His journey has covered 43,493km so far. Giant Steps: The Remarkable Story of the Goliath Expedition From Punta Arenas to Russia is his book journaling his extraordinary journey.

Karl was kind enough to let me interview him recently.

Q1. One of the common questions when people Google you is – “Where is Karl Bushby now?”. Tell us where are you now and what have you been up to?

I’m currently in Mexico, in the state of Jalisco. I’m here alone but Angela Maxwell, an American woman who has spent over 6.5 years walking her way around the world, will join me soon and we will begin training for a long swim across The Caspian Sea, shore to shore from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan, although I think of it as a long water obstacle crossing, rather than a traditional swim.

By the end of 2019, I was in Turkmenistan and arrived on the border of Iran. With my visa about to expire, I was hurried by my escorts (you need permanent escorts while in Turkmenistan) to Ashgabat. At the border, my journey had been put on pause due to visa issues. I returned to LA to catch up with sponsors.

It has been over 3 years since I left Turkmenistan. My flag is still planted on the border of Iran. But I cannot not be there as I have to abide by visa rules. I must return to where I left to be able to continue. In this case, I am unable to return to that location and so I need to back track to a point on my route from where I will deviate in a different direction.

To continue my journey north bound from Turkmenistan, the only options are:

- Backtracking to Uzbekistan from Turkmenistan, losing almost 700 miles of progress. Then switching north up into Kazakhstan and into Russia. However, I was not allowed to enter Russia from Kazakhstan. We are still not sure I would be allowed back into Russia, remembering Kyrgyzstan, where the fact I was refused entry because of my past interactions with Russia apparently.

- To swim 259km to Azerbaijan from Turkmenistan. It sounds crazy but the crazy plan is now the only plan.

Back in 2019, we were lucky to have been given a 30-day visa through Turkmenistan. It can be tricky to get a visa at all for Turkmenistan. You can have a visa and still be turned away at the border.

All my equipment is stashed in an escort’s garden in Turkmenistan. Communications are almost nonexistent with my escort. There are layers of complexity here.

My original plan was going to Iran. Iran was a hard nut to crack. There was increased tension with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the US. This included talk of war. Plus, I have a British passport, one of three passports not allowed free access to Iran, along with US and Canadian.

Q2. What inspired you to start your Goliath expedition that can only be done on foot after leaving your military service back in the 90s?

As paratroopers we lived on our feet, everything we did was on foot. It was about going the distance, being self-sufficient and always pushing boundaries of physical endurance.

It only natural that in this environment the journey was seen through that lens. It’s hard, ultimately, a real challenge as regards to bike or motorbike.

I know cyclists who have gone from Alaska to Ushuaia in 9 months. It takes 6 years on foot, it’s a whole other world. And if you want to know the world, do it on foot, that way you are much closer to any given environment or culture.

You are very much in the thick of it, much more so than zipping by on a bike. Stand filthy in mud, bleeding from thorns, savaged by insects and burned by the sun, the smells and the visions will never leave you.

Q3. You began your journey in November 1998, that was almost 25 years ago, at a time when technology was not as advanced as it is today, for example, the availability of GPS that would make navigation much easier. When you announced that you were going to walk the world, many people thought it would be an impossible feat. What made you confident that this was going to work despite the many doubts?

Again, very much a product of the army. Confidence will get you everything and everywhere. As young paratroopers, we believed we were bullet proof. A product of remarkable British military conditioning, few do it better.

Not just that, but I had trained in all these environments in the army. Everything from Arctic Norway to the jungles of Kenya, you name it. Physically, I knew my limitations in high resolution, in precise refined detail, having been pushed to my limits constantly.

The basic skills of land navigation had been learned and were known. You don’t need a military background to do this, but in my case, it helped.

GPS was available in the late 90’s. We had used it in the army. I cannot remember if I used GPS in those early days. I remember everything back then being paper maps. Most of the time I’m on roads so it’s not an issue.

However, talking of technology, I left home with a cheap instamatic camera using 35mm rolls of film. I never used anything with a touchscreen until 2013. Sometimes, I must remind people I started this journey back in the last century.

Q4. Tell us your typical day while you are on the road?

A typical day – wake up, eat, pack, walk, pitch, eat and sleep, repeat. It’s mostly a dull routine. You slip into a more natural lifestyle, wake when the sun comes up, sleep when it goes down. There is a reason midnight is called Mid…night. This depends on your environment etc. it was very different in the Arctic. There, midwinter, things are very challenging with limited daylight (almost 3hrs) to almost 24hrs of daylight in late spring.

For the most part, you try to get the walking in the light hours. You have about 7-8hrs on the road with about 1 hour lunch rest midday. The idea is to be off the road and pitched before sundown. I slept everywhere humanly imaginable, in just about every condition and environment imaginable.

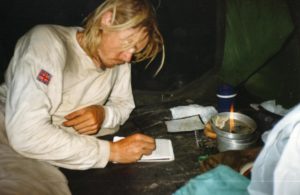

Get in the tent, change clothing into something dry, hang your wet kit to dry. You’re either soaked from rain or sweat. Fire up the stove and cook a meal. After that it’s cleaned up, pack away that stuff you don’t need and turn in for the night. Hopefully, nothing disturbs you and you get a good night’s sleep.

However, being out there somewhere, you sleep very lightly with a mind cognizant of its unknown environment, always an eye open for dangers.

The route was generally well understood long ago. The entire route works on a ‘route corridor’ concept. Basically, a broad line on a global map that might incorporate a few detailed route options. On the ground, the route is refined from one waypoint (a large town or city) to the next waypoint (the next large town or city) that might be a few days or weeks apart.

The daily distance is about 30kms. This was established in the early days as the optimal daily distance. Beyond that I tended to struggle and blister, and it would be difficult to maintain. 30kms I was able to maintain long term.

As for equipment, it depends on the environment and season, it can vary dramatically. However, I tend to travel with everything I need for winter and summer. That’s why I tend to travel heavy compared to most travelers, that’s because I will continue from season to season. My tents are 4 season and 4 season sleeping bags.

Q5. I understand that you have had several run-ins with the Russian authority, including being detained by them for not entering Russia at a correct port-of-entry. Tell us what other harrowing experiences have you had on your journey and what situations usually frustrate you the most?

Yes, Russia and having to deal with the Federal Security Service (FSB) was less than pleasant. It’s not the first time I was detained. On crossing the border of Colombia into Panama I was detained by Panamanian police. The border region was closed due to the war with Colombian guerrillas FARC.

The border region was a notorious mountainous jungle known as the Darien Gap. The jungle, named after the Darien national park on the Panamanian side of the border, was controlled by FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Fighting both the Colombian army to the south and Panamanian police to the north.

It’s a very dangerous and complex place and once I made it through to the Panamanian side, I was picked up by the police and held in jails for 18 days until I could clarify who I was and what I was doing and allowed me to continue.

Other major challenges have been the 2008 financial crisis that meant I was not able to return to Russia after losing sponsors. That cost me 3 years before I was able to afford returning to one of the most expensive sections of this journey, far northeast Russia. Then a visa ban from the Russians, as we never were able to get along after crossing the Bering Strait. I was forced to spend a year walking across the US from my sponsor’s base in Los Angeles to the Russian embassy in Washington DC, the year before that was spent trying to negotiate with Russia over the ban, that got us nowhere.

However, the media campaign during the walk across the US paid off and we found a fan in the Russian embassy that was willing to offer me a visa to return and continue through Russia. That cost me more than 2 years in total.

It has been over 3 years since I left Turkmenistan and returned to Uzbekistan. The most painful and difficult challenges have been dealing with the loss of relationships. I have fallen in love twice and lost both due to this journey. That has taken its pound of flesh and then some.

Q6. How do you find your sponsors for your expedition?

The short answer is I have never found sponsors. The sponsors I have found me. No attempt by me to find sponsors has ever worked. I don’t believe anyone ever even responded to a request.

In the years before the journey began, I tried soliciting the help of companies to get onboard and got nowhere.

A company named Superfeet, who made footbeds, gave me a free set of fitted footbeds at a trade show in the UK and I used them all the way to the US border. Which paid off after 4 years of the journey. In Tucson, Arizona, I found a shoe store with a Superfeet rep. I showed him my footbeds and the fact they had covered 10,500 miles and outlasted 9 pairs of boots. He almost had a heart attack. Superfeet got onboard and helped to fund my time through North America.

Before the US border I never had any financial support other than some handouts. Those were rough days, but we always understood I could do that. You can survive in Latin America with a pocket full of rice, that’s not so easy in North America.

It must be said I could not have done South America without the help of locals. And it’s not just South America. They fed me, watered me, and even nursed me back to health when I was sick.

Having read about me in local papers, people would stop and offer me cash on the roadside, people from the complete economic spectrum. Even drive hours to find me and feed me. I’ve been privileged to have one of the most amazing global support systems imaginable – human kindness.

And the further north you go, the tougher things get. Before the journey began, I understood the turning point would probably be the US border. All I had to do was get there.

And that’s exactly how it played out. Also, at the US border we were contacted by a Canadian website hosting company who offered to host our website and toss some cash into our account.

These were small amounts of money but a huge deal for someone who had no idea how I could survive in North America without any money.

Of course, what was happening was that we were entering an area of commercial interest to outdoor companies etc. the US had a huge outdoor market unlike Latin America at that time. Suddenly I was of some value. I had a marketable history, stories etc so all this lends itself well for marketing to their target audience. But like I said, they pretty much found me.

On the way north, my father back in the UK had luck finding a book agent and a ghost writer and they turned my many years of journal keeping into a book format.

We managed to get an advance of payment on the book deal with TimeWarner to cover the expensive cost in the Arctic, where you need special equipment, special food and fuel supplies and buckets and buckets of expensive logistics spanning Alaska, crossing the Bering Strait and Far Northeast Russia. We got very lucky. After the financial crisis of 2008, things looked grim. The money had run out and I had left North America for Asia, so there was much less interest from relevant commercial companies.

From Asia I traveled to Mexico and stuck in Mexico for over 2 years, when the financial crisis was over, an individual with a media company found my book in a bookstore. With a passion for adventure, he was surprised he had never heard about me before.

He tracked me down and flew to see me. Days later, I was in LA talking to a few guys that believed they could get me home and fund it using the entertainment industry.

Westward Productions was formed and my newfound friends, documentary film makers and show runners issued me with a few cameras and got me back on the ground, up right and moving forward. I’ve been backed by Westward ever since 2010.

Q7. One of the highlights of your expedition was crossing the Bering Strait from Alaska to Siberia on foot in 2006. Tell us about that expedition?

Well, none of it is fresh in my mind now, all seems so long ago. As I moved north through the Americas and the gravity of the situation became ever clear – it did not look good. In Alaska everyone we spoke with simply dispelled the possibility of a Strait crossing as madness, especially the experts.

Many experienced expeditioners had failed attempts. I was an outsider with little to no polar experience. Once I had made it to the west coast of Alaska, having had my ass whooped that winter in the Alaskan interior, I learned two explorers – A Danish arctic adventurer who had done both north and south pole expedition along with a US mountaineer had tried to reach Russia from Alaska the year before. They had been rescued after six days.

By now I had teamed up with Dimitri Kieffer, a French US citizen and adventure racer who decided to join me on the Bering Strait attempt. We simply studied what everyone else who attempted the crossing had done and made seemingly obvious adaptations.

Our approach would have to be lighter, faster, and more direct. We would have to become human Arctic marine mammals, able to work in the semi frozen water as well as out. Be willing to swim as much as walk. The environment simply demanded that of us.

There was no trying to avoid open water in a baffling ever changing maze of shifting ice. You had to punch through. Let’s be clear, not even I believed we would make this first time. The day we stepped onto the ice, the two things foremost in mind “how do we get off this thing alive and how the hell do I afford this next attempt next winter?”.

I was pretty much convinced we would bounce off this first attempt like a brick wall. Lick our wounds, learn, and try again. Eventually getting it right.

We made history on the first attempt, surprising ourselves in the process. The most unforgettable moment was walking onto Russian land and making a call on the satellite phone to my father telling him I had Russian dirt in my hands.

Q8. This is the continuation of the previous question. I know you are planning to swim across the Caspian Sea, from Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan. What did the Bering Strait crossing teach you that you can use as a lesson to better prepare for this challenge?

For the Caspian, yes, it’s somewhat like the Bering Strait as you face a challenge far from your comfort zone. I’m not a swimmer, I don’t even play in the water, never my thing, not keen on it at all.

The first time I even considered it was out of jest in a long-forgotten conversation, it was literally out of jest. Plan C was madness. Yet here we are looking at the logistics of a 259km swim. I happen to be based on the pacific coast of Mexico with a bay almost 4 kms wide so I have a good training ground for a beginner.

Physically I can swim 8kms in 6hrs, but when I say swim, I’m not talking about the swimming you are now constructing in your mind’s eye. The traditional Michel Phelps style with goggles and speedos. Not at all, I could barely get 50 feet that way, I hate it, and I’m not going to become Michel Phelps in a few months.

I must find the right approach, something I can sustain over a long-time frame over many days. If I can swim 10kms a day, that’s 25 days in the water. If you’re a marathon swimmer right now, you are thinking “meh…ok doable”.

If like me, a non-swimmer who is very unhappy in the water, it means sleepless nights and loss of appetite. Right now, I’m doing backstroke with a flotation jacket and kicking with short swim fins. That gets me the 8kms over six hours in a very good state. I can maintain that for a long time.

The other interesting conversation that has come out of this are the rules. The journey is defined by two rules that cannot be broken. Rule number one: I cannot return home until I arrive on foot. Rule number two: I am not allowed to use any form of transport to advance. So, the first question is – what can I use to assist me in getting across the Caspian Sea?

My sponsors wanted me to use something akin to a surfboard and paddle across. However, to me this could be classed as a boat. I have to be in the water. We can use floatation devices including small boards if most of me is in the water. Can I use the wind? Like a drogue chute to catch the wind and pull me while in the water?These are the types of questions we are grappling over right now. I won’t be alone in this, Angela Maxwell, another US world walker is going to join me on this next leg of the journey. She will join me here in Mexico in November where we will train together and perhaps test some of these ideas.

The plan is to return to Uzbekistan in March. We then have 1,000 miles North and west to the Kazakh coastline. By August we should be ready to swim, this appears to be the optimal month.

We just started a website to follow this process: https://www.westboundhorizons.com/

Q9. After walking the world for 25 years, what do you think are the most significant changes in your mindset?

It’s hard to specify how a mindset has changed, while I would say for sure a lot of changes when you are exposed to the world on this scale. But also, we all change as we get older, 25 years is a long time. You stop being locally focused, your interests or concerns stops being your region or your country and takes on a more global flavor. You scale up from the small cycles most humans live in, our home, workplace, local bar, sports stadium.

Also, over time, and having traveled the Americas bottom to top, I noticed the distinct lack of science literacy. This I found a little disturbing, hence the motivation to pursue a nonprofit as a response.

Q10. You are always on the move for over 20 years. What do you do when you are not walking?

Coffee shops. I’m partially joking, for the most part there is always something to be done, if I’m static then first is trying to move. Once you realize you are unable for whatever reason and have to wait, which becomes all too clear mid-2020, then you are still trying to work the problem.

There is always a way, you just need to find it or invent it. On the days when you are not doing that then I have another interest I throw my weight behind.

Some time ago I started a nonprofit to invent creative ways to help bring science literacy to the public, or rather bring the public to the sciences. Science literacy, or rather the lack of, is my other passion. I used my walk across the US in 2013-14 to get a good look at how this fight was being fought on the front lines of education in the US.

I spoke to a lot of educators, visited a lot of programs etc. all the way from the west to east coast, from sea to shining sea. Once in DC, I took that information and decided on a plan of action. In the informal education realm, it appeared robotics, make it labs and coding were well taken care of, however, I noticed a gap in the creative use of aerospace simulation.

Considering we stand on the precipice of a new era of human space exploration, and with massive advances in entertainment technology bringing a full spectrum aerospace experience to the public is a very good and exciting window into the sciences and a very interesting way to capture the imaginations of the young.

My organization focused on three challenges identified by educators and government I learned while crossing the US. All three can be applied to the world in general. 1. The need for greater emotional engagement. 2. The need for long term engagement (long term programs) to mitigate ‘Single event exposure’. 3. The need for greater exposure to these programs, better accessibility for the public. So, we set about designing a way to tackle those problems. That keeps me busy when I get the chance. https://www.asimetric.org/

Q11. First thing that you will do when you go back to your family in Hull, England after decades of walking?

Cup of coffee, then shift gear to the nonprofit side

Q12. What are your words of wisdom to our readers who might be contemplating a similar expedition?

The world is a nicer place than TV tells you and humans are incredible. Confidence will get you anywhere. Dream bigger than your fears grant you permission. Live, because you’re dying, remember to bring a friend, or a billion. Run as fast as you can because we all need more time, relatively speaking.

All photographs credit: Karl Bushby

I sensed the great aloneness and bravery travelling alone. As a reader, I am scare if that were me, but the idea of travelling and conquering the fear of loneliness is not something even a mere human can do. It is indeed David defeating Goliath kinda story. Please continue to inspire.