About a hundred steps from the cottages is the mainland-floating restaurant, the other is on the Dolphin Island, which can be reached by a 10-minute boat ride. Dolphin Island has a big, wide pen in the middle of the ocean where it houses numerous dolphins. Although not trained, the dolphins at times would show their acrobatic skills to visitors. In my conversation with Manolito Yap, Aquamarine Park’s Officer In-Charge, he tells me that other than the site’s business aspect, Aquamarine Park is also engaged in coastal resource management. “This 60-hectare Aquamarine Park aims to balance environmental protection and tourism,” he says. “We are now on the way to put up new concrete establishments to provide more facilities and amenities to tourists.” Aside from dolphin watching, the park also offers scuba diving, snorkeling, kayaking or ride a glass-bottom boat to view the corals and fishes underneath.

Perhaps none of such places in Southeast Asia bears comparison to the alluring isles of the Philippines. Certainly hundreds of colorful festivals and captivating resorts abound the entire archipelago. No matter what blows have brought it to its knees, from western exploitation to Japanese occupation, from volcanic eruptions to tropical typhoons, Philippines has risen from ruins time and again: it’s 7,107 jewel isles remain positively resplendent – but they are only half the story. Many from the West have also found their home in the Philippines because of its distinctive culture and climate – and a country of conviviality that possesses a warm hospitality.

Perhaps none of such places in Southeast Asia bears comparison to the alluring isles of the Philippines. Certainly hundreds of colorful festivals and captivating resorts abound the entire archipelago. No matter what blows have brought it to its knees, from western exploitation to Japanese occupation, from volcanic eruptions to tropical typhoons, Philippines has risen from ruins time and again: it’s 7,107 jewel isles remain positively resplendent – but they are only half the story. Many from the West have also found their home in the Philippines because of its distinctive culture and climate – and a country of conviviality that possesses a warm hospitality.

Junfil Olarte is a Professional Aeronautical Engineering Technician and a Freelance Writer recently employed at Singapore Aviation Services Co. Pte Ltd. To contact Junfil, email to Junfil

Leave a Reply