John M. Edwards grabs his “Beachcombers Card” and does Divali (Festival of Lights) on delicious Mauritius, a paradisiacal Indian Ocean isle–once the roost of extinct dodos, now the boast of professional beachbums–which initially he can’t place on a map!

John M. Edwards grabs his “Beachcombers Card” and does Divali (Festival of Lights) on delicious Mauritius, a paradisiacal Indian Ocean isle–once the roost of extinct dodos, now the boast of professional beachbums–which initially he can’t place on a map!

“Incredible!” You are from New York?!” boomed Willy Van Damme, a friendly Belgian restaurateur and former soldier of fortune, in the sleepy resort town of Péreybere. “Very rare! We get almost no Americans, only French, South Africans, some Germans, English, and the odd Italian.” At a snap of Willy’s fingers, an Indian waiter with a smart Nehru jacket and an ingratiating smile darted over and poured my Phoenix beer. Sitar music twanged mystically in the background. With a cavalier wave of the hand, Willy added, “Perhaps then you’ve heard of my half brother?” A dramatic pause followed. “Mr. Jean-Claude Van Damme!”

What was this place? I wondered. Bollywood?

In Following the Equator (1897), Mark Twain wrote, “You gather the idea that Mauritius was made first, and then Heaven; and that Heaven was copied after Mauritius.” If so then the blueprints for paradise lie east of Eden, west of Waikiki, and about 500 miles off the coast of Madagascar—on a harmonious multiethnic “paradise lost” most Americans can’t even find on a map.

One of the most densely populated areas in the world but with the highest standard of living in “Africa,” the 720-square-mile reef-fringed island in the Indian Ocean hosts a beatific bevy of beaches and a cultural curry of Indians, Chinese, Africans, Europeans, and Creoles. Despite a Babel of imported tongues, English is the official language (sort of), while the everyday lingua franca is Mauricyen (a patois of French Creole similar to Haitian).

When I first arrived at the airport with a heartflutter and a thwump on an Airbus owned by Air Mauritius, I thought I’d landed in one gigantic sugarcane plantation: a fantastical dreamscape resembling the old boardgame “Candy Land!” ™ But the memories inspired by sugar on delicious Mauritius are more bitter than sweet.

Mauritius (“Maurice” in French) was known to 10th-century Arab traders as “Dinarobin.” They spun Sinbad legends about the island’s tasty Dodos to sailors and stevedores in Tintin comic ports worldwide, before the arrival of the Portugeuse (1510), Dutch (1598), French (1715), and British (1810), who all turned the now extinct bird into the local equivalent of KFC. In 1968, the Mauritian “Gandhi,” Sir Seewoosagar Ramgoolam, helped Mauritius gain its independence.

Mauritius (“Maurice” in French) was known to 10th-century Arab traders as “Dinarobin.” They spun Sinbad legends about the island’s tasty Dodos to sailors and stevedores in Tintin comic ports worldwide, before the arrival of the Portugeuse (1510), Dutch (1598), French (1715), and British (1810), who all turned the now extinct bird into the local equivalent of KFC. In 1968, the Mauritian “Gandhi,” Sir Seewoosagar Ramgoolam, helped Mauritius gain its independence.

It was the Dutch who named the island for their Prince Maurice of Nassau. It was also they who introduced the sugarcane that covers 90 percent of arable land. Nowadays, sugar is one of the country’s leading exports, with manufacturing and tourism rounding out the economy. (As a sweet-toothed legacy, a local musical tradition called “Sega” drives home its reggae-like vibe.)

After the abolition of slavery in 1835, conscript laborers from India arrived, and today they make up nearly two-thirds of the population of a little over a million. Periodically I’d bus past cairns of lava boulders looking like mini Mayan pyramids and interrupting the cane fields—testimony to the backbreaking labor responsible for clearing the plantations. (Cane is still machete-hacked here by hand.)

On upside-down Technicolor Mauritius, deciding on digs is at best spectator sport. Where would I stay? There was the ultra-exclusive resort Le Touessrok, whose architect Maurice Giraud succeeded in building his “Playground of the Gods”—a safe haven for the affluent, way out of view of the hoi polloi. Hey, isn’t that Liz Hurley? It was built complete with a mock Bridge of Sighs, Venetian-style footbridges, and its own private isle. Across from Le Touessrok, the idyllic Ile aux Cerfs (Island of the Deer) offered herds of wild Java deer and deserted coves ideal for nude sunbathing.

Strapped for cash, though, I found the budget mecca of Péyrebere to be a good runner-up.

Here at this idyllic resort town, I met a traveler in an antique land:

“Sue, look, I think that is Rolf Potts going native!”

In front of us on a hillock, there was this serious dude wearing an orange robe with a swastika charcoaled on his forehead. He looked pleasant enough, just standing there with his fabulously impressive trident.

Sue did her legendary laugh: “Eeee!”

After we sailed a friendly greeting, the traveler took off his robe and hunched up his shoulders, open-mouthed, signifying he didn’t quite get it. He then munched on a roti, acquired from a roaming Snacky Cart vendor.

Wait a triple sec, this obviously wealthy hipcat traveler might in fact be a local who did not speak any English at all, a product of either the Aryan Conquest of the Subcontinent or the progeny of the British Raj.

Scary enough, pals, for those of you who equate surprising world culture clashes with suffering through “Les Miz,” then raiding the salad bar at Appelbee’s.

Maybe this Brahmin lad, a real live Sadhu in a diaper loincloth lollygagging on the beach, spoke only Sanskrit?

In the lazy days that followed, I avoided the persistent taxi mafia and bused it all over the island (the best and cheapest way to get around), taking in the white sand beaches, amber waves of cane, and mocha-colored mountains.

Most nights I hung out at Péyrebere’s popular Indian bar, where a band of dreadlocked Hindus played Michael Jackson and UB40 covers note for note:

“I’m an alien, I’m an illegal alien, I’m an Englishman from New York!”

Were they singing about me? I was the only person there wearing a Yankees cap.

Here Ranjan, a deep-sea fisherman, told me of the upcoming holiday of Divali (Festival of Lights). “You will enjoy Divali. Don’t miss it.” Added an expatriate Brit married to a local Tamil woman, “Mauritius is unique: People of different religions celebrate each other’s holidays.”

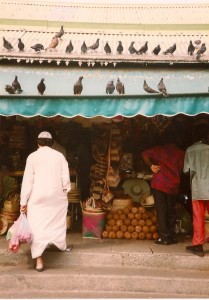

I learned about “sights” in the capital of Port Louis—a President Kennedy Street, a Nelson Mandela Boulevard, and a Muammar Khadafy Square. No joke. Later at Port Louis’s DSL (Deva Saraswatee Laxmi ) Coffee House, opposite the St. Louis Cathedral, I listened to a ululating muezzin from the nearby Jummah Mosque, right in the middle of Chinatown. Whoah! Mauritius might very well be, as the Mauritian tourist bureau keenly advertises, “The most cosmopolitan island in the sun!”

“You are here for ze deep-sea feeshing?” queried Grenouille (Frog), a monied French drifter from nearby Réunion, with a surprising self-proclaimed moniker, who was staying at my guesthouse. He said he was involved in “animation,” which he couldn’t translate from the French. Perhaps, this was just a euphemism for “unemployment.”

Frog suggested we take an unofficial tour with local fisherman to one of the deserted islands. His enthusiasm was catching. “We make a party! We make a party!” Frog repeated like a Grand Siecle chanson.

Just beyond the coral reefs, the waters teemed with blue, black, and striped marlin; yellow-fin and skipjack tuna; sailfish; barracudas; sharks; dorado; and what have you. A virtual waterworld, Mauritius yet only reels in a couple thousand American tourists a year. Up everywhere were signs for “Deep Sea Safaris” and “Big Game Fishing.” With all that, Grenouille wondered why an American had come so far—to not catch fish?

But I was there to eat them.

In fact, fish schools caught in semicolon nets aside, Mauritian cuisine is as mixed as its people. One night at the inexpensive Café Péyrebere, evocative of a mini dim sum palace, I tried something a little different. Perusing the menu for specialities such as smoked marlin, curried cerf (stag), and couer de palmiste (a.k.a. “millionaire’s salad,” made from the heart of a 7-year-old palm), I placed my order. The poker-faced Chinese waiter informed me, “Sorry, we are out of lobster. But we make you something extra special!” He cracked a smile. “Okay, you try!”

An hour later and still no dinner, I asked what exactly was this “special” dish?

“SACRE CHIEN!” The waiter beamed. I began to grow a little queasy. This, of course, is French for “sacred dog.” An adventurous eater, I still wasn’t sure I could dig into a poached pooch. Needless to say, as the waiter removed the dome with a flourish, I was very relieved when the dish turned out to be not a steaming baked Airedale or grilled Golden Retriever, but just a kind of fish. The joke was on me—as it has been on many an unsuspecting customer before, I imagine.

Correct, now it is time to check out the island’s stunning sand traps. One morning after my habitual café au lait and flakey croissant, the sun sent out an open invitation, and I answered the call. In Mauritius you never have to go far: beaches are everywhere. “Very good bitch!” the “snacky cart” (street food) vendor enthused, handing me a rolled aloo paratha and pointing across Péyrebere’s one main road: the Route Royale, lined with low-key restaurants, bars, and guest houses.

Before me was a virtual-reality paradise, mirrored in my Oliver Peoples sunglasses—two of the island’s best swimming beaches right in the center of town, one of which was marked “private.” By law, all beaches from the high tide to the low tide marks are public property. So ignoring all the “Acces Interdit” (No Trespassing) and “Chien Dangereux” (Dangerous Dog) signs outside the seaside villas, I set up my loud sarong on the powdery white sand of the “plage privée” (private beach). The strand was nearly deserted, except for a topless sunbathing woman. . . .

After a solid week of beachcombing and now bronzed as a Buddha, I hiked around the coast, passing small dhows bobbing like Champagne corks in the water, until I arrived at Cap Malheureux (Cape of Misfortune), the northernmost point where the Brits first landed. I plopped down and gazed out to sea. In the Impressionistic light, nearby Coin de Mire, a humpback-whale-shaped island, seemed to be swimming ashore. Farther out lay Flat Island (not flat), Round Island (not round), and Serpent Island (no snakes).

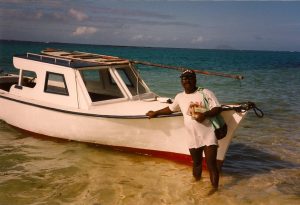

The sea beckoned—literally. For the idyll was broken by a small unseaworthy-looking vessel, an independent deep-sea fishing boat plying the waters for customers. It anchored, unloading a pair of disgruntled sunburnt Afrikaners arguing in their queer-sounding argot, followed by their wily skipper—a Mauritian Love Boat

“Captain Steubing” in too-tight Speedo briefs. He jogged over with a gigantic book under one arm.

“You come with me to flat Island!” he encouraged—no, demanded—turning the pages of unfocused pictures of previous customers looking miserable on a Conrad-style tropical isle of some sort. “Very cheaps. We catch fish. We eat fish.” Smiling like a Cheshire Cat—no, a Blue Meanie—he tried the hard sell. Caught in the vise-like grip of the sun, I politely declined: “No thanks, I don’t fish.”

At last he shook my hand and motored off. But already I had regrets. I had missed my chance at a guaranteed misadventure. I couldn’t help but think he had popped back into the pages of an unpublished Kipling novel.

After days on end of milling around and meeting locals, my attention turned to the buzz of excitement building on the island.

Aha! Divali Day dawned!

I took an informal tour with the dour Monsieur Fan Fan and Ebrahim Tours. After the driver stopped in town to lengthily pick up a “beef paté baguette,” thus marking himself as a non-Hindu, we set off for the main “attractions.” First off was the 60-acre Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Gardens in the funnily named town of Pamplemousses (Grapefruits). In this transplanted Eden, in 1768, Pierre Poivre (Peter Pepper—seriously!) began to collect indigenous plants such as mahogany, ebony, lantania, and pandanus, in addition to the ubiquitous palms.

Next on the tour was the much-touted “Trou aux Cerfs” extinct volcano crater, looking like a reality-scarred postcard of Rama’s gigantic coffee mug, followed by Mauritius’s number-one tourist attraction: the “Chamarel Colored Earths”—a mountain of multicolored mud straight out of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic Dune.

Finally we arrived at the sacred Hindu site of Grand Bassin (Great Pond), a 66-foot-deep volcanic crater lake. Inside the onsite temple, Hindu worshipers in full regalia chanted; lit earthenware lamps to a plethora of elephant-trunked and multi-limbed gods; and made offerings to, among others, Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. They serenely smiled. Nobody seemed to mind that we had dropped by.

Wandering outside, I spotted a sari-clad Hindu woman and her daughter, splashing through the holy waters, which according to legend come from an underground stream directly linked to the Ganges. I stuck a tentative finger in the lake. Why not? Soon I was up to my knees in water.

Later on as the evening set in, my erratic thoughts turned to genuine anticipation. Under a sky darkened like a stretched- out athletic sock, the celebrations began. So I headed out with Grenouille and a group of travelers to the epicenter of activity: the Hindu village of Triolet.

Like a bewildering mixture of Christmas, New Year’s, Fourth of July, and Halloween, the mini-“Mardi Gras”-like Divali celebrates the victory of Rama over Ravana and Krishna’s destruction of the demon Narakasuran.

And some.

As our nondescript spy van inched through the traffic, we stared out at Mauritian homes bedecked with Happy Holidays lights, oil-burning clay lamps, and ruffled paper lanterns—homeowners trying to keep up with the Gandhis by spending thousands of rupees on ostentatious displays.

Fireworks popped and sizzled.

From loudspeakers, tinny nasal spiritual songs crackled.

In the crush of so much humanity, the van halted.

A grinning Ahab-bearded man wearing a black eyepatch, kurta pyjamas, and a haji cap, vaguely resembling Pico Iyer dressed as a Barbary Coast pirate, threw a roll of firecrackers onto the windshield.

Ultimately, in the headlight beams we saw a father and son holding hands, while the kid swung, of all things, a gourd jack-o’-lantern with an evil grin.

Hence, the car horns chirped in the darkness like evil mechanical cicadas. We weren’t going anywhere. I’d come all the way to the other side of the unknowable world not only to not catch any fish at all, but to get stuck in a gnarly traffic jam. Nevertheless, the fun festivities of Divali, the island’s primitive beauty,

and the wonderful tumble of cultures held me fascinated.

Summing up the scene, two French Huguenot tourists sitting next to me could barely restrain their excitement, snapping scenes with their fancy digital Elf cameras.

“Sauvage!”

“Sauvage!”

“Egoist!!!” I added.

There were worse places to be stuck.

Leave a Reply