I am a native Bostonian, retired from a career as a consultant to small businesses. In 1993, when my brother and his friend came up with the concept of a Museum of Bad Art, I offered to take on the role of Director of Financial Enablement.

Around 2000, the other founders moved on to new ventures. I assumed the role of Executive Director.

We have strived to keep MOBA admission free since day one. The only way to do this is to find free exhibit space, pay no salaries, and depend on volunteer support.

Nowadays, Curator in Chief Michael Frank and I oversee the day-to-day operation. When we need help setting up exhibits, organizing archives, or updating our website, we take to Facebook to recruit volunteers for help.

Our volunteers are a mix of long-term and one-off helpers. Most tasks are on-site work, but we are starting to look for remote support, like the webmaster who supported MOBA from Quebec, Canada for at least 5 years.

Many of the MOBA volunteers feel like old friends. They have been fans of MOBA for years and are regulars at our gallery.

Q. MOBA started in a basement in Boston. Could you walk us through its evolution from humble beginnings to becoming the most unique museum today?

MOBA came into existence serendipitously when a friend stumbled upon an abandoned painting in a trash pile. Scott Wilson, an art and antique dealer, was driving down the street one day when he spotted a painting leaning forlornly against a trash barrel.

The painting did not pique his interest, but the gilt frame did. He stuck it in his truck, planning to discard the painting, clean up the frame, and sell it.

The painting would have met a different end had Scott not stopped by my brother’s (Jerry Reilly) house.

When Jerry saw the painting, he declared, “It’s so bad, it’s good.”

Jerry and his wife, Marie Jackson, decided to hang the painting over their fireplace and name it “Lucy in the Field with Flowers.” The painting went on to become the cornerstone of the Museum of Bad Art.

This salvaged treasure inspired Scott and his friends to look for other “bad” paintings in trash piles, thrift stores, and white elephant sales. The collection of paintings steadily expanded over the years.

When Jerry and Marie moved into their new house, they threw a housewarming party with a theme of “Opening of the Museum of Bad Art.” The party was a one-night event, with about 50 people in attendance. I was there to help him plan the party.

The basement walls were painted white, and track lighting was installed. Each piece of art was hung with a typical museum information card.

Despite the negative connotation of the theme, there were no negative comments about the art or the artists. We explained our interpretations of these paintings.

The party guests were enthralled by the art. They called their friends to come and see the paintings, and by midnight, there were over 100 people in the small house.

The next morning, five of us decided that we needed to keep the ball rolling. We sent weekly email bulletins (remember this was 1993) to the party attendees and everyone else we knew.

Word-of-mouth led to local newspaper coverage and visitor traffic to Jerry and Marie’s house grew.

We realized we needed a larger space. A friend who owned a vintage movie theater allowed us to use the basement. Dedham Community Theater housed the MOBA gallery until 2000.

Meanwhile, we opened another gallery in the basement of an old movie theater, the Somerville Theater. Over the years, we held special exhibits in the lobby of an animal hospital, a cable TV studio, and a pop-up store in an apartment building.

The Somerville Theater was our main location for almost 20 years. But late 2019, we had to vacate that space.

Like everyone else, we realized that we needed to shift from in-person experiences to virtual ones. We started developing virtual programs and presenting them to public libraries, community groups, corporate events, and schools across the United States and Canada.

In the summer of 2022, we resumed our efforts to find gallery space. Dorchester Brewing Company in Boston had just opened a new event room in the brewery, and they were seeking unique ways to make the space memorable.

After our first successful meeting with Dorchester Brewing Company, we were confident that we had found a new home for MOBA.

The MOBA gallery spills out all over the brewery, showcasing a rotating collection of 50 to 60 art works.

From the start, we were drawn to these pieces. We saw them as “art too bad to be ignored.” MOBA art has the same effect as any worthwhile art: it makes you think and wonder what the artist was trying to convey. It prompts conversations and even arguments. It provides you a glimpse into the heart and soul of the artist.

At one point, we started to question if our reaction to bad art was interesting only to us. But then someone offered us a helpful insight that helped us see things in a new light: When a group of people walks by an art gallery and someone exclaims, “Wow!”, you don’t know if they’re reacting to something good or bad until you turn around.

Either way, there is an instinct to share the work.

We decided our mission was collect, exhibit, and celebrate art that would be seen nowhere else.

Q. Obviously, not all bad arts make the cut. How do you define bad art, and what criteria do you use to select your collection?

Curator-in-Chief Michael Frank prefers we call it MOBA-worthy art.

First and foremost, it must be truly art. To Michael, that means it is a sincere effort to make an artistic statement. But something has gone wrong in the concept or the execution. Poor technique is not enough. The image should be compelling.

Sometimes the artist has obvious technical skills but may intentionally or inadvertently make mistakes or come to the realization that the concept is unworkable.

Some art may have unusual themes that leave viewers scratching their heads, while other pieces contain over-the-top imagery that is nonetheless remarkable, regardless of the artist’s intent.

The Curator-in-Chief has the final say on what makes MOBA-worthy art. As he puts it, “Bad art is like pornography in that, while I find it difficult to articulately define it, I know it when I see it.”

(Please do not infer that Mr Frank is an expert on pornography!)

Q. What are your three favorite bad arts from the museum’s collection?

That’s like asking someone to decide which child is their favorite! But I’ll try. Here are 3 that I like very much.

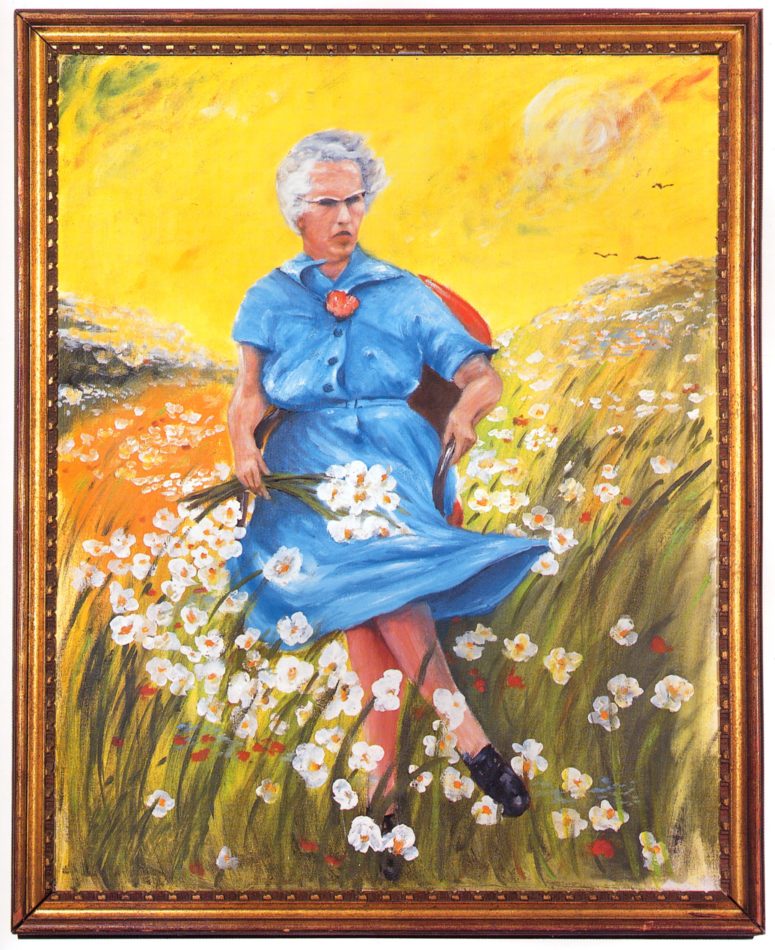

Lucy in the Field with Flowers

Unknown

30” x 24”, oil on canvas

Rescued from the trash in Boston, MA

The motion, the chair, the sway of her breast, the subtle hues of the sky, the expression on her face; every detail cries out “masterpiece.” This painting was the seed that grew into MOBA when Scott Wilson rescued it from the trash. He intended to discard the painting and sell the frame, but his friends Jerry Reilly and Marie Jackson convinced him to share his find with the public.

This is the piece that started it all.

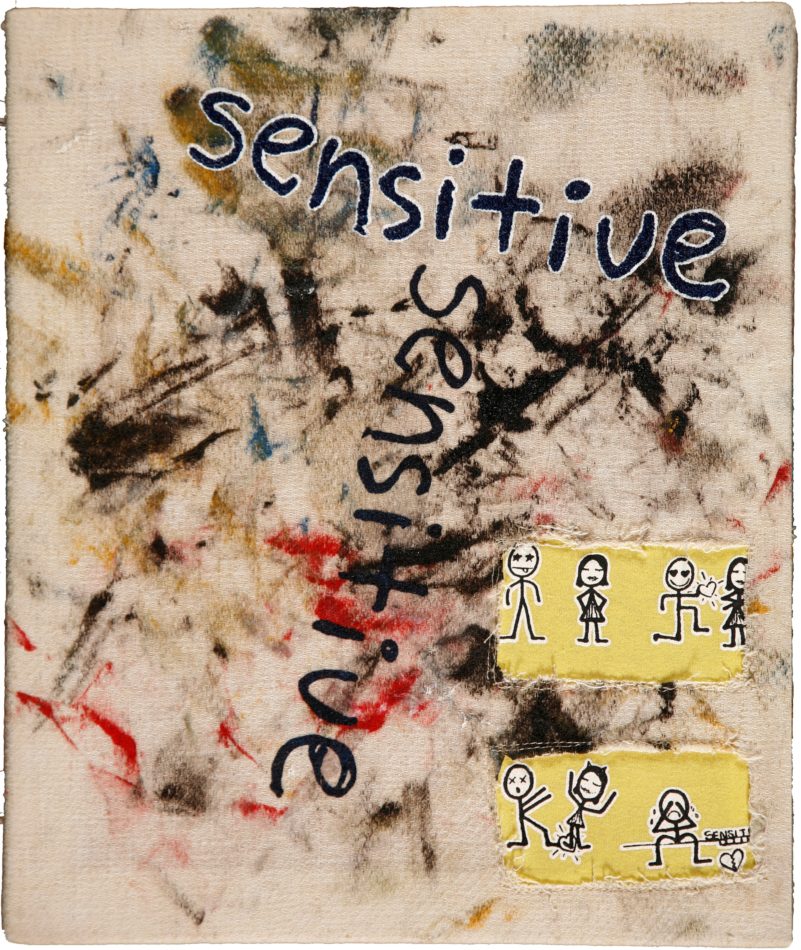

Sensitive

Anonymous

20” x 16”, marker on cloth with paper

Purchased at a Boston thrift store

There may have been an argument that ended with the artist yelling, “Sensitive? You want sensitive? I’ll show you sensitive.” The outraged splashes of dark color, the scribbled words, and even the angry stick figures are callous, thick-skinned, and indurate – no matter how insistent the word “sensitive” becomes.

This one is so in-your-face with the specifics of the cause of the anger. The lack of self-awareness becomes apparent as he screams about sensitivity.

The Damned Guy

Clarence Leroy Hinds (1970)

Oil on canvas board, 24” x 14”

Heirloom shared by the Weiner and Heller families

The artist sought to improve upon Michelangelo’s masterpiece by clothing him in a green Speedo and adding a disembodied eyeball over his right shoulder spewing what appears to be toxic slime.

This is a copy of “The Damned Man” who realizes he has been condemned to spend eternity in Hell; one of the hundreds of figures in The Last Judgement, Michelangelo’s fresco on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel.

Neon green Speedo???

Q. Why do you think people are attracted to flawed art and what are a few lessons that people can take away from art that may not be conventionally seen as “good”?

MOBA is fun. It’s not intimidating. No one is going to judge you if you disagree with our judgements. There is always another surprise, another way that a painting went off the rails. Our interpretations are entertaining: often enlightening, clever, pompous, opinionated, or even silly.

People are attracted to MOBA for exactly the same reasons people are attracted to fine art. MOBA art connects you to the artist. It gets you thinking and talking about it. What was the intent? Why was this decision made? How does this make me feel?

Q. Any interesting stories or anecdotes about MOBA artists or controversial pieces?

The Damned Guy

This masterpiece by Clarence Leroy Hinds has been in the Heller and Weiner families since the 1970’s. It was originally given by the artist to his doctor, the late and great Dan Heller who was a dear friend and beloved husband and father.

It is based on a detail from Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel. The consensus in both families is that Hinds did not improve upon Michelangelo’s work.

The Heller family, after a short time could no longer stomach having it in their house, and on a special occasion they gifted it to the Weiner family. The painting began a many-year tradition of being gifted back and forth in creative ways, sometimes involving third parties, ladders, food, vehicles, and carpenters’ tools.

It is for those reasons that the condition of the painting is not pristine.

In 2022, both families decided that it was finally time for Mr. Hinds’ creation to move on to a (hopefully) final resting place. They told us:

“If the MOBA will have it, we will be happy to donate it. We will not ask anything in return, not even the naming of a gallery or a wing of the museum after us.“

Lucy in the Field with Flowers

In 1996, this image was on the cover of the first MOBA book and was included in a story about the MOBA book in an entertainment weekly in Boston. We got a phone call from Susan Lawlor. She was sputtering and laughing and saying, “That’s my nana.”

She told us that Nana’s name was Anna Lally. When she died, one of her daughters, Auntie, had been living with her for years. Auntie was devastated by the loss, so her fond nieces and nephews commissioned a painting of Nana to be made from two photos. In our painting, it’s unclear whether Lucy is standing or sitting. Now that we’ve seen the photos, we can see why. In one photo Anna is sitting. In the other she is standing.

When the portrait was unveiled, the young people who had paid for it were appalled. But Auntie loved it. She hung on the dining room wall where it remained until she died. At that point, the family lost track of the painting. (To be fair, they weren’t really looking for it.)

6 or 8 years later, Susan spotted the painting in a newspaper. The family were delighted that this portrait was receiving so much attention. They bought dozens of copies of the book and continue to buy any merchandise we create with Lucy in the Field With Flowers.

Q. Moving forward plans for MOBA?

It’s been a long-time dream to have a MOBA exhibition in a traditional, established art museum in the US or elsewhere. We also hope to book more major events around the world like our exhibits in Taiwan, Tokyo, and Quebec City.

We are in early stages of producing a third book and there is a good chance of a MOBA total immersion venue opening in 2024 in the US.

Q. Last, what are your messages to our readers?

Don’t let anyone tell you what art you should like. If you like it, you like it. You are not wrong!

Readers can follow MOBA on Facebook, our website, www.MuseumOfBadArt.org, or through MOBA News (send a note to subscribe@MuseumOfBadArt.org)

MOBA Curator Talks via Zoom can be booked for groups or organizations. There are five programs including The MOBA Zoo, In the Nood, and Oozing my Religion.

Visitors to Boston are encouraged visit us at 1250 Massachusetts Ave, in the Dorchester Brewing Co. The gallery is open every day from 11:30am to 9pm on Sundays and Mondays, 10pm on Tuesdays through Thursdays, and 11pm on Fridays and Saturdays. Beer and BBQ are available. Admission is free.

All Photographs credit: Museum Of Bad Art

Thank you for giving our bad art a glimpse of hope. Art is still art no matter how bad or nice it is. The most important aspect is the effort and sincerity of the artist pouring their heart out. And the engagement that the art brings. By the way mark rotho art is consider bad in my opinion. The only engagement it bring is the dollar behind. By the way, love the insight. Will post in my IG.

Finally, I made time to look up the Museum of Bad Art and react, with a few groans, a LOT of guffaws and dizziness after shaking my head too often. Great concept but, yikes what a plethora of near misses, poor judgement, shared winces, balanced by the artist’s results vs intention. I cannot thank you enough for this, and will go through my own watercolor portfolio and use most of them for some good winter fires next November. Cheers, Ann Getman, Cambridge!