After my divorce, I needed to travel, to go on a journey to find myself. What better place to start than Ireland, home of my ancestors? During my trip I found images and parts of me that I didn’t know existed. I found them in the faces and personalities all around me; in their laughter and ability to laugh at themselves; in the scenery; the castles and cottages; in the weather- stormy and changeable like myself; in the roads: driving on the “wrong side of the road”, (the story of my life); in their music and dancing that made me feel alive and proud to be Irish; in their passion for independence and self expression in any form; and in their stories of heroes and villains, sinners and saints-all that is within me. It was like going HOME after a long, long absence. It was like coming home to myself.

After my divorce, I needed to travel, to go on a journey to find myself. What better place to start than Ireland, home of my ancestors? During my trip I found images and parts of me that I didn’t know existed. I found them in the faces and personalities all around me; in their laughter and ability to laugh at themselves; in the scenery; the castles and cottages; in the weather- stormy and changeable like myself; in the roads: driving on the “wrong side of the road”, (the story of my life); in their music and dancing that made me feel alive and proud to be Irish; in their passion for independence and self expression in any form; and in their stories of heroes and villains, sinners and saints-all that is within me. It was like going HOME after a long, long absence. It was like coming home to myself.

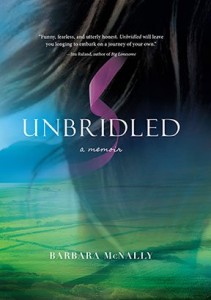

Excerpt from Unbridled: A Memoir

“In Cathair na Mart, the Carrowbeg River runs through the center of town,” my grandmother Pat told me, “with tree-lined promenades on either side.

The streets have simple names like Bridge and Shop.”

Crossing the river on Bridge Street, I found the Heritage Centre, a nineteenth-century stone building not much bigger than a truck, the walls hung with sepia photos from the 1800’s depicting the era of the Potato Famine.

“Can I help you?”

“I’m here to find my family.”

I learned about several genealogy services and chose one that would trace my family’s history in the region.

With the kind woman staffing the Centre, I went over notes with names and places I believed were tied to my family history as well as the few photos I’d brought. She began to fill out a chart for me based on what she’d found in the files and promised to do more research.

“There’s a McNally that runs a bed-and-breakfast here in town. Some of your people probably lived there before they emigrated to America.”

The McNally B&B was a two-hundred-year-old structure whose thatched roof protected it from western Ireland’s persistent coastal rain.

“Welcome, me name’s Connor McNally.” The proprietor’s brown curls spilled out from under his tweed cap.

“I’m a McNally, too. Barbara. From California.”

“‘Course,” he said.

A fire roared in the open fireplace, and pots and pans hung from pegs on the wall. Everything was so neat and tidy I hardly noticed the floor was packed dirt. I imagined my ancestors sitting in that very spot, their feet touching the same ground. It was a dizzying thought. Aside from the occasional pop from the fireplace, the cottage was quiet, insulated from the sounds outside by its thick walls and a warm, floury smell drifted from the stove.

“I’d love some. I’m famished.” Immediately, I regretted my choice of words. “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be,” he said. “An Gorta Mór-the Great Famine-is more than a memory in this part of the country. It’s always with us. If ya’re interested, there’s a memorial up the road.”

He reached for the chart I’d received.

“Ah, yes. There are still plenty of us McNallys, roaming around these parts. Our name means ‘poor.’ The clan is known as Black Irish because the native Irish mixed with Spanish survivors of the armada that wrecked off the coast of Westport.”

“One woman in your bloodline is legendary-Grace O’Malley. Have you heard of her? She has quite a history here.”

“Oh, my gosh. My Grandma Pat used to tell me stories about her.”

I devoured more griddle bread, washing it down with hot tea, as Connor told me about Gráinne Ní Mháille, the Pirate Queen. Grace was a strong-willed woman who lived in the area during the sixteenth century. Her family came from Clare Island, just off the coast of Westport, and she used it as a base of operations for her seafaring adventures. She attacked ships at sea and fortresses on the coast and was admired by men and women alike for her savvy techniques as a leader of fighting men, a real coup for a woman. Married several times to prominent figures, Grace accumulated a great deal of wealth, through her escapades and her inheritances. Grandma Pat had looked up to her as a woman ahead of her time. A heroic warrior.

“My Grandma always described her as fearless.”

Connor nodded. “She lived during a period of social change and political upheaval. From what I know, she ignored all the rules as to how a woman was supposed to act and became one of Ireland’s foremost feminists.”

“There is a statue of her near Westport House, a historic home not far from here.”

I rolled up my pants, threw a leg over the bicycle Connor offered and started pedaling down the lane toward the Octagon-a loop of pubs and shops in the center of town near the massive statue of Saint Patrick. I made my way west, around the bay, and toward Croagh Patrick mountain, which cast a shadow cast over Westport.

In the soft mist that hung over the inlets and water ways, I passed Celtic crosses fields full of sheep, their shaggy coats heavy with moisture. I came to a sign for the National Famine Memorial and made the turn. As I approached the memorial, a bronze ship becalmed in a sea of concrete, I let out a startled gasp. What I first thought were tattered sails hanging from the masts were instead haunting representations of the dead, twisted in the rigging. Hollow skulls and outstretched bones, skeletons aboard the ship bore tribute to those who had suffered and died or emigrated during the Great Famine. I wondered what I would have done if I’d been in their situation. Would I have had the courage to leave? To stare down death and disease and make a new life for myself in a country I didn’t know? No car. No grocery store. No credit cards.

In the soft mist that hung over the inlets and water ways, I passed Celtic crosses fields full of sheep, their shaggy coats heavy with moisture. I came to a sign for the National Famine Memorial and made the turn. As I approached the memorial, a bronze ship becalmed in a sea of concrete, I let out a startled gasp. What I first thought were tattered sails hanging from the masts were instead haunting representations of the dead, twisted in the rigging. Hollow skulls and outstretched bones, skeletons aboard the ship bore tribute to those who had suffered and died or emigrated during the Great Famine. I wondered what I would have done if I’d been in their situation. Would I have had the courage to leave? To stare down death and disease and make a new life for myself in a country I didn’t know? No car. No grocery store. No credit cards.

The thought of fellow human beings-and relatives-stuck in rank ships with conditions so poor they were called coffin ships overwhelmed me. I cried for my great-great-grandmother, Bridget. I cried for Grandma Pat. I cried for my mother. I cried for myself. I even cried for Grace, the Pirate Queen. The life of a pirate couldn’t have been easy.

I hadn’t seen the statue I’d headed out to see, but I wanted to be around people now, have hot food and a cold beer. I pedaled back to town and a busy pub. Keeping an eye on Connor’s bicycle though the window, I listened to a fiddler and a mandolin player, who sang Irish ballads. Old men sat at tables, sipping their healers. Kids darted between video games, trying to make the buttons and joysticks work without the required coins. A television screen broadcast a soccer match. My stomach rumbled with hunger after my emotional trip to the monument. I ordered a pint of Guinness and a bowl of fisherman’s stew, which arrived smelling of the sea. Grace O’Malley would have known how to help the town residents if she had been alive during the Famine. As soon as I found a postcard, I would write my mother, my sisters, and my daughters from Cathair na Mair, our ancestral home. I would tell them about the strength of the blood running through our veins.

Barbara McNally is the author of Unbridled: A Memoir and founder of the Mother Lover Fighter Sage Foundation. Proceeds from Unbridled go to the foundation whose primary focus is to assist the wives of wounded warriors.

Leave a Reply