The covering has the disconcerting effect of obnubilating as well as illuminating the woman behind it.

Shrouded in black niqab and ankle-length abaya, she floats towards me. Behind, her friends are firing salvos of cell-phone photos, as though we foreigners are exotic beasts in a zoo. She stops, and through her veil, in perfect English, asks, “Where are you from?”

“California.”

“What city?”

“Los Angeles.”

“What part?”

“Venice Beach. Your English is very good. Where did you learn it?

“From American movies. I watch them on my computer at home.”

“What’s your favorite American movie?

“The Devil Wears Prada.”

This is a scene on my first day in Saudi Arabia, and somehow seems evocative of a kingdom at a crossroads, theological tradition crashing against the rocks of modernity, a 7th century purity crossing swords with 21st-century internet use, and it is utterly fascinating to be here at this moment. This seclusive culture may be as different from Western versions as can be found on the planet. Women can pilot a plane, but still can’t drive themselves to the airport. Or play team sports. Or swim at a community pool. There are no beauty contests (unless you count the Miss Camel Competition, which judges the full lips and long eye-lashes). No alcohol. No public dancing. No churches, synagogues or temples. No philosophy (all you need is Allah’s word). No Teslas. And no tourist visas. This is the hardest place for non-Muslim travelers to visit in the world. I spent 16 years, and 1000 cups of tea, trying to set foot here. It is worth the wait.

Approaching Riyadh from the air at midnight the desert out the window looks like an ocean of ink. And the capital, largest city in the Kingdom, zaps the darkness like an island Oz.

After a short night we begin our tour with a visit to the state-of-the-art National Museum, which explores the epochs of the peninsula from the dinosaurs through the pre-Islamic period of waywardness, to Mohammed’s revelation and the Muslim conquests, to King Abdul Aziz’s stitching together of the tribes to create the current Kingdom, to development since the discovery of black gold, the high-grade crude that paid for these galleries.

Our erudite guide, Ali, as colorful as any exhibit, challenges the Saudi code of humility and reticence. In his flowing white thobe he has a dash of Omar Sharif about him, and confesses his goal is to marry a rich, old American.

Then we head over to Diriyah, a sunbaked complex of mud-brick houses, ramparts, grassy parks, and cafes, that has the feel of a Phoenix mall.

It is Friday, the day of rest in Arabia, and the lawns are filled with family picnickers sprawled beneath the shade of date palms. This respite alongside the shaded Wadi Hanifah is the birthplace of Wahhabism, the rigid doctrine that radiated outwards and rocked the Arabian Peninsula, laying the foundations for the House of Saud. But here, now, everyone carries a cell phone, and most are using Snapchat (with images and messages conveniently vanishing) and WhatsApp and Twitter, and kids with ice-cream cones are riding hover-boards through the snaking alleys. Sixty per cent of Saudis are under twenty, and most are as connected as a Silicon Valley teen. At the Jarir Bookstore, next to the Holy Koran, and between picture books of Arabia, is “How to Get Your Own Way: Who’s Manipulating You?”

In the golden light of late afternoon, we take pictures of the old mud settlement, Turaif, a UNESCO World Heritage site across the dry riverbed. Then we duck into a restaurant just before prayer call, when, in accordance with the law, doors are locked for half an hour. We take off our shoes, and sit cross-legged for a late lunch of Najdi-style cuisine, including the national dish, lamb kosha, served on a bed of long-grain basmati rice, which I wash down with a non-alcoholic Moussy Beer. As a waiter pours coffee from a beaked spout three feet above the small handleless cups, a group of young women in abayas drifts in to take our pictures. Two scramble over to my side, and whisper through gauzy black silk, “I love you,” as their friends giggle and snap and post away.

We take the night at the Radisson Blu, where “Stormin’ Norman” Schwarzkopf based during The First Gulf War, overseeing Operation Desert Storm. It looks like any major chain hotel in the world, except there is no bar in the lobby, no disco on the top floor, and there is a prayer rug in a drawer in my room. There is also an arrow pointing towards Mecca.

In the fresh heat of morning we head to the center of the city, to Fort Masmak, looking like a movie set façade. Surrounded by sand, this squat fortification was built around 1865 and was the site of Ibn Saud’s fabled 1902 raid, during which a spear was hurled at the main entrance door with such force that the head still lodges in the doorway.

Outside the fort we pass a large public space ringed with palms, formally called Deera Square, but which Ali calls Justice Square, and which ex-pats chillingly call Chop Chop Square, for reasons easily imagined.

Then it’s some shopping in the Souq Al Thumairi, which smells of oud, the dark resinous heartwood that perfumes the stalls between the carpets, copper pots, sandals, silver daggers and bling-bling.

I bargain for prayer beads; some of the women in our group haggle for Red Carpet-worthy abayas; and Brid, our tour leader who lived in the Kingdom for many years and knows quality, buys a box of gourmet Bateel dates. We all feel richer for spending our riyals.

Later we head to the airport (the only I have seen where men and women enjoy separate security lines), and board a Flynas flight to Ar Rub’ Al Khali, the great sand sea of The Empty Quarter. As the Airbus A330 takes off, a James Earl Jones-timbered voice recites a prayer for safe travel through the on-board screens.

When we land, the American women in our group change from the shapeless abayas into form-fitting safari wear. We’re met by a fleet of Toyota Land Cruisers, and take off, south of nothing, west of nowhere. The lead driver is named Metab, which means “The Exhauster,” a hold-over when tough names were adopted to scare off invaders. His long white thobe is immaculate, his black agal headband perfectly in place, but, he seems to live up to his name, veering off the road at high speed, lashing in the dark towards the void. How does he know where he is going? He has no GPS; no maps; there is no cell service; there are no tire tracks. He steers his wheel like a captain in a storm. Then, at last, a spot of light burns a hole in the darkness, and we come upon our camp, a simple goat-hair Bedouin tent in the crook of a dune with a campfire out front. Scattered around are individual zip-up Mabeet tents (Mabeet is the 12th night of the Hajj) for each member of our party, to keep out the snakes, scorpions, camel spiders and sand from the persistent wind.

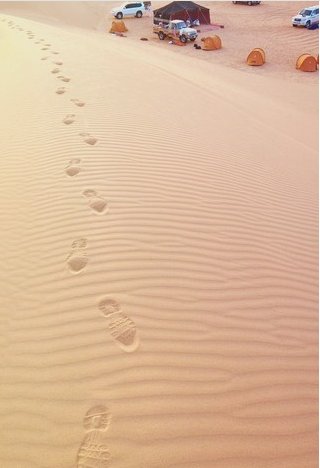

There are no showers or toilets here…this is camping as the Bedouins have always done, and with the early light I climb a rusty dune for morning ablutions. My footfalls send cascades of sand down the steep sides with the fluidity of water. Once over the crest, there is nothing but an infinite horizon, and a blessed moment of privacy.

After a breakfast of sticky dates, flat masali bread, and Laban yoghurt, the guides hand us ghutras, red and white head cloths that can protect the face from sun, wind and sand. Then they deflate the tires from 35 psi to about 11, better for traction along the roar of fine sand. Finally, in the oblique light of mid-morning, we head out into the desert, an area of vacancy the size of France, and even more hostile. Our vehicles are packed with water and spare gas (only 78 cents a gallon here, cheaper than bottled water), ready to trace the routes blazed by last century’s leathery rusticators, Wilfred Thesiger and Bertram Thomas.

We stop first at the site of The Lost City of Qaryat Al Fau, the pre-Islamic capital of the Kindah Kingdom, which prospered from the 1st century BC to the 4th century AD as a key stop on the frankincense, spice and silk routes. But, when the Romans converted to Christianity, frankincense was no longer in great demand, and the silk and spice trade was moved to the Red Sea, boats being faster, cheaper and more reliable than camels. And Quaraiyat Al Fau faded into the drifting sands. The Holy Koran has another explanation, though, for the disappearance of many of the once-great trade-route cities: “All these cities, too big with pride, we did destroy. Against some we sent a sandstorm, some were seized by a great noise. For some we cleaved open the earth, and some were drowned.”

Then we head straight into the field of dunes. Our driver, at first, flirts with the ridges and dips, the crescents and curls of sand, and then slams on the gas pedal, rockets up an unmarked crest, and flies over the top. Air Time! Grips tighten. Hearts lurch. He then plunges down the far side of the wave of fine grain, as though about to somersault, and grinds into the brown belly of a salt flat. Here he Tokyo drifts along the pan, and hurtles up another steep dune for a traverse along the face, angling the vehicle so it is on the edge of capsizing, spitting sand like a broken blender dispatching flour. Trust Allah, but buckle your seat belt.

At the crown of one dune, the drivers halt so we can step out and feel the hot breath of the desert. The dunes smoke; the wind makes a scratchy drumming sound, caused by the piezoelectric properties of crystalline quartz, the same way a needle on a phonograph translates vibrations into sound. The dunes seem to be shifting, migrating. We are in the heart of what Thesiger called “this cruel land.”

Though hired by the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit to search out locust breeding grounds, Thesiger pursued a personal quest across the desert, a quest intimately related to the nomads with whom he lived: he hoped to “find peace that comes from solitude, and among the Bedouin, comradeship in a hostile world.” The spirit of the Bedouin, he wrote, “lit the desert like a flame.” He at first felt like “an uncouth and inarticulate barbarian, an intruder from a shoddy and materialistic world.” After five years in the desert Thesiger emerged hardened by heat and thirst, and for the rest of his life (he died in 2003) he felt himself a stranger in ‘civilized’ company. He had found what he was looking for in the desert, and it had transformed him.

Back in the car for another rumble, fishtailing over the poured geometry of silvery drifts, surfing the backside of others, Metab cuts the wheel hard to the left to avoid rolling. He continues carving tracks in the loose sand, until the landscape resembles the whorls of gigantic fingertips.

As the dunes turn rose-red, tea is served. Camels shuffle by. The Arabic language contains over 1000 words to describe camels and their various breeds and states of maturity. The Bedouin call the desert sahel, “ocean,” and camels are the ships of this desert.

Midday the world takes on a pale, sun-sucked color, shadowless and uniform. It is as though Nature has exhausted every tint in her paint box. We come across a group of camel herders relaxing in the shade of a Land Cruiser, and in the Bedouin custom of unconditional hospitality, they invite us to sit and share some frothy camel milk. They are six brothers, plus a 22-year-old Sudanese contractor, who stares big-eyed at the women in our group. When asked, he says he hasn’t seen a woman in 18 months.

“Do you get any news from beyond the Empty Quarter?” I probe.

“No,” he shakes his head, after Metab translates.

“Have you heard of Donald Trump?”

“No.”

Our group applauds. At last, an outpost beyond the reach of Western media.

We camp in the sand again, but with dots of yellow spotting the landscape. They are desert lemons, which look tasty, but Metab warns not to touch, a commandment not to be disobeyed, as exposure causes diarrhea. One of our group picks up some yummy-looking nuts, and asks if they are edible. “Camel dung,” Metab grins through expressive eyes. A vulture circles overhead. Rain clouds gather, and the wind picks up.

The storm hits in the middle of the night, rippling the tents like flags, lashing the fabric with fat raindrops. But, with the dawn, the sky has been scrubbed free of clouds, and the sun is glancing over the dunes. Everything wet is dry in minutes. Breakfast is khader (maize, milk and sugar), mixed generously with blown sand.

After striking camp we ride a landscape more sky than soil, as the light changes the sand from beige to pumpkin to scarlet, and the shadows form ever-shifting patterns and textures, akin to abstract art. The high dunes, or urgs, are migratory, like the nomads they host. They are crescent-shaped with gentle windward slopes, up which the grains slowly creep and settle. They have steep leeward faces, down which grainy avalanches sometimes cascade. The dunes multiply into ever-more dense colonies, and eventually link to form sculptured chains perpendicular to the prevailing winds.

In the soft blue light of our last afternoon in The Empty Quarter the terrain turns pointillist, to flat lakebeds flagged with sharp, dark stones. All around mountains loom like dry bones through the thin air. After journeying some 800 kilometers, we stop at an oasis with a tank-like watering hole, into which all the drivers immediately plunge, fully clothed. We follow suit, swimming with Saudis in the largest sand desert in the world.

We take a late lunch of peanut butter and hummus on hard rusk at a wadi, dappled with water from the recent rain. In the slanting light the pools sparkle like jewels in a necklace…this could be Sindbad’s Valley of the Diamonds. I find a bleached camel hipbone just a few feet from a pool…he almost made it.

We begin the long drive back, from the gritty badlands to post-modern Riyadh. Once we hit pavement, there are camel crossing signs; sandstorm warnings; petro pipelines, and gaudy gas stations lit like Vegas casinos. We stop at one, and inside I can’t resist buying a bag of Lebnah and mint potato chips, as tasty as it sounds.

In the city of Al Kharj, second largest oasis in The Kingdom, we stop to overlook one of the huge ancient water wells (now mostly dry from over-tapping the water table), and then motor by the massive King Abdulaziz Palace, built by the Bin Laden family. The heat is like a wall here, until we steer into a private resort behind iron gates which sports freshly mowed grass, waterscaping with artificial cascades, cool vapor misting from shade umbrellas, and, inside, air conditioning, cold sodas and a farraginous assortment of foods.

Just outside of town we head out on a quest to find Mukabir Farzan, a field of some 500 tumulus tombs, built before the Pyramids of Egypt. But we can’t locate them. I try Google Maps; MapQuest, Waze, even Siri, but nothing. At last, behind a rough fence and up a hillside, we come across the unexcavated, unprotected, unmarked necropolis. Nobody is here but us, and the mud pie-like mounds are all empty, long-ago looted for gold and treasure. It seems we are looking into wells of unknowable time and dimension. Here men wandered thousands of years ago, origins and ends untold. The dead lie thicker than the living on this hill.

Back in Riyadh we inch through heavy traffic, past dazzling mosques, minarets, Pizza Hut, McDonalds, and a Starbucks.

before pulling into Prince Al-Waleed’s Kingdom Centre Tower, tallest in the city. It’s also known as the Bottle Opener Building for reasons evident from the street. We ride the escalator to its sleek shopping center, where on the fourth floor the most popular stores seem to be Victoria’s Secret and La Senza Lingerie (featuring “Trendy Panties, 7 for 119 Riyals”).

At the skybridge, a glassed inverted parabolic arch on the 41st floor, the city below looks aflame with flashing colors and the vectors of the future. A sign in English reads; “In case of Emergency Allah Forbidden: Do not use the elevator; Do not crowd; Do not panic.”

After breakfast we are in the airport concourse when a man wearing sandals, wrapped in white towels, with one shoulder exposed, walks past. Not the sort of attire I would expect in a modern airport. He is, Brid shares, a man on umrah, a pilgrimage to Mecca that can take place any time of year, as opposed to the scheduled and more expensive Hajj, largest religious gathering in the world.

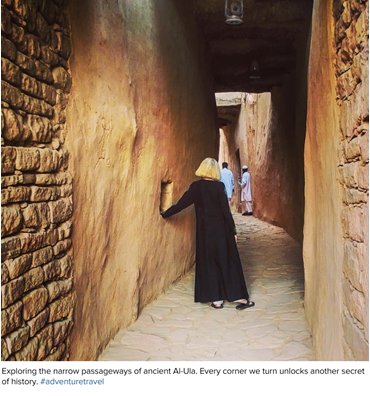

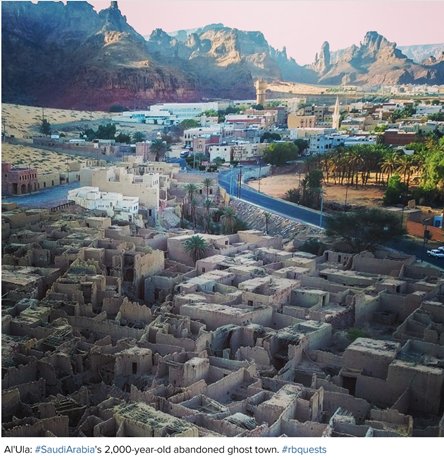

We fly north to the oasis town of Al Ula, about 450 kilometers from Jordan’s Aqaba, and a key staging area for T.E. Lawrence’s campaigns. After exploring the walled ruins of old Al Ula, once a robust stop on the caravan route between Oman and Rome, we make our way to our accommodations at Madakhil Camp, a solar-powered luxury glamp, in the high-end-safari style pioneered and perfected in East Africa.

Enveloped by the high-sandstone cliffs of Al-Hajar, the tents are decorated with simple Arabic motifs; soft, indulgent beds with Arabian horse-hair blankets; electric lights and outlets; and a jeweled chest with a prayer rug inside, in case a guest left his at home. Camels roam around outside, the canyon walls turn gold in the twilight hour, and are painted by klieg lights after dark.

There are two long common-area tents flooded with deeply napped carpets, one where cups of tea and dishes of sugary dates are served, and the other where breakfast and dinner are taken, the latter, in our visit, including a mandi, in which chicken, lamb and vegetables are baked in a sand-covered oven for eight hours before serving on the long, low table. When walking back to my tent after the savory repast, I look up and realize this is a million-star retreat.

But it’s the location that makes this stay extraordinary. It is just a few minutes from the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site at Madain Saleh, a sprawl of 140 monumental tombs spread over 15 kilometers, as magnificent and mystifying as anything on earth. They are reminiscent of Petra in Jordan, which makes sense as they were connected to the same Nabatean empire of around 2000 years ago. Imagine Petra without the tourist hordes, camel rides, and artifact mongers, but instead the relics of a vanished civilization set in a surfeit of buttes, mesas, spires, slot canyons and phantasmagoric formations that make Monument Valley look like facial pimples, and you have a picture of what this place offers.

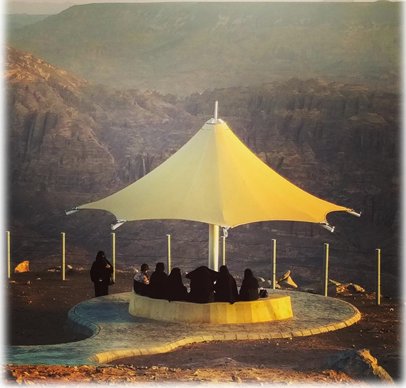

We make a steep switchback drive to the top of the escarpment, to the Haratawerth Overlook, where groups of Saudi women, like crows on a wire, are enjoying a view quite similar to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

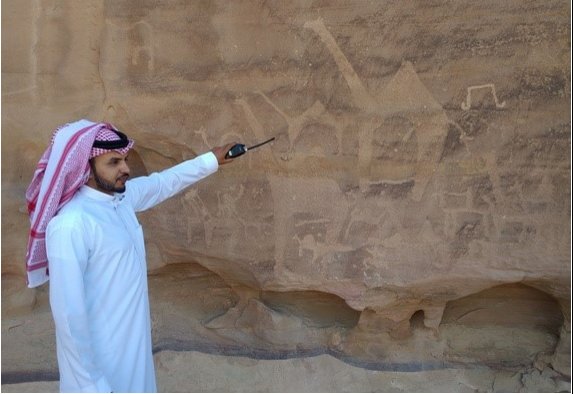

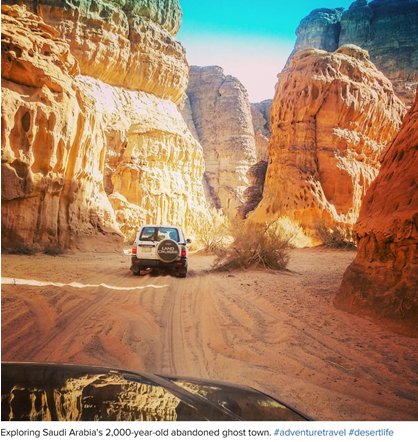

Then we do some more dune-bashing with Yusuf as our driver. I feel safe as he has a pendant hanging from his rearview mirror that features 99 names for God (he says his mother gave it to him for luck and safety when he did the Hajj). Yusuf trundles up Ragasat Canyon, past a jumble of rock pillars called the Dancing Ladies, into sinuous passageways beneath curved cliffs and ancient rock art.

We stop for tea in the shade of a mushroom-shaped rock of pink sandstone topped with the red stains of iron ore deposits, and then caterwaul some more through the ungentle dunes.

Evening is the best time to view the tombs of Madain Salih, carved in the sides of the smooth, rounded red-stone formations that dot the desert floor. They are all impressive, and we can walk into the empty chambers of many, some with slots carved into the walls to shelter the bodies of a family.

On the exterior pediments the heads of eagles have been cut off, and there are bullet holes around the carved roses and snakes, defacements by devout sects that believe any icons are forbidden by strict interpretation of Islam. We duck into a large room carved from the rock, a Diwan, a religious gathering place where animals were sacrificed; and we can trace a complex viaduct system that runs along the outside walls. The Nabateans were master hydro-engineers, manipulating rain run-off and aquifers to allow human flowering in the desert.

The most imposing of the tombs is Qasr Al Farid, carved from a single sandstone monolith, from the top down, which we explore without another traveler in sight, as though we are with Charles Doughty, the British explorer who came across this treasure in 1876.

Opening the tent flap the final morning, the sunlight filters through the canyon, bringing colored life to the cliffs and sand. We head out to tour one of the stations on the Hijaz Railway line, opened in 1908. The narrow gauge linked Damascus to Medina, designed to carry pilgrims on Hajj, cutting travel time from six weeks to four days. Station forts were built every 25 kilometers along the 1300 kilometer route to protect the railway from bandits. During the first World War the Ottomans sided with the Germans, while T.E. Lawrence helped orchestrate the Arab Revolt, blowing up trains and tracks.

Image

The railway closed in 1918, and never ran again.

From here we drive three hours north, with a police escort, to Tabuk, home to the Kingdom’s largest air force base. We’re behind schedule, but Yusuf never exceeds the speed limit, as speeding tickets are assessed directly to the car owner’s cell phone, and if not paid, the government blocks the phone, an effective incentive. But we make it in time for a quick dinner, some Saudi Champagne (apple juice and Perrier) to toast our trip, and catch the last flight back to Riyadh. Then we each board our connecting flights to the U.S., to a world even Sinbad could not have imagined, leaving behind, however faint, the imprint of Saudi Arabia, and its sophrosyne grace of custom, belief and hospitality.

Presently there is only one adventure travel company in the world offering tours to Saudi Arabia, Mountain Travel Sobek. Contact tanya@mtsobek.com for details

Excellent article, Richard. Fantastic videos & pics. Thanks for the tour.

M & G

NYC

After reading this, Saudi Arabia is def on my list to visit – I just read an article saying they may start opening up the country a bit more for tourists – that would be quite helpful

Nice article, but a bit hard on the women there, aren’t they?

That’s interest they call the sand dunes the ocean. I am sure they were once.

Anyway, lot’s of incongruous images in this essay that really make one get a sense of what it’s like to be there.