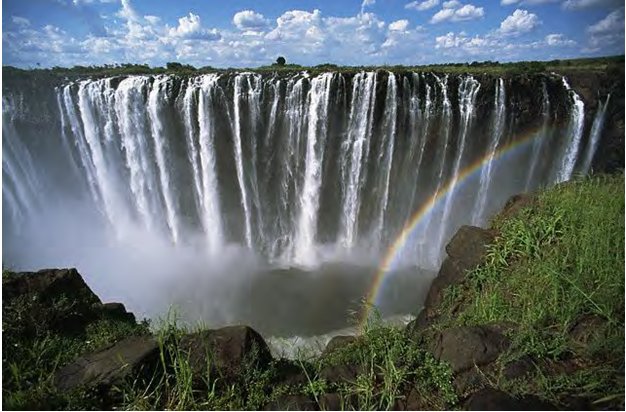

It was Valentine’s Day when I first saw the river; it was love at first sight. Along with a party of tour operators, I had been shuttled between game parks and hotel lobbies for days, all leading up to this: Victoria Falls. While the other occupants of the Land Rover pressed for a glimpse of the great falls upstream, I looked the other way, out of habit. Some 350 feet below the bridge we were driving over, a mighty river coiled and cursed through a dark basalt gorge. I could see two rapids interrupting the otherwise peaceful stretch, between the hairpin curves that divide the Third Canyon from its cousins. They were pieces of effervescence, feather-white, inviting. They looked as though they could be run.

It was Valentine’s Day when I first saw the river; it was love at first sight. Along with a party of tour operators, I had been shuttled between game parks and hotel lobbies for days, all leading up to this: Victoria Falls. While the other occupants of the Land Rover pressed for a glimpse of the great falls upstream, I looked the other way, out of habit. Some 350 feet below the bridge we were driving over, a mighty river coiled and cursed through a dark basalt gorge. I could see two rapids interrupting the otherwise peaceful stretch, between the hairpin curves that divide the Third Canyon from its cousins. They were pieces of effervescence, feather-white, inviting. They looked as though they could be run.

In 1855 David Livingstone was traveling down the upper Zambezi by canoe, hoping to find the African equivalent of the “Northwest Passage,” a water route into the heart of the continent that would allow colonization, the end of Arab slave trading, and Christian conversion of heathens.

But when he came to the huge falls he named for his queen, Victoria, and peered over the edge, he abandoned his quest, and made his way overland to the coast. The Zambezi below the falls remained unnavigated ever since. I thought I could correct that.

A few months later I flew to Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, to meet with the Minister of Tourism to request a permit to make the first descent of the Zambezi. It was going to be a tough sell, as nobody had done anything like this since Livingstone, and it seemed to most a risky endeavor. I flew to London from Los Angeles, and caught the first flight south, spending almost 20 sleepless hours in the transit. When I landed I made my way directly to the Ministry of Tourism, stepped up the steep flight of stairs, and made my way to the Minister’s office. He invited me in, and I sat on the far side of his big desk and explained why I thought running the Zambezi would be a great thing for Zambia’s pallid tourism industry. He listened respectfully, and then got a summons from his assistant, and excused himself from the room. I suddenly felt a wave of wooziness wash over me, extreme jetlag, and I slumped over onto the Minister’s desk, and promptly fell asleep. The next thing I knew he was shaking me awake, saying my snoring could be heard through the building. I blew it, I knew. My dream of pioneering the Zambezi dashed against the rocks. The Minister sat in his high-backed chair and said, “I’ve decided to grant you the permit to run the Zambezi. I’ll have the papers drawn up this afternoon.”

On October 26th my expedition team collected in Livingstone, Zambia: Eight of Sobek’s most experienced guides, along with actor LeVar Burton, an ABC film crew, and two sappers from Zimbabwe who would sweep the beaches for landmines before we camped.

I squeezed hands with a group of local boys who had scrambled down the steep slope to see us off. Slipping on a pair of studded cotton gloves, I settled in the seat of a five-meter-long inflatable raft. My passengers: photographer Michael Nichols and Joanne Taylor, both somber as the dark canyon walls. Setting the bowline free, I let the boat drift upstream in the eddy to its confrontation with the rapid known as The Boiling Pot.

Then I dug the oar blades deep, powering out of the eddy and into the main current. The first stroke seemed solid, and I was confidently preparing for the next when the boat canted up a wave. The right oar sliced ineffectually through the air. I grappled with the ill-spent oar and saw, through the heaving water, a black wall looming. With a panicked push on the other oar, I turned the bow toward the wall, which was hurling water from its face.

Three meters from the wall I dropped the oars and held on. A blast of water pushed the boat up on its side, where it hung for a tense second. Through the wash of white I saw Michael, camera pressed against his eye, still shooting; then I thought I heard Joanne scream. The boat plunged over, upside down, into the rolling mess.

Photo compliments of MTSobek.

I had capsized in the first rapid of the Zambezi, minutes after launching our expedition. The president of Zambia watched from the bridge above, turned to a reporter and asked, “Is that how they do it?”

But we continued, with portages, more capsizes, and mishaps. About half way down the river one of the rafts was attacked. A ridged snout lunged from beneath and, sinking two long rows of teeth into the raft, exploded one of the inflated tubes. The oarsman, John Yost, reacted instinctively and defensively: he lifted an oar out of its oarlock and began slapping the croc over the head with the blade. The croc made a second lunge, then dived and disappeared. Yost frantically rowed the half-deflated raft to shore, and the other boats, including a kayak paddled by LeVar Burton, made a hasty landing on the nearest beach. LeVar Burton called in the helicopter, and flew away, not to be seen again.

The rest of us continued cautiously downstream. A few days later, late in the afternoon, we came to another spectacular rapid that split the river, one uncharted and unnamed. We scouted, and decided it looked runnable straight down the middle. One of the guides, Neusom Holmes, volunteered to row first. He rode cleanly over the first wave, then rode sideways up the second and flipped.

He and his passengers disappeared in the dusk downstream, swimming for shore. Then Jim Slade capsized in the same place. Two flips in one rapid. Now it was my turn.

I desperately surveyed the rapid for a “cheat” run, but I couldn’t even see 100 meters ahead in the fading light. I had no idea how the others, who had capsized, had fared, whether the water, the rocks, or the crocs, had done any damage. I quickly tightened all the ropes that held the gear in my boat, and took out my waterproof diary and camera box. Then I stepped from the boat, kicked it out into the current, and watched.

I desperately surveyed the rapid for a “cheat” run, but I couldn’t even see 100 meters ahead in the fading light. I had no idea how the others, who had capsized, had fared, whether the water, the rocks, or the crocs, had done any damage. I quickly tightened all the ropes that held the gear in my boat, and took out my waterproof diary and camera box. Then I stepped from the boat, kicked it out into the current, and watched.

The abandoned boat descended into the maelstrom farther to the left than the rafts before me, pirouetted in the first wave, and then rode up over the plume of the second wave, right-side-up. I stumbled down the side of the rapid, and found my boat pitching in an eddy, still upright, with Neusom and Slade inside bailing.

Finally, in the early afternoon of November 5, the current of the Zambezi died in the waters of Lake Kariba. The first descent was over.

I wished I could send a report to Livingstone so he might have the final chapter on this river he spent so long exploring, so he might close the book.

The Zambezi curls through the final gate into this artificial lake, Kariba, sparkling like hammered gold. And like some sort of bottomless adventure treasure, tens of thousands have followed in our oar strokes and rafted the Zambezi, and it is now the top tourism draw in Zambia.

High Adventure today on the Zambezi:

Wow! What an adventure….a croc?! That would have been the end of it for me. Great story!