For a information about each camp’s location & details, hiking time, and elevations please see the Itinerary section in this guide.

Our base camp was located around 5000 feet. We spent one night here. We drove into the camp from Arusha late at night in large land rovers. This camp was about 4.5 hours from downtown Arusha. Once off of the pavement about 1 hour outside of Arusha we drove on dirt roads to the camp. We drove through deep puddles and muddy roads. At one point we were about to drive through what looked to be a very deep muddy river with steep banks on both sides, but Roger (probably short for something much less palatable to the western tongue) floored it and fortunately we splashed our way through without becoming stuck. Upon arriving in camp we promptly were treated to a warm meal and then immediately after, fell into a deep sleep.

We had an entire rest day where we took some short hikes, read, and photographed the greenery of Kilimanjaro’s flanks. Base camp had permanent tents with comfortable beds and bucket showers.

Our lead guide’s name was Kampana, which means “little rat” in Swahili. He woke us up the next morning at 5am and by 5:45 we were on the road. All our gear was stuffed in with us or stacked high on the roof. We drove for 3 hours on dirt roads until we arrived at the west park entrance. Upon arrival we were met with extremely muddy roads and a relentless rain that never let up. We quickly signed in our names and passports and then hopped back in the land rovers for more driving in the mud.

After about another hour of driving, the road became extremely muddy and much more steep. We had three vehicles, a lead, middle and a trailing. Finally the mud became so deep and the road so steep that our lead vehicle became hopelessly mired in the muck. We happened to be driving through a small village. The villagers came pouring out the mud huts and the men ran up to the lead vehicle and began frantically using their machetes to wildly cut down any piece of organic vegetation in sight. Then they began to throw leaves, branches and organic muck into the muddy tire ruts and around the stuck vehicle.

While that was happening all the children gathered around the other two vehicles looking curiously at the western faces. A video camera popped out of one of the windows and the children began laughing hysterically. They were amazed after they saw themselves played back on the video camera screen.

Meanwhile, driving up the steep long muddy hill took about 2 hours for all three jeeps to successfully navigate the miserable driving conditions. Dave was chilling in the trailing vehicle laughing to himself at the bad luck of the first two vehicles when the wheels began spinning and all forward momentum stopped as the jeep rocked back and forth deeper into the ruts of its own making. Ten minutes later Dave was out stuck in the knee-deep mud helping to push a 3500-pound vehicle up a steep hill.

Finally with enough people pushing the heavy vehicle it began to slowly inch forward and finally reached a flat area; we left the vehicle and continued on foot to the trailhead. We finally arrived. Mud was everywhere. People were milling about. Gear was left sitting in the rain. Our guides ushered us towards the trailhead with a sense of urgency in their voices. Finally, we were beginning our climb of this 19,340 foot giant, which was nowhere in site and would not be for another 3 days.

Greenery rose above and all around us. Tangled vines dripping with heavy moss hung heavy. This was the jungle that grew on the lower slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, but we scarcely noticed. The beginning of the trail was very steep and muddy and members of our group struggled to maintain their balance. We hiked for 2 hours and arrived at our lunch site. Ravenously we ate. One hour later we continued on as the rain beat down on us with a frenzy that was not easing. This climb was attempted in late December. Tanzania has two wet seasons in a year, the long wet season and the short wet season. In most years late December means the end of the short wet season. This short wet season was abnormally wet and we greatly suffered through it.

Greenery rose above and all around us. Tangled vines dripping with heavy moss hung heavy. This was the jungle that grew on the lower slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro, but we scarcely noticed. The beginning of the trail was very steep and muddy and members of our group struggled to maintain their balance. We hiked for 2 hours and arrived at our lunch site. Ravenously we ate. One hour later we continued on as the rain beat down on us with a frenzy that was not easing. This climb was attempted in late December. Tanzania has two wet seasons in a year, the long wet season and the short wet season. In most years late December means the end of the short wet season. This short wet season was abnormally wet and we greatly suffered through it.

Upon climbing up to our 2nd camp at about 9000 feet we arrived to find a lot of our gear sopping wet. The rain finally let up and we laid everything out to dry in the fast disappearing rays of sunlight.

I will take this opportunity to explain the inner workings of our group. Our team included one head guide, 5 assistant guides, 6 cooks, 34 porters, and then 12 clients – for a total of 58 people. After the 12 clients began hiking, the porters and cooks would frantically clean up the camp area, and then race by us on the trail in order to set up the next campsite. This system always worked, as everything was set up for us when we arrived in time for mid-day meals or camping. Mid-day meals were under a mess tent with small stools gathered around a long table. The tent was often necessary to keep out the driving rain or at the higher elevations, the snowfall.

On climbs such as these there are always faster people forging ahead and slower people (for whatever reason) lagging behind. Group dynamics become extremely important, and if the guides are not superb and know how to handle specific situations, problems may arise.

By midnight of the 2nd camp I was in bad shape. We were camped at 9000 feet and already I had terrible altitude symptoms. This was quite strange because I had slept above 9000 feet many times and never had any problems with the altitude. I could hardly stand up and walk to the bathroom. I was very dizzy and seemingly getting weaker. By morning I felt a little better, but not quite perfect. I mentioned my condition to the head guide and he said he would keep an eye on me.

We started hiking and I felt fine until about a mile into the hike. I started becoming quite dizzy and much weaker. This condition worsened as I continued to hike. At 10am I caught up to the group who was waiting for me on the top of a hill. They looked at me – worry clearly showing on their faces.

From here the trail, and I, went downhill, although my physical condition kept going downhill even after the trail began to ascend. The rain began to fall and by this time I could barely stagger upright. The head guide stayed with me while the others in the group forged on ahead. Fortunately he had the insight to send out word to several of the other guides that I couldn’t walk, and would need to be carried or dragged into camp. After sitting on a rock in the cold rain for about an hour and throwing up at random intervals, several guides appeared out of the mist and began to help me inch forwards. Unfortunately we were climbing a steep part of the trail so we moved very slowly.

The rest of the group reached Camp II by early afternoon. The guides half dragged and half carried me. At one point they would put me on their back and walk with me until they became tired and another guide would take over. I made it to camp just after dusk and was promptly deposited into the warmest tent in camp, the cooking tent. Immediately I fell into a deep sleep.

The next morning I woke from my sleep and felt much better although I was still quite weak.

My condition for these 24 hours can be directly attributed, not to altitude, but to a severe reaction to the altitude-inducing drug Diamox. I was part of a small percentage of people who have a reaction to this drug. My symptoms were characteristic of a typical drug reaction; ringing in the ears, dizziness, and loss of balance. At this point I was told to stop taking the drug by just about everyone in the group. If you ever take Diamox before climbing a tall mountain and you have never used this drug previously, I highly recommend taking a few dosages before you actually leave for your climb. Give yourself a couple of weeks before departure, so that if you do get a reaction, you have time to recover.We had steady rain during the trek for the first 3 days. During the next few days we had sporadic rain during the day, turning to snow and sleet at the higher elevations. By the end of the climb towards the upper reaches of the mountain the weather was generally fair and precipitation was at a minimum.

During the next few days I was a little weak but fortunately I was able to walk on my own. I always was the last one into camp. As we climbed higher we left the lushness of the jungle far behind. We entered the heath zone, a mix of bushes and grass, but no more trees. As we climbed and the weather slowly improved we were rewarded with outstanding views of Mt. Meru. This mountain is approximately 16,000 feet tall and sits right next to the town of Arusha. Each morning the skies would be clear above our campsite and we would watch a thick layer of clouds hovering around the base of Mt. Meru slowly ascend up to our elevation and then quickly cover us. Soon after it would begin to rain or snow.

Our guides had miraculously packed in bottled water for the first day and a half. This was tremendous weight and unfortunately did not last long. Soon we were using pills or filters to purify our water. Most of the water sources were quite dirty and often the filters would become clogged with sediment. I highly recommend taking 2 Nalgene hard plastic (Lexan) water bottles with you. On some days you will find the streams are far and few between and it is always best to have some water with you.

Our 3rd night was spent at Lava Camp, just below a rock formation at 14,500 feet called Lava Tower. The hike from Lava Tower to the Arrow Glacier camp at 15,500 feet was a short day and took only about 3 hours. Granted we did hike in near zero visibility through a snowstorm, but the distance that day was fairly short and steep.

Arrow Glacier Camp is situated on several snowfields with many rocks showing through the snow and ice. From this camp you could look straight up at the sheer side of the upper flanks of Kilimanjaro. You could see exactly where you would be hiking the next day. It was a scary, yet at the same time, an impressive sight.

Hiking the next day began around 6:30am. For the first time on the climb – I felt great, strong, and full of energy. I led the team for several hours up the steep face of the mountain. At times we were on all fours, at other times we would carefully pick our way up rocky chutes, and at other times we would stop and admire the incredible view from 17,000 feet up into the African sky. Mt. Meru was clearly visibly probably only 40 to 50 airline miles away. It was a mostly clear day, and we were at the elevation that kept us just above the cloud layer. This was a great day for photographs. At this elevation the clouds become more distinct, more powerful taking on a light pink sheen that I have only seen from an airplane.

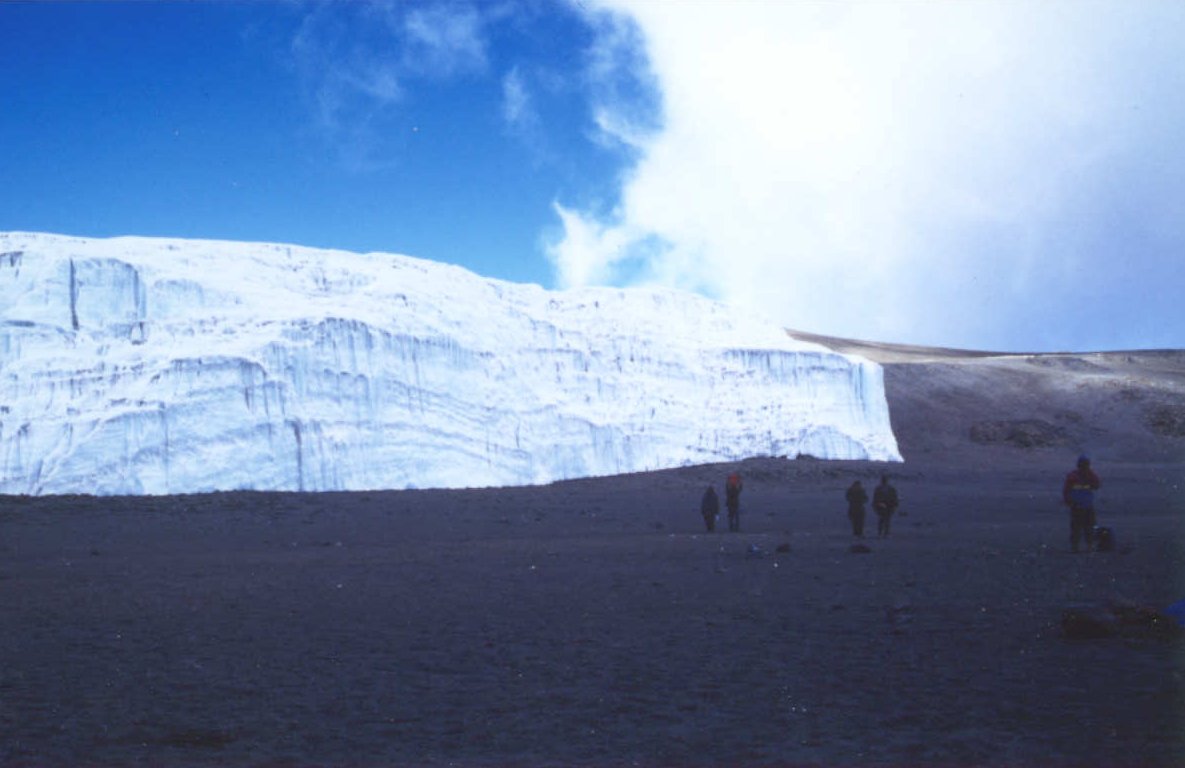

Once we hit 18,000 feet I went downhill quite rapidly due to the effects of the high elevation. I again had all the symptoms that I had from my earlier reaction to Diamox. I slowed down and the entire group passed me. Once again I was taking up the rear with a guide. I struggled up the steep rock outcroppings. At this elevation it takes a lot of energy to put one foot in front of the other, especially up a steep incline. Just before the crater rim I began to vomit. I reached the crater rim and promptly threw up, but not before I caught an impressive view of a stark landscape. I saw 50 to 100 foot tall walls of ice from the edge of the glacier in contrast to the start moonscape looking volcanic plateau of the crater rim.

At this elevation nothing visible grew, no plants, grass, or trees. Upon closer inspection one might be able to find some lichens, but in my sick weakened state I forgot to check!

I had just enough energy to fall into a tent upon arriving at high camp at 18,500 feet. I quickly fell into an altitude-induced stupor and lay without moving all night. I was only wakened once and that was at midnight by guides banging on pots and pans and yelling “happy new year” and “happy millennium.” I mumbled, “great”, and fell back to sleep. By morning I was so weak, could barely stand, and was quickly becoming disoriented, so the guides dragged me out of my tent and threw me into a HAP bag (high altitude pressure body bag). A HAP bag simulates the effects of lower altitude. This was a very narrow bag made of thick plastic with a small clear plastic window, with just enough space inside to fit one person. I spent about an hour and a half inside this claustrophobic bag. The guides slowly increased the air pressure inside the bag and I began to feel somewhat normal again.

As soon as they released the pressure and unzipped me from the bag I realized just how terrible I had been feeling. The altitude sickness grabbed me almost immediately and with a worried look on his face, the head guide instructed me to get down the mountain as quickly as possible.

I left immediately with two guides supporting me, one on either side of me. At this point the rest of the group left for the summit. I on the other hand headed in the opposite direction across the vast plain of the crater stopping every minute or so to rest or throw up. The glistening of the silvery sands topped with a thin layer of frost was so bright I left my glacier glasses on at all times. We hiked for about an hour across these sands until the trail ascended steeply to the top of the crater rim before it would ultimately descend down the mountain on the other side.

Unfortunately the trail wound up to 19,000 feet before it descended. This was bad news for me. We began to cross a lengthy snowfield to Stella Point, which is located at 19,000 feet. What would have normally taken about 10 minutes to climb at sea level took me about an hour.

I finally reached Stella Point, promptly threw up, felt better, and glanced towards another trail leading to the summit located only 340 vertical feet away. I thought to myself that there would be no other chance to make the summit later. I mentioned to the guides that I was interested in climbing up. They said ok, lets go.

I left a crowd of people sitting around Stella Point. I found out later that two people had died at Stella just after I arrived, because they did not descend after contracting serious altitude symptoms and they had climbed the mountain using the coca cola route..

The trail from Stella Point to the summit was a gentle climb, but at 19,000 feet + every step took a lot of energy. I passed people on the trail who yelled encouragement. Finally I reached the summit and again promptly threw up. Afterwards I felt strong enough to snap a few photographs with the famous sign. I spent about 10 minutes on the top compared to the 1 hour + that most of our group had enjoyed earlier. I missed out on the group shot but I was very glad to be on the top.

We left and as I descended I could feel my body slowly gain energy. By about 13,000 feet I was running down the trail as fast as I could go. I was shooting by guides, porters, and clients. By 3:30pm I was at camp at 10,000 feet. This was quite amazing considering I was at the summit at 19,340 feet at 10:30am!

The camp I stayed in looked like a refugee camp. Garbage, tents, and people were strewn all over the place. It was the main camp for those going up and those going down the mountain. One night was all I could take of this place.

We then left early in the morning. This last part of the hike was a mud festival. At times I was knee deep in the glop. I was covered in mud by the time I arrived at the entrance gate around 7000 feet.

Despite all the personal hardships I experienced, I would recommend this climb to anyone who is in decent shape. Some prior experience at higher altitude is highly recommended, so that you have some knowledge of how your body reacts. This would be helpful before considering a climb of this magnitude.

I know of people in there 60’s and 70’s who successfully climbed this mountain. If you want to avoid the horror stories that I heard from other climbers with other groups choose your guides wisely and carefully. The main thing is to do some research. You will pay more for your trip, but based on personal experience, it is definitely worth the extra money.

Leave a Reply