It’s a short ferry ride to Île de Gorée (Gorée Island) from Senegal’s capital, Dakar. I wonder if I can take another day of slave museums in my worn-out state after a severely delayed flight. I quickly regret this stupid thought. Of course I can; it’s only a lack of sleep. It bears absolutely no comparison with what these people went through, so I’m sure that I can find the energy to pay my respects.

Everything is calm belying the awful history that once played out here.

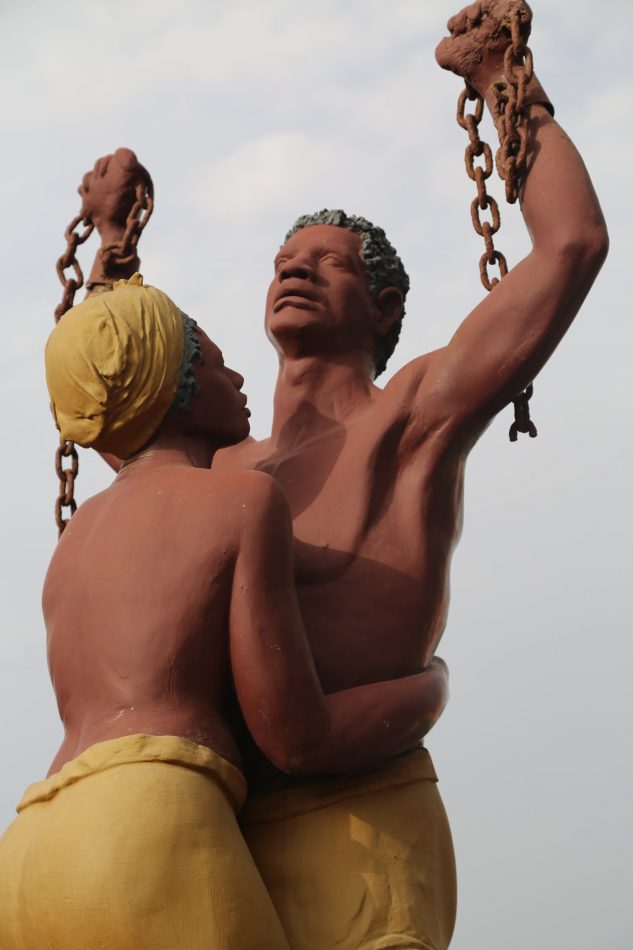

The bay is actually rather quaint. The ferry skirts around to the far side of the island before landing. We are the second ferry of the day, so it’s still relativity peaceful until we disembark. I notice how the Senegalese tower over the rest of us. The men and many of the women are very tall, so very different to the shorter Ghanaians, São Toméans and Moroccans that I have become used to being with. Colourfully painted fishing boats are beached and a few picturesque cafés and restaurants await the day’s business. Everything is calm belying the awful history that once played out here. I follow Olivier and Aida (my guides) to a memorial statue. Gifted by Guadalupe, the Caribbean island, as a mark of respect for the thousands of slaves that left here for their plantations, it depicts a black man in chains being hugged by a woman.

The slave house museum.

Next door to this is the slave house museum. It’s completely different from the harsh fortifications of Cape Coast Castle, where the rigid, dominating structure gave an indication of battle, repression and struggle. This is a small, pretty house made of red clay, with a small courtyard and a sweeping winged staircase to the officers’ chambers on the upper floor. Rich Senegalese and French are currently buying similar buildings on the island as weekend retreats.

Historians remain unsure as to the extent of the role Gorée Island played in the slave trade.

A tour presentation is being given in French, so Olivier, Aida and I stand in a side room whilst Olivier quietly provides some information. Olivier knew Boubacar Joseph Ndiaye up to his death in 2009; he was the advocate, founder and curator of the Maison des Esclaves (Museum of Slaves). Whilst historians still remain unsure as to the extent of the role Gorée Island played in the Atlantic slave trade, Ndiaye believed that over a million slaves passed through this building. It’s a similarly awful story to the one from Cape Coast Castle in Ghana. The only change here is that the perpetrators were French, rather than English, Dutch or Portuguese. One room is designated for jeunes filles, which was a separate holding cell for virgins with full breasts as high prices would be paid by the slave companies for these girls, almost as much as for the strong men. Despite the lack of certainty regarding the island’s historical role, the great and good have all paid their respects here. On his visit here, Nelson Mandela spent time in a small solitary confinement chamber. Inside it’s too small to be able to stand full height, yet the chamber is also not wide or long enough for a prisoner to lie straight. There is a small Door of No Return here also. This exit point would lead directly to the jetty where large slave boats were docked in the deep waters of the harbour.

The baobab tree.

A tall, thin man with no teeth chats to Olivier as we take in the charming vista of the Atlantic Ocean from the officer’s chambers. Olivier checks if I will agree to let this man do the tour of the rest of the island instead of him. The man is known as the Colonel. He has lived on the island all of his life and given tours to Bush, Obama and Mandela, but he says work is hard to come by as tourism is down. I’m happy to help out.

The Colonel leads us out of the house and along a lane of similar ex-slave houses and small churches that have now been adopted as holiday homes. At a junction a large grey tree stands tall. An elasticated rope has been tied to a signpost next to the tree. The other end is wrapped around a little girl’s waist. Her two friends skip and sing happily with her. This is totally incongruent to how the island was, yet it’s wonderful that they can do this now so freely.

The distinct baobab tree I know from the pattern on the shirt of the Senegalese football team. The Colonel explains that the trees have great longevity and the trunks are often hollow as the ancient wood in the middle disintegrates, making it difficult to tell the age of such trees. The fruit of the baobab, called monkey bread, is made into jam and juice; the leaves can also be eaten raw.

Gorée was one of the first places in Africa where the Europeans settled.

The Colonel now guides me around the rest of the island. Gorée was one of the first places in Africa where the Europeans settled. First here were the Portuguese in 1444. It then swapped hands between the Dutch and the Portuguese, until the English took it. Finally the French gained control from 1677 until Senegal’s Independence in 1960. We climb the baobab-lined lane up the hillside. Artists display their colourful wares against the stone walls. One artist creates small drawings made from different coloured sand found across the country.

La Castel.

At the top of the island, known as La Castel, is the WWII Commemorative Monument in the shape of a white sail and beyond it is a large metal cannon. The Vichy cannon is one of the biggest of its type ever made. The huge gun was placed on the island by the French during World War II. It was used only once on the 23rd September 1940 to sink an English battleship that was mistaken for a German one. The Colonel points into the bay and explains that this is why the ferry loops around the island, taking a longer route to avoid the wreckage left by the deadly weapon. He also tells me that many tunnels were dug under the island (like those in Gibraltar) for the purposes of war. The Colonel points out the now damaged tips on the gun barrels that prevent any further firing.

As if the island didn’t already have enough atrocities associated with it without this. Yet now all around La Castel local artists display their wares, some traders sitting calmly drumming in the shade, other quietly producing more goods. Creating in a place of destruction is truly commendable. Perhaps it’s the only way we can move forward.

Centre ville.

Back in the small centre ville, despite the tourists, the young men of the island begin their Sunday football match on the small sand pitch next to the post office. I stand and watch for a while as Olivier introduces Aida to more of his friends.

It’s warm, a pleasant thirty-one degrees, with a cooling ocean breeze. It’s a wonderfully charming place. Despite its history, it’s now enchanting, full of quaint lanes, colourful buildings and happy residents. It’s been a tough few days from Cape Coast to this, yet I’m enjoying myself in a place where I thought I wouldn’t.

On the way to lunch Aida meets her brother. It was not planned at all as both live in different parts of the city. Whilst they have the same mother and father they have never lived together. The brother had to move to make room for his younger sibling as the family house was full when Aida was born and so he had to live with his grandmother. Over lunch, poulet yassa (chicken and rice) shared between us, I ask about family life. Aida says she has no idea how many live in her house, she says that cousins and other relatives come and go. It is a large house, left by her father, now dead, but ran by her mother and grandmother even though her eldest brother is the de-facto head of the family. This seems to be the norm. Olivier is unusual in that he has a small family as he was working abroad for so long. He has only one son, living with his son’s mother, but a few nephews of his wife often stay with him.

A Little Piece of Paradise.

We take the ferry back to Dakar. Many locals have small hand rattles which give a constant backbeat to our journey. Everybody touches my white skin, especially the children. It never feels threatening, just like little pecks on my arms or legs.

Back on the mainland, one of this morning’s sellers that I chatted to earlier greets me. I smile and show him my new Senegalese football shirt bought on the island. “Hey Olivier, he’s Senegalese now.” We all laugh together. These are the warmest people I think I’ve come across. How can I possibly say I have enjoyed this morning considering where I have been, but I really have. Gorée Island is a little piece of paradise; clean with cool fresh air – it has the smell of the ocean – with its neat and tidy buildings, amazing art, wonderful people and just one or two crazies. Positivity has definitely won out over negativity here.

nice article

I was here last year

Abdul – thanks.

Dave – hope it summed up your feelings too? (Thanks for the additional photos).