Working as a tour guide in Philadelphia’s historic district, I must have become a little Pennsylvania-centric on my view of the American Revolution because I was absolutely stunned when I stumbled upon the Trumbull Room at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut. It was the thrill of unexpectedly running into dear acquaintances while on vacation – the familiar blue and yellow uniform in the painting of my favorite founding father, General George Washington at Trenton by John Trumbull, a striking contrast to the bright red walls of the gallery. At almost eight feet high, it’s as intimidating as standing in front of the General himself! And one over from it – even the memory leaves me breathless – the iconic Trumbull painting The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776. The original! The collection is fantastic. Trumbull, coupled with Roger Sherman and Hale at Yale, make this city a must-see for any fans of the Revolutionary Period. Indulging in it all felt almost decadent!

Working as a tour guide in Philadelphia’s historic district, I must have become a little Pennsylvania-centric on my view of the American Revolution because I was absolutely stunned when I stumbled upon the Trumbull Room at the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut. It was the thrill of unexpectedly running into dear acquaintances while on vacation – the familiar blue and yellow uniform in the painting of my favorite founding father, General George Washington at Trenton by John Trumbull, a striking contrast to the bright red walls of the gallery. At almost eight feet high, it’s as intimidating as standing in front of the General himself! And one over from it – even the memory leaves me breathless – the iconic Trumbull painting The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776. The original! The collection is fantastic. Trumbull, coupled with Roger Sherman and Hale at Yale, make this city a must-see for any fans of the Revolutionary Period. Indulging in it all felt almost decadent!

I spent so long in the Trumbull Room that the security guard twice asked me if I was all right before filling me in on some of the museum’s history. He told me that Trumbull, a Connecticut native, donated a collection of his paintings, including his Revolutionary War series, to get the museum started. The transaction included the stipulation that Trumbull and his wife be buried beneath the gallery – or the paintings would be moved to his alma mater, Harvard. Yale doesn’t want to lose this treasure! The guard said that in keeping with the agreement, the Trumbulls’ remains have been moved a few times as the collection’s location changed. The communications department of the museum corroborated his story. The Trumbulls’ gravestone that I saw on the first floor of the Old Yale Art Gallery building, where the Ancient Arts and Coins and Medals exhibits are, marks their previous resting place. Their ‘final’ resting place (at least for now I guess!) is indicated by another marker on the lower level of Street Hall in the library of the Nolen Center for Art and Education, under the Trumbull Room that I had the pleasure of exploring. According to Communications Director Joellen Adae, “The Trumbulls did not have children, and John came to think of his paintings as his children in the sense that they were and are his true legacy. He did not wish to be separated from them.” A touching tribute to a proud papa.

Trumbull’s Revolutionary War series consists of The Battle of Bunker’s Hill, The Death of General Montgomery at Quebec, The Declaration of Independence, The Battle of Trenton, The Battle of Princeton, The Surrender of General Burgoyne, The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, and Washington Resigning His Commission. There are also several miniature portraits of important figures in eighteenth century American society on display, including a delightful set of women which includes Martha Washington, her granddaughter Nelly, and two daughters of Philadelphia judge Benjamin Chew. (His estate Cliveden played a significant role in the Battle of Germantown and has been preserved as a landmark.)

Extremely helpful is a book available in the exhibit hall which indicates in a paint-by-numbers fashion who  all of the historic figures are in the paintings. Most students of Revolutionary era history can identify the Committee of Five assigned to write the Declaration of Independence (at least Adams, Jefferson, and Franklin standing in front – Livingston and Sherman might be more challenging), but pointing out the other representatives present is daunting. I was especially happy to locate the Pennsylvania delegation which includes Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution who died in bankruptcy, another of my personal favorites. Trumbull exerted great effort to paint as many of the representatives from life as he could. Others he painted from a likeness or used the person’s son as a model, and if a likeness couldn’t be obtained, the man wasn’t included. For some of these men, the Trumbull image is the only one of them that exists.

all of the historic figures are in the paintings. Most students of Revolutionary era history can identify the Committee of Five assigned to write the Declaration of Independence (at least Adams, Jefferson, and Franklin standing in front – Livingston and Sherman might be more challenging), but pointing out the other representatives present is daunting. I was especially happy to locate the Pennsylvania delegation which includes Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution who died in bankruptcy, another of my personal favorites. Trumbull exerted great effort to paint as many of the representatives from life as he could. Others he painted from a likeness or used the person’s son as a model, and if a likeness couldn’t be obtained, the man wasn’t included. For some of these men, the Trumbull image is the only one of them that exists.

These smaller paintings of his are considered his finest work, better than the large-scale copies he made for the Capitol in DC. I’m not much of an art critic; I just love being able to experience the originals, up close with no glass or case obstructing my view. To know that each brush stroke was made right around the turn of the nineteenth century, when we were forging our way as a new nation. The future was uncertain, but John Trumbull had served as an aide-de-camp to Washington and a colonel in the war – he knew these paintings were important. In integrity, he committed himself to rendering the spirit of the events with all of the humanity involved, from his perspective as a participant in it. The man whose inspiration had created the canvases before me had met John Singleton Copley, studied under Benjamin West, and shared a painting room with Gilbert Stuart. If all of that brush with artistic greatness wasn’t enough, he was almost hanged as an American spy in retaliation for the death of British spy John Andre; stayed with Jefferson in Paris to collaborate on The Declaration of Independence; and had an audience with James Madison to pitch his large-scale works in the Capitol. I was only one step removed from all that magnificence!

Not only I am linked to the brave and brilliant men who founded our country – all of us are. Anyone who has ever seen a Trumbull painting, any of them – in the past, present, or future – is linked to the spirit that is the American DNA. Not an ethnicity but an idea, a longing for liberty and freedom that was and is made real for us today, with all of its complications, by the efforts of these men. They truly are our forefathers. I was moved by the immediacy of the connection, by the wonderful power of art to bridge time and space, to unify.

The Trumbull Room has other amazing works as well – an evocative portrait of Connecticut statesman Roger  Sherman posing awkwardly in a homespun suit; John Singleton Copley portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Smith exemplifying the wealth of the merchant class on the eve of the Revolution; famed architect William Strickland exuding the breezy air of a romantic poet in front of his Philadelphia commission, the Second Bank of the United States. I wanted to grab that one and take it back to Philadelphia with me! Today the Second Bank is one of my favorite tour stops – a portrait gallery featuring a substantial number of works by Charles Willson Peale, and a few of his works are also on display in the Trumbull Room. My favorite is the life-size rendition George Washington at the Battle of Princeton. I really did feel the pleasant surprise of reconnecting with old friends in an unfamiliar place.

Sherman posing awkwardly in a homespun suit; John Singleton Copley portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Smith exemplifying the wealth of the merchant class on the eve of the Revolution; famed architect William Strickland exuding the breezy air of a romantic poet in front of his Philadelphia commission, the Second Bank of the United States. I wanted to grab that one and take it back to Philadelphia with me! Today the Second Bank is one of my favorite tour stops – a portrait gallery featuring a substantial number of works by Charles Willson Peale, and a few of his works are also on display in the Trumbull Room. My favorite is the life-size rendition George Washington at the Battle of Princeton. I really did feel the pleasant surprise of reconnecting with old friends in an unfamiliar place.

The Yale University Art Gallery is free, as is the Yale Center for British Art. There is absolutely no reason not to visit! In the Center for British Art, I found a wonderful John Singleton Copley portrait of a young boy, Richard Heber, with a cricket bat and all the trusting expectancy of youth. (Copley was a leading American  painter, perhaps most famous for his portrait of Paul Revere that is strikingly similar to the Sam Adams beer logo.) Even more impressive to me was a Benjamin West portrait of himself and his family. He, his wife, and children shimmer in their luxury, in sharp contrast to the stark simplicity of his Quaker father and half brother. Benjamin West, while American, moved to England and gained favor with the king. The painting seems to me to serve as a visual essay on the identity of the self-made man – a product of upbringing, hard work, talent – a possibility more easily attained in the diversity and freedom of the American colonies.

painter, perhaps most famous for his portrait of Paul Revere that is strikingly similar to the Sam Adams beer logo.) Even more impressive to me was a Benjamin West portrait of himself and his family. He, his wife, and children shimmer in their luxury, in sharp contrast to the stark simplicity of his Quaker father and half brother. Benjamin West, while American, moved to England and gained favor with the king. The painting seems to me to serve as a visual essay on the identity of the self-made man – a product of upbringing, hard work, talent – a possibility more easily attained in the diversity and freedom of the American colonies.

Another joy was learning about Connecticut statesman Roger Sherman, the only man to sign four of the United States’ founding documents: the Articles of Association (establishing the boycott against British goods in 1774), the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. (Philadelphia’s Robert Morris was the only other man to sign the Declaration, Constitution, and Articles of Confederation.) I went to the site of Sherman’s house (no longer standing) where the Union League Cafe is now. The plaque honoring him states that in addition to being a founding father of the country, he was also the first mayor of New Haven, a treasurer at Yale College, and a Congressman for 20 years. Washington visited him at his home in 1789.

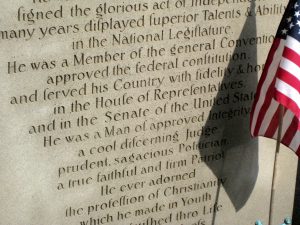

I love the sacredness, the peaceful repose of cemeteries and generally make an effort to visit any in the vicinity when I’m  traveling. Roger Sherman’s grave is at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, the first in the country designed with family plots. In 1941, over 200 of his descendants dedicated a new marker to save the text of the original table stone which was no longer readable. It’s a great study in the now extinct long ‘s’! (It looks like an ‘f’ except the cross bar doesn’t go all the way through. It was only used lower case and in the beginning or middle of a word.) I was so happy to find his burial spot and take a moment to pay my respects. The cemetery is also home to the graves of cotton gin inventor Eli Whitney, ‘Father of Football’ Walter Camp, and Noah Webster of dictionary fame. The Egyptian-style entrance is also impressive. Besides Roger Sherman’s grave, I found most interesting the markers honoring those buried in the seventeenth century a few blocks away at New Haven Green. There is a plaque for the only Mayflower pilgrim who died in Connecticut as well as for one of New Haven’s original settlers.

traveling. Roger Sherman’s grave is at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, the first in the country designed with family plots. In 1941, over 200 of his descendants dedicated a new marker to save the text of the original table stone which was no longer readable. It’s a great study in the now extinct long ‘s’! (It looks like an ‘f’ except the cross bar doesn’t go all the way through. It was only used lower case and in the beginning or middle of a word.) I was so happy to find his burial spot and take a moment to pay my respects. The cemetery is also home to the graves of cotton gin inventor Eli Whitney, ‘Father of Football’ Walter Camp, and Noah Webster of dictionary fame. The Egyptian-style entrance is also impressive. Besides Roger Sherman’s grave, I found most interesting the markers honoring those buried in the seventeenth century a few blocks away at New Haven Green. There is a plaque for the only Mayflower pilgrim who died in Connecticut as well as for one of New Haven’s original settlers.

One of my most fortuitous finds was a note in something I read at the Yale University Art Gallery mentioning the statue of Nathan Hale on Yale’s campus. I had to find it! I read about Hale, the first American spy to be executed by the British during the war, in the Alexander Rose work, Washington’s Spies (the book on which the television show Turn is based). Hale also made an appearance in an episode of Sleepy Hollow. His story is so sad – an amiable, good-looking Yale graduate; an idealistic patriot willing to spy for his country when it was seen as dishonorable work; his inexperience leading to his capture; his strength and courage before his death. Whether or not he really said, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country,” he clearly said something significant that impressed the British, something to the effect that our country and its ideals were worth fighting for. I found the statue outside the dorm he lived in while at Yale. Nathan Hale, Class of 1773. He was a recent college grad, just as I was once, excited to embark on the new adventure of his life. Does anyone’s life turn out as he or she had planned? Would that all of us could meet disappointment with such grace.

One of my most fortuitous finds was a note in something I read at the Yale University Art Gallery mentioning the statue of Nathan Hale on Yale’s campus. I had to find it! I read about Hale, the first American spy to be executed by the British during the war, in the Alexander Rose work, Washington’s Spies (the book on which the television show Turn is based). Hale also made an appearance in an episode of Sleepy Hollow. His story is so sad – an amiable, good-looking Yale graduate; an idealistic patriot willing to spy for his country when it was seen as dishonorable work; his inexperience leading to his capture; his strength and courage before his death. Whether or not he really said, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country,” he clearly said something significant that impressed the British, something to the effect that our country and its ideals were worth fighting for. I found the statue outside the dorm he lived in while at Yale. Nathan Hale, Class of 1773. He was a recent college grad, just as I was once, excited to embark on the new adventure of his life. Does anyone’s life turn out as he or she had planned? Would that all of us could meet disappointment with such grace.

New Haven really is a mecca for fans and students of the Revolutionary War. Trains make it easily accessible from Boston down to DC, and while the experience I had was priceless, all of the sites I mentioned were free. Becoming better acquainted with historic works and heroes I had studied inspired and invigorated me in a way I had not expected. Integrity and excellence brings out the best in all of us.

Disclosure: My trip to New Haven, CT, was made possible by Market New Haven, Inc. My opinions and perspectives are totally my own — as always.

Leave a Reply