Four hours after leaving Accra, through insane traffic jams, I reach Cape Coast. I am not sure this was the right thing to do today but I am here now. On the concrete expanse of the town square black and red canvas tents have been erected. The locals are dressed in their traditional clothes for a funeral day. Around the corner from this is Cape Coast Castle. With a warning from my driver to avoid the hawkers, I pay my entrance fee and join a tour group. I’m the only white in a group of twenty-five.

Outside the male slave room, the guide begins his tour. Although originally built by the Swedes, the castle was conquered by the British from the Dutch in 1664 and became the headquarters of the British administration of the Gold Coast. Less than twenty kilometres away is Elmina, the Portuguese castle and Dutch slave centre, but sadly these are only two and the most renowned of the many slave forts that still exist along the coastline. Originally these were strongholds for the trading of gold and ivory before they became the awful dark dungeons where masses of slaves would wait in inhumane conditions before being shipped across the Atlantic. Appropriately there are a few drops of rain as we listen. It doesn’t seem right that the sun would shine here. I look around my group. There are three nuns in plain habits and two in colourful dresses with “Sacred Heart Catholic Church” badges. The guide points to the steep slope down into the shadowy chamber. Above us, built on top of the male slave room, is a church. This was the first Anglican church in Ghana.

We are taken into all five chambers of the male slave room. The chambers are dark. Now there are some spotlights to be able to see the way. During slave times there would have only been a couple of holes in the wall that would allow the sunlight in. Around two hundred men, chained together, would be held in each chamber. The first chamber was called the Strong Chamber. Slaves were measured for size and strength, the bigger the specimen, the better the price.

The slaves – actually human men – would breathe, sleep, eat, sit, lie, shit and piss chained up in the dark. There are just two small drainage channels gouged in the ground for waste to flow out. In the last chamber slightly more light was permitted. This was needed so that the slaves – human men – could be branded and then forced down the passageway to the tunnel and out to the ships. These rooms would be the last thing they would see before being transported to unknown destinations in the New World, to the Americas and the Caribbean. Many, somewhere between ten and fifteen percent, would perish at sea. The opening to the tunnel is now blocked off and a shrine has been placed there, beneath which wreathes have been left on the floor.

The slaves – actually human men – would breathe, sleep, eat, sit, lie, shit and piss chained up in the dark. There are just two small drainage channels gouged in the ground for waste to flow out. In the last chamber slightly more light was permitted. This was needed so that the slaves – human men – could be branded and then forced down the passageway to the tunnel and out to the ships. These rooms would be the last thing they would see before being transported to unknown destinations in the New World, to the Americas and the Caribbean. Many, somewhere between ten and fifteen percent, would perish at sea. The opening to the tunnel is now blocked off and a shrine has been placed there, beneath which wreathes have been left on the floor.

My eyes adjust gradually to the daylight back out on the courtyard. My brain cannot make sense of the sweeping white fortress in front of me, the stateliness of the building and the allure of the blue ocean it towers over. Black cannons sit proudly on the white castle walls. Beyond them the sandy beach is full of colourful fishing boats. Underneath my feet are the dungeons, plus two vast water wells and four graves.

The first one belongs to the first black Anglican pastor of the castle, Phillip Quarcoo, who died here aged seventy-five. Next to this is the grave of C. B. Whitehead, a thirty-eight year old British soldier who was killed by the Dutch. George MacLean’s grave is next. MacLean, who died at forty-six, was the British Governor of Cape Coast between the years 1830 and 1844. The tour guide explains that MacLean was respected for his sense of justice toward African customs and also for upholding British commitments, so much so that trade volumes increased dramatically under his command and yet, ironically, it was known that MacLean had a black mistress. His wife, Letita Elizabeth Landon, is buried next to him. She died at thirty-six, two months after arriving in Cape Coast. One theory is that she died of malaria, but other tales abound that she may have poisoned herself when she found out about MacLean’s black mistress and another suggests that the mistress may have poisoned her to keep MacLean all to herself. However, it is clear that the black pastor lived considerately longer than the three whites.

The first one belongs to the first black Anglican pastor of the castle, Phillip Quarcoo, who died here aged seventy-five. Next to this is the grave of C. B. Whitehead, a thirty-eight year old British soldier who was killed by the Dutch. George MacLean’s grave is next. MacLean, who died at forty-six, was the British Governor of Cape Coast between the years 1830 and 1844. The tour guide explains that MacLean was respected for his sense of justice toward African customs and also for upholding British commitments, so much so that trade volumes increased dramatically under his command and yet, ironically, it was known that MacLean had a black mistress. His wife, Letita Elizabeth Landon, is buried next to him. She died at thirty-six, two months after arriving in Cape Coast. One theory is that she died of malaria, but other tales abound that she may have poisoned herself when she found out about MacLean’s black mistress and another suggests that the mistress may have poisoned her to keep MacLean all to herself. However, it is clear that the black pastor lived considerately longer than the three whites.

Under the castle walls are the women’s cells. There were two separate cells where up to five hundred women were imprisoned. Often raped by the white guards, their babies would be taken to local schools and then subsequently sent to the plantations as supervisors due to their lighter skin. Those women who were strong after pregnancy returned to the slave rooms. The weaker ones were either shunned or more usually killed.

I notice outside one of the chambers, a sign on the wall says, “Akwaaba.” This means ‘welcome’ in Twi (the local language). I can’t make much sense of anything here and I definitely don’t understand this.

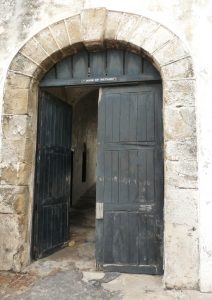

Next to these cells, at the end of the sloping passageway, is the Door of No Return.

We file through it slowly and out of the castle. The guide quietly explains that the slaves would have been chained together at the ankles and squeezed into small ships and then, out in the bay, transferred to larger vessels, which had names like “Liberty” or “Jewel of Africa”. He adds that nobody knows how many left this way and that the estimates vary widely. Over a period of more than three hundred and fifty years of slavery, it is thought that at least ten million slaves left the African continent.

We file through it slowly and out of the castle. The guide quietly explains that the slaves would have been chained together at the ankles and squeezed into small ships and then, out in the bay, transferred to larger vessels, which had names like “Liberty” or “Jewel of Africa”. He adds that nobody knows how many left this way and that the estimates vary widely. Over a period of more than three hundred and fifty years of slavery, it is thought that at least ten million slaves left the African continent.

Now full of local fishermen and other traders, the beach behind us was then for white men only. As we listen to the narrative, a scrawny kid begs me for money and a few women try to sell their food. The boy then hassles one of the nuns. The guide interrupts his presentation to move him away and advises the nun to protect her bag.

We go back inside. From this side, the door is labelled the Door of Return.

Now the “Akwaaba” sign makes sense. Welcome back; to forgive but never forget, to rise above. I recall my experience at Robben Island and Nelson Mandala’s wonderful words. I’m nearly in tears, my mind totally blown; so how must a black person feel being here. As I come to terms with this, the guide graciously beckons me through before him. Thank you kindly, but as the only white man in this group, I will wait until everyone has gone through before me.

Now the “Akwaaba” sign makes sense. Welcome back; to forgive but never forget, to rise above. I recall my experience at Robben Island and Nelson Mandala’s wonderful words. I’m nearly in tears, my mind totally blown; so how must a black person feel being here. As I come to terms with this, the guide graciously beckons me through before him. Thank you kindly, but as the only white man in this group, I will wait until everyone has gone through before me.

We are shown the cells where unruly prisoners would be kept. It’s an old storeroom with no natural light. The three locked doors would only be opened once all the prisoners were dead. It’s absolutely shocking. I am numb, constantly shaking my head at what I see and hear.

The group now follows the guide upstairs. I was not prepared for the luxury of the large room where McLean would hold court and, beyond it, his grand bedroom and chambers. Fourteen large windows allow the light and sea breeze to flood in. It’s a total contrast to the dark, hot slave chambers beneath us. How could anyone sleep peacefully here?

On the way out, I pass a plaque on the wall.

In everlasting memory

Of the anguish of our ancestors.

May those who died rest in peace.

May those who return find their roots.

May humanity never again perpetuate

Such injustice against humanity

We, the living, vow to uphold this.

Pete this is one of those things I could never wrap my head around. I just cannot come close to understanding how I could treat another living thing in this fashion; when you are talking human beings, my disbelief rises so many levels. It is just….unreal. Thanks for providing a glimpse into this world.

Besides the ones I visited in Ghana – I also saw similar ones in Senegal – hard to walk through these tiny rooms 🙁

I agree with you both. Part 2 will cover Senegal in a few weeks. Seems crazy to say but these sites, like Auschwitz, have to be seen. Puts things into perspective.

when do they build the three castles